by Eric Yarnell, ND, RH(AHG)

Last updated 18 Apr 2022

This monograph is protected by copyright and is intended only for use by health care professionals and students. You may link to this page if you are sharing it with others in health care, but may not otherwise copy, alter, or share this material in any way. By accessing this material you agree to hold the author harmless for any use of this information.Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site. Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site.

Table of Contents

Clinical Highlights

Uva ursi, greenleaf manzanita, madrone, and related species are urinary antiseptics and astringents.

These herbs are very safe but may cause nausea.

Uva ursi, greenleaf manzanita, madrone are moderately potent. Clinically madrone is the most potent, greenleaf manzanita is second, and uva ursi is mildest (but all are clinically effective if dosed properly).

These herbs are very safe but may cause nausea.

Uva ursi, greenleaf manzanita, madrone are moderately potent. Clinically madrone is the most potent, greenleaf manzanita is second, and uva ursi is mildest (but all are clinically effective if dosed properly).

Clinical Fundamentals

Part Used: the leaf, fresh or carefully dried (using moving air not heat) are used as medicine in all three species. The fruits of uva ursi and madrone were also commonly eaten as food.

Taste: astringent

Major Actions:

Intake of single dose of dry leaf uva ursi extract providing 800 mg arbutoside led to absence of bacterial growth in the urine of volunteers for 5 d (Frohne 1970). Another ex vivo study showed that urine from healthy adults given oral doses of 100–1000 mg arbutoside was bacteriostatic against Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Kedzia, et al. 1975). Activity was as strong as that of gentamicin and nalidixic acid. In vitro studies confirm that ethanolic and other extracts of uva ursi leaf are active against E. coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus vulgaris, Enterobacter aerogenes,Streptococcus faecalis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, P. aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Klebsiella spp, Shigella sonnei, and Shigella flexneri (Snowden, et al. 2014; Vučić, et al. 2013; Ng, et al. 1996; Holopainen, et al. 1988; Robertson and Howard 1987; Moskalenko 1986; Jahodár, et al. 1985). Uva ursi also reduces virulence in Listeria monocytogenes in vitro (Park 1994). A study in rats with experimental pyelonephritis found that oral dosing of 25 mg/kg uva ursi extract led to excellent antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects (Nikolaev, et al. 1996).

Uva ursi has not been studied in humans as a diuretic, as far as could be determined, though it is often cited for having this property in various herbals (Foster 1993). Uva ursi is, if anything, clinically somewhat antidiuretic due to its astringent nature. In one rat study, an infusion of uva ursi leaf (3 g/L) did not induce diuresis or aquaresis and did not alter urinary calcium or citrate concentrations (Grases, et al. 1994). Another rat study did find uva ursi leaf infusion aquaretic without altering urinary sodium or potassium levels, so it was not diuretic (Beaux, et al. 1999).

Major Organ System Affinities

Major Indications:

Note that, "Uva ursi leaf, dry extract, and fluidextract were official in the United States Pharmacopoeia and National Formulary from 1820 to 1950" (Blumenthal 2000).

Though generally uva ursi is considered primarily useful for treating acute urinary tract infections (UTIs), there is some evidence it is useful in preventing recurrent infections. One published double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of uva ursi involved 57 Swedish women with recurrent cystitis (Larsson, et al. 1993). They were randomized to take uva ursi extract (standardized to arbutoside and methylarbutoside) or placebo for one month. The uva ursi extract group had no cystitis in the following year compared to 23% of women who took placebo, a significant difference. There were no adverse effects reported Another trial, which was apparently an open design, found that Italian women with recurrent UTIs who took D-mannose with either arbutoside, berberine, Betula spp (birch) extracts, and forskolin had significantly lower rates of recurrent infections compared to those who took D-mannose combined with proanthocyanidins (Genovese, et al. 2018).

More recently, two large clinical trials have investigated the efficacy of uva ursi for treating acute UTIs. In one double-blind trial (dubbed Regatta), 398 German women with uncomplicated UTIs were randomized to either an uva ursi extract, a single 3 g dose of fosfomycin, and their respective placebos (Gágyor, et al. 2021). The uva ursi extract used contains 105 mg arbutin per tablet, and three were given twice daily for 5 days. The uva ursi group ended up taking significantly fewer courses of antibiotics than the fosfomycin group, but was associated with more symptoms. There was a non-significant trend toward a higher rate of pyelonephritis in the uva ursi group than in the fosfomycin group. The mixed results of this trial could in part be interpreted as lack of clear superiority of the uva-ursi, but also that the dosing scheme used was simply insufficient.

A similar trial (dubbed Atafuti) randomized 382 English women with uncomplicated UTIs to a different extract of uva ursi (1200 mg tid, containing 240 mg arbutoside per dose) + advice to take ibuprofen 400 mg tid if needed, placebo + the same ibuprofen advice, uva ursi without ibuprofen advice, and placebo without ibuprofen advice for 3–5 days (Moore, et al. 2019). All participants were given a back-up antibiotic prescription to take if any participant wanted to. The uva ursi extract at this dose was not superior to placebo at reducing urinary symptoms or preventing antibiotic use, though ibuprofen advice was. There were no significant adverse effects with uva ursi and no participants developed pyelonephritis. The reasons for the substantially lower efficacy in this trial compared to the Regatta trial mentioned above are difficult to fathom, other than that possibly the extract used in this trial was in some way inferior.

Given the ongoing rise of antibiotic resistance in uropathogens, such that many formerly first-line antibiotics for this infection are simply no longer effective, uva ursi and other herbal options for uncomplicated UTIs are becoming ever more crucial to assess and adopt (Yarnell 2017; Guay 2008).

Clinically, uva ursi is very helpful in patients with UTIs, with failure most often being associated with under dosing (both low doses and insufficiently frequent doses, both supported by the clinical trials discussed above). Also, It is best when uva ursi is combined with other urinary antiseptics with different chemistries and activities, and with herbs that are diuretic and inflammation modulating with a focus on the urinary tract (see the Classic Formulas section below).

Major Constituents:

The 2014 European Pharmacopoeia (version 8.1 supplement) requires a minimum of 7% arbutoside in uva ursi leaf sold as medicinal products.

Uva ursi extracts are more effective than isolated arbutoside as urinary antiseptics (Werbach and Murray 2000). This is also believed to be true for greenleaf manzanita, madrone, and related species.

Note that arbutoside is also found in significant levels in several commonly-consumed foods, including pears, wheat, red wine, coffee, tea, and broccoli (Deisinger, et al. 1996). Consumption of all of these foods were shown to increase urine hydroquinone levels in humans and, at least in the case of pears, wheat, coffee, tea, and broccoli (if tolerated by the individual patient) are recommended for consumption during acute UTIs.

Taste: astringent

Major Actions:

- Urinary antiseptic, bacteriostatic (Yarnell 2017; Tolmacheva, et al. 2014; Snowden, et al. 2014; Holopainen, et al. 1988; Kedzia, et al. 1975; Frohne 1970)

- Astringent (Yarnell 2017)

Intake of single dose of dry leaf uva ursi extract providing 800 mg arbutoside led to absence of bacterial growth in the urine of volunteers for 5 d (Frohne 1970). Another ex vivo study showed that urine from healthy adults given oral doses of 100–1000 mg arbutoside was bacteriostatic against Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Kedzia, et al. 1975). Activity was as strong as that of gentamicin and nalidixic acid. In vitro studies confirm that ethanolic and other extracts of uva ursi leaf are active against E. coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus vulgaris, Enterobacter aerogenes,Streptococcus faecalis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, P. aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Klebsiella spp, Shigella sonnei, and Shigella flexneri (Snowden, et al. 2014; Vučić, et al. 2013; Ng, et al. 1996; Holopainen, et al. 1988; Robertson and Howard 1987; Moskalenko 1986; Jahodár, et al. 1985). Uva ursi also reduces virulence in Listeria monocytogenes in vitro (Park 1994). A study in rats with experimental pyelonephritis found that oral dosing of 25 mg/kg uva ursi extract led to excellent antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects (Nikolaev, et al. 1996).

Uva ursi has not been studied in humans as a diuretic, as far as could be determined, though it is often cited for having this property in various herbals (Foster 1993). Uva ursi is, if anything, clinically somewhat antidiuretic due to its astringent nature. In one rat study, an infusion of uva ursi leaf (3 g/L) did not induce diuresis or aquaresis and did not alter urinary calcium or citrate concentrations (Grases, et al. 1994). Another rat study did find uva ursi leaf infusion aquaretic without altering urinary sodium or potassium levels, so it was not diuretic (Beaux, et al. 1999).

Major Organ System Affinities

- Urinary Tract

Major Indications:

- Urinary tract infection, lower (treatment)

- Urinary tract infection, recurrent (prevention)

- Infectious diarrhea

- Urethritis, non-gonococcal

Note that, "Uva ursi leaf, dry extract, and fluidextract were official in the United States Pharmacopoeia and National Formulary from 1820 to 1950" (Blumenthal 2000).

Though generally uva ursi is considered primarily useful for treating acute urinary tract infections (UTIs), there is some evidence it is useful in preventing recurrent infections. One published double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of uva ursi involved 57 Swedish women with recurrent cystitis (Larsson, et al. 1993). They were randomized to take uva ursi extract (standardized to arbutoside and methylarbutoside) or placebo for one month. The uva ursi extract group had no cystitis in the following year compared to 23% of women who took placebo, a significant difference. There were no adverse effects reported Another trial, which was apparently an open design, found that Italian women with recurrent UTIs who took D-mannose with either arbutoside, berberine, Betula spp (birch) extracts, and forskolin had significantly lower rates of recurrent infections compared to those who took D-mannose combined with proanthocyanidins (Genovese, et al. 2018).

More recently, two large clinical trials have investigated the efficacy of uva ursi for treating acute UTIs. In one double-blind trial (dubbed Regatta), 398 German women with uncomplicated UTIs were randomized to either an uva ursi extract, a single 3 g dose of fosfomycin, and their respective placebos (Gágyor, et al. 2021). The uva ursi extract used contains 105 mg arbutin per tablet, and three were given twice daily for 5 days. The uva ursi group ended up taking significantly fewer courses of antibiotics than the fosfomycin group, but was associated with more symptoms. There was a non-significant trend toward a higher rate of pyelonephritis in the uva ursi group than in the fosfomycin group. The mixed results of this trial could in part be interpreted as lack of clear superiority of the uva-ursi, but also that the dosing scheme used was simply insufficient.

A similar trial (dubbed Atafuti) randomized 382 English women with uncomplicated UTIs to a different extract of uva ursi (1200 mg tid, containing 240 mg arbutoside per dose) + advice to take ibuprofen 400 mg tid if needed, placebo + the same ibuprofen advice, uva ursi without ibuprofen advice, and placebo without ibuprofen advice for 3–5 days (Moore, et al. 2019). All participants were given a back-up antibiotic prescription to take if any participant wanted to. The uva ursi extract at this dose was not superior to placebo at reducing urinary symptoms or preventing antibiotic use, though ibuprofen advice was. There were no significant adverse effects with uva ursi and no participants developed pyelonephritis. The reasons for the substantially lower efficacy in this trial compared to the Regatta trial mentioned above are difficult to fathom, other than that possibly the extract used in this trial was in some way inferior.

Given the ongoing rise of antibiotic resistance in uropathogens, such that many formerly first-line antibiotics for this infection are simply no longer effective, uva ursi and other herbal options for uncomplicated UTIs are becoming ever more crucial to assess and adopt (Yarnell 2017; Guay 2008).

Clinically, uva ursi is very helpful in patients with UTIs, with failure most often being associated with under dosing (both low doses and insufficiently frequent doses, both supported by the clinical trials discussed above). Also, It is best when uva ursi is combined with other urinary antiseptics with different chemistries and activities, and with herbs that are diuretic and inflammation modulating with a focus on the urinary tract (see the Classic Formulas section below).

Major Constituents:

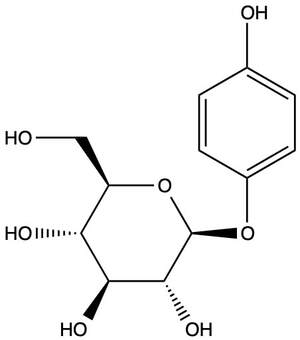

- Phenolic glycosides, most notably arbutoside = arbutin (aglycone hydroquinone), but also methylarbutoside = methylarbutin (aglycone methylhydroquinone) and piceoside (aglycone p-hydroxyacetophenone) (Panusa, et al. 2015; Saleem, et al. 2010; Slaveska-Raicki, et al. 2003). Depending on the season and growing conditions, the arbutoside content of uva-ursi leaves ranges from 6.3–9.2% (Parejo, et al. 2001).

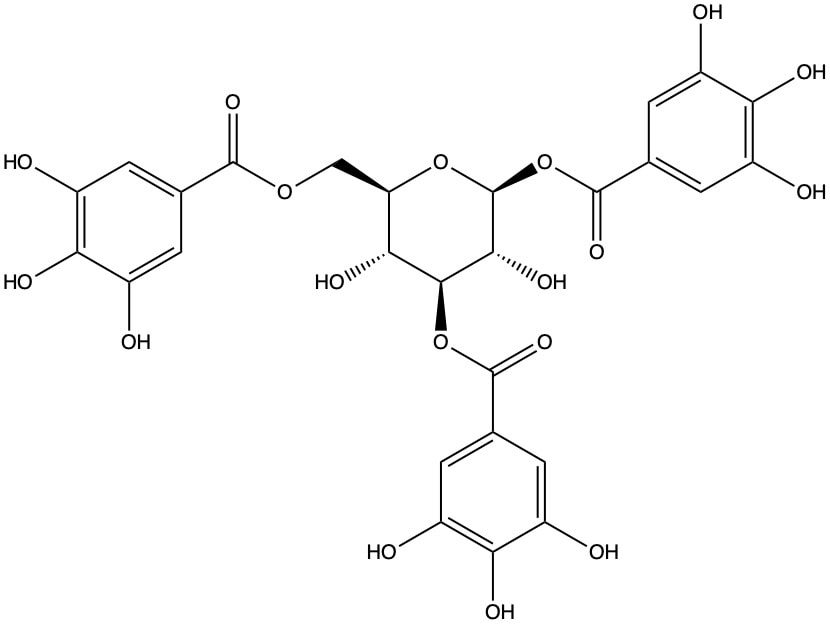

- Tannins, hydrolyzable = gallotannins or ellagitannins (Panusa, et al. 2015; Saleem, et al. 2010; Slaveska-Raicki, et al. 2003; Wähner, et al. 1974), such as corilagin. Tannin content is very high in the leaves, at levels of 20% (Blake, et al. 1994).

- Tannins, condensed

The 2014 European Pharmacopoeia (version 8.1 supplement) requires a minimum of 7% arbutoside in uva ursi leaf sold as medicinal products.

Uva ursi extracts are more effective than isolated arbutoside as urinary antiseptics (Werbach and Murray 2000). This is also believed to be true for greenleaf manzanita, madrone, and related species.

Note that arbutoside is also found in significant levels in several commonly-consumed foods, including pears, wheat, red wine, coffee, tea, and broccoli (Deisinger, et al. 1996). Consumption of all of these foods were shown to increase urine hydroquinone levels in humans and, at least in the case of pears, wheat, coffee, tea, and broccoli (if tolerated by the individual patient) are recommended for consumption during acute UTIs.

Adverse Effects: Other than causing mild-to-moderate nausea, these herbs are very safe. Taking them with food almost always eliminates the nausea problem.

There has been much concern about the fact that uva ursi (and by extension the related plants discussed here) contains some hydroquinone and that more is generated after consumption by hydrolysis of arbutoside. However, the concentration of hydroquinone that has been shown to cause human health hazards (when created by various machines, or when used in industrial processes) is >100 mcg/kg body weight per day; while the maximum amount generated in urine from taking uva ursi is ≤11 mcg/kg body weight per day (de Arriba, et al. 2013). In vitro, hydroquinone generated from arbutoside (i.e. in the presence of bacteria capable of transformating arbutoside) is mutagenic in hamster cells (Blaut, et al. 2006). Epidemological research in humans and animal research do not support that pure hydroquinone is carcinogenic, and some studies show that arbutoside is antineoplastic (Jiang, et al. 2018; Li, et al. 2011; McGregor 2007). Backward extrapolating from the toxicity of isolated hydroquinone (with principal exposure through the skin and lungs in most industrial settings) to complex herbal medicines (with principal exposure after oral intake) is completely illogical.

Rabbits dosed with uva ursi crude extract 25 mg/kg/day for 90 days revealed no toxicity (Saaed, et al. 2014). The oral LD50 for arbutoside in rats was determined to be 8.7 g/kg body weight and for mice 9.8 g/kg body weight, indicating excellent safety of this compound given acutely (SCCS 2015).

Generally these herbs are used short-term (one month is the longest studied period of use in a clinical trial reported; Larsson, et al. 1993). Their primary use, for treating acute UTIs, should generally only require short-term use. However, the author has observed they can be safely taken for months or even years in situations that require ongoing prevention of UTI (in patients with neurogenic bladders, who had to catheterize regularly, or in patients with neobladders after cystectomies to treat bladder cancer).

A 56-year-old woman who took uva ursi for three years (possibly a chronic overdose situation) developed decreased visual acuity and was determined to have bilateral bull's eye maculopathy, which may have developed from chronic inhibition of melanin synthesis in her eyes (Wang and Del Priore 2004). No further cases of this problem were identified, likely indicating that only very long-term overdose would cause such a problem.

Contraindications: It is unclear if uva ursi, greenleaf manzanita, madrone, and related plants are safe in pregnancy or lactation. Some herbalists recommend against them out of an abundance of caution. Michael Moore claims that uva ursi can "decrease placenta-uterine membrane permeability," but gives no support for this assertion (Moore 1993). It is the author's belief that the benefits outweigh the risks for these herbs in treating pregnancy-related UTIs for a period of 3–5 days.

In pregnant rats, the no observable adverse effect level for pure arbutoside is 100 mg/kg of body weight per day delivered subcutaneously, and only mild problems (decreased weight of female fetuses) were seen at subcutaneous arbutoside doses of 400 mg/kg (Itabashi, et al. 1988). Arbutoside is not delivered by this route to humans, and it is therefore very difficult to say how this rat study could possibly be relevant to pregnant women taking whole extracts or intact uva ursi or related herbal products orally and at a far lower dose. A study in guinea pigs found no effect of uva ursi on uterine activity (Shipochliev 1981).

Pregnancy:

Lactation:

Drug Interactions: Experimentally, uva ursi has been shown to actually protect Escherichia coli against ciprofloxacin and ampicillin in vitro, while amplifying the effects of kanamycin (Samoilova, et al. 2014). No human clinical studies are available, and clinically there is no evidence of any such harmful interactions. The Advanced Clinical section below lists studies showing uva ursi can actually decrease antibiotic resistance.

Given the high tannin content of these herbs, they should not generally be given simultaneously with any medication that has reduced effects when taken with food.

In vitro, uva ursi inhibited UDP glucuronyltransferase 1A1, due to its tannin content (Park, et al. 2018). However, because these tannins are minimally absorbed, there was no effect of uva ursi on drugs metabolized by this enzyme. This is an excellent study showing how in vitro results cannot be readily applied to in vivo situations.

Another in vitro study found that uva ursi extracts inhibited CYP3A4/5/7, 2C9, and 2C19 as well as P-glycoprotein (Chauhan, et al. 2007). Such results have also historically been notoriously inaccurate at predicting whether there will be clinical drug-herb interactions, and given that absolutely none have been reported with uva ursi to date, it is unlikely these findings are clinically relevant. Human clinical trials are warranted to be certain, but it is highly unlikely this herb will cause any significant drug interactions by this mechanism (and no interactions consistent with these in vitro findings have been reported clinically).

There has been much concern about the fact that uva ursi (and by extension the related plants discussed here) contains some hydroquinone and that more is generated after consumption by hydrolysis of arbutoside. However, the concentration of hydroquinone that has been shown to cause human health hazards (when created by various machines, or when used in industrial processes) is >100 mcg/kg body weight per day; while the maximum amount generated in urine from taking uva ursi is ≤11 mcg/kg body weight per day (de Arriba, et al. 2013). In vitro, hydroquinone generated from arbutoside (i.e. in the presence of bacteria capable of transformating arbutoside) is mutagenic in hamster cells (Blaut, et al. 2006). Epidemological research in humans and animal research do not support that pure hydroquinone is carcinogenic, and some studies show that arbutoside is antineoplastic (Jiang, et al. 2018; Li, et al. 2011; McGregor 2007). Backward extrapolating from the toxicity of isolated hydroquinone (with principal exposure through the skin and lungs in most industrial settings) to complex herbal medicines (with principal exposure after oral intake) is completely illogical.

Rabbits dosed with uva ursi crude extract 25 mg/kg/day for 90 days revealed no toxicity (Saaed, et al. 2014). The oral LD50 for arbutoside in rats was determined to be 8.7 g/kg body weight and for mice 9.8 g/kg body weight, indicating excellent safety of this compound given acutely (SCCS 2015).

Generally these herbs are used short-term (one month is the longest studied period of use in a clinical trial reported; Larsson, et al. 1993). Their primary use, for treating acute UTIs, should generally only require short-term use. However, the author has observed they can be safely taken for months or even years in situations that require ongoing prevention of UTI (in patients with neurogenic bladders, who had to catheterize regularly, or in patients with neobladders after cystectomies to treat bladder cancer).

A 56-year-old woman who took uva ursi for three years (possibly a chronic overdose situation) developed decreased visual acuity and was determined to have bilateral bull's eye maculopathy, which may have developed from chronic inhibition of melanin synthesis in her eyes (Wang and Del Priore 2004). No further cases of this problem were identified, likely indicating that only very long-term overdose would cause such a problem.

Contraindications: It is unclear if uva ursi, greenleaf manzanita, madrone, and related plants are safe in pregnancy or lactation. Some herbalists recommend against them out of an abundance of caution. Michael Moore claims that uva ursi can "decrease placenta-uterine membrane permeability," but gives no support for this assertion (Moore 1993). It is the author's belief that the benefits outweigh the risks for these herbs in treating pregnancy-related UTIs for a period of 3–5 days.

In pregnant rats, the no observable adverse effect level for pure arbutoside is 100 mg/kg of body weight per day delivered subcutaneously, and only mild problems (decreased weight of female fetuses) were seen at subcutaneous arbutoside doses of 400 mg/kg (Itabashi, et al. 1988). Arbutoside is not delivered by this route to humans, and it is therefore very difficult to say how this rat study could possibly be relevant to pregnant women taking whole extracts or intact uva ursi or related herbal products orally and at a far lower dose. A study in guinea pigs found no effect of uva ursi on uterine activity (Shipochliev 1981).

Pregnancy:

- Mills and Bone 2005: is associated with risk of fetal harms (this is based on research on isolated arbutoside, not uva-ursi, and they state it is theoretical)

- AHPA 2013: theoretical concerns in pregnancy

- Yarnell (expert opinion): safe for short-term use (3–5 days)

Lactation:

- Mills and Bone 2005: strongly discouraged (this is based on research on isolated hydroquinone, not uva-ursi)

- Brinker 2001: uncertain

- AHPA 2013: no information available

- Yarnell (expert opinion): safe for short-term use (3–5 days)

Drug Interactions: Experimentally, uva ursi has been shown to actually protect Escherichia coli against ciprofloxacin and ampicillin in vitro, while amplifying the effects of kanamycin (Samoilova, et al. 2014). No human clinical studies are available, and clinically there is no evidence of any such harmful interactions. The Advanced Clinical section below lists studies showing uva ursi can actually decrease antibiotic resistance.

Given the high tannin content of these herbs, they should not generally be given simultaneously with any medication that has reduced effects when taken with food.

In vitro, uva ursi inhibited UDP glucuronyltransferase 1A1, due to its tannin content (Park, et al. 2018). However, because these tannins are minimally absorbed, there was no effect of uva ursi on drugs metabolized by this enzyme. This is an excellent study showing how in vitro results cannot be readily applied to in vivo situations.

Another in vitro study found that uva ursi extracts inhibited CYP3A4/5/7, 2C9, and 2C19 as well as P-glycoprotein (Chauhan, et al. 2007). Such results have also historically been notoriously inaccurate at predicting whether there will be clinical drug-herb interactions, and given that absolutely none have been reported with uva ursi to date, it is unlikely these findings are clinically relevant. Human clinical trials are warranted to be certain, but it is highly unlikely this herb will cause any significant drug interactions by this mechanism (and no interactions consistent with these in vitro findings have been reported clinically).

Pharmacy Essentials

Tincture: 1:2–1:3 w:v ratio, 30–40% ethanol

Dose:

Acute, adult: 2–3 ml, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, q2h until symptoms have significantly abated then tid-qid until symptoms are completely gone

Chronic, adult: 1–3 ml tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

The upper end of the doses listed are for uva ursi. For madrone and greenleaf manzanita, you can use lower end of the dose range.

Glycerite: 1:3 w:v, 75%+ vegetable glycerin

Dose: same as tincture above

Infusion: Infusion: though this can be made into a hot infusion, it really shines as a cold infusion. Either way, 3–5 g is used per 250–500 ml of water. For a hot infusion, the herb is steeped in the recently boiled water for 15–30 min, strained, and drunk. For a cold infusion it is left to sit for 8–16 hours then strained and drunk.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup six times per day until symptoms significantly abate then 3–4 cups per day until symptoms are completely resolved

Chronic, adult: 1 cup tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Capsules: uva ursi products at least are often standardized to at least 7% arbutoside; greater than 20% is not recommended due to potential loss of synergizing compounds above this level. Madrone and greenleaf manzanita are not readily available in capsules.

Dose:

Acute, adult: 10–12 g per day, providing 400–840 mg arbutoside, in 5 or 6 divided doses for 2–3 days then 1–2 tid-qid until symptoms resolve completely (Blumenthal 2000)

Chronic, adult: 1–2 g tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Dose:

Acute, adult: 2–3 ml, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, q2h until symptoms have significantly abated then tid-qid until symptoms are completely gone

Chronic, adult: 1–3 ml tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

The upper end of the doses listed are for uva ursi. For madrone and greenleaf manzanita, you can use lower end of the dose range.

Glycerite: 1:3 w:v, 75%+ vegetable glycerin

Dose: same as tincture above

Infusion: Infusion: though this can be made into a hot infusion, it really shines as a cold infusion. Either way, 3–5 g is used per 250–500 ml of water. For a hot infusion, the herb is steeped in the recently boiled water for 15–30 min, strained, and drunk. For a cold infusion it is left to sit for 8–16 hours then strained and drunk.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup six times per day until symptoms significantly abate then 3–4 cups per day until symptoms are completely resolved

Chronic, adult: 1 cup tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Capsules: uva ursi products at least are often standardized to at least 7% arbutoside; greater than 20% is not recommended due to potential loss of synergizing compounds above this level. Madrone and greenleaf manzanita are not readily available in capsules.

Dose:

Acute, adult: 10–12 g per day, providing 400–840 mg arbutoside, in 5 or 6 divided doses for 2–3 days then 1–2 tid-qid until symptoms resolve completely (Blumenthal 2000)

Chronic, adult: 1–2 g tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Other Names: Arctostaphylos uva-ursi

Latin synonyms:

Current correct Latin binomial: Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L) Spreng

Arbutus acerba Gilib

Arbutus buxifolia Stokes

Arbutus officinalis Boiss

Arbutus procumbens Salisb

Arbutus uva-ursi L

Arctostaphylos adenotricha (Fernald & JF Macbr) Á Löve, D Löve & BM Kapoor

Arctostaphylos angustifolia Payot

Arctostaphylos officinalis Wimm & Grab.

Arctostaphylos procumbens (Moench) E Mey

Daphnidostaphylis fendleri Klotzsch

Daphnidostaphylis fendleriana Klotzsch

Mairrania uva-ursi (L) Desv

Uva-ursi buxifolia Gray

Uva-ursi procumbens Moench

English Common Names: uva ursi, bearberry, kinnikinnick, pinemat manzanita, bear-grape, bearberry, common bearberry, hog cranberry , mealberry, mountain box, mountain cranberry, red bearberry, rockberry

Note: kinnikinnick < Unami (Delaware) kələkːəˈnikːan, "mixture" , similar to Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) giniginige "to mix animate/inanimate items" < Proto-Algonquian *kereken-, "mix (it) with something different by hand." These names clearly refer to its importance as an admixture with tobacco, Cornus sericea (red osier dogwood), and other plants in smoking mixtures.

Anishinaabemowin (Chippewa, Ojibwe) Common Name: saccacomis, sac comis, sagakomi, segockimac, segockiniac (all mean "mixture")

Arabic Common Names: عنب الدب, عيسران

Armenian Common Name: Մարուղենի

Atna' kenaege (Copper River) Common Name: dziidzi naegge' ("duck's eye")

Bulgarian Common Name: Мечо грозде

Catalan Common Names: boixerola, barruixes, boixereta, boixerina, boixeringa, boixerol, farigoler, farinell, faringoles, farinjoler, farinola, farnola, gallufa, gallufera, muixes, raïm d'óssa

Croatian Common Name: medvjetkin

Czech Common Names: medvědicový list, medvědice lékařská, medvědice otajská

Danish Common Names: hede-melbærris, melbærris, bjørnebær, hede-melbær, melbær, stedsegrøn melbær, stedsegrøn melbærris

Dutch Common Names: berendruif, beredruif, beredruifsoort

Esperanto Common Names: ursbera arktostafilo, arktostafilo, ordinara arktostafilo, ursa bero, uva de l' urso

Estonian Common Names: harilik leesikas, leesikaleht

Farsi Common Name: تنباکوی کینیکینیک

Finnish Common Name: sianpuolukka

French Common Names: busserole, raisin d'ours, arbousier trainant, bousserole, busserole officinal, buxerole, petit buis, raisin-d'ours commun, rasin d'ours

German Common Names: echte Bärentraube, immergrüne Bärentraube, Bärentraube, Bärentraubenblatt, gemeine Bärentraube, gewöhnliche Bärentraube, Mehlbeere, Moosbeere, rotfrüchtige Bärentraube, Sandbeere, Steinbeere

Greek (Modern) Common Name: Φύλλο αρκτοκομάρου

Halq̓eméylem (Upriver Halkomelem) Common Name: tl'íkw'el

Hebrew (Modern) Common Names: ענבי הדב, ענבי דב

Hungarian Common Names: medveszőlő, medveáfonya, orvosi medveszőlő

Icelandic Common Name: sortulyng

Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit (Yakama) Common Name: ilík

Irish Common Names: lus na stalóg, blanchnog

Italian Common Name: uva ursina

Japanese Common Name: クマコケモモ

Kumeyaay: hasil, jusilh, josilh, hw'willy, hesill (for A. pungens and other shrubby desert species)

Kwak'wala (Kwakiutl) Common Name: kwa’-atum (fruit)

Latvian Common Name: miltenes

Lithuanian Common Name: neškauogių

Maltese Common Name: ulva ursi

Mandarin Chinese Common Names: 熊莓 xióng méi ("bear bush"), 熊果 xióng guǒ ("bear fruit")

Norwegian Common Names: melbær, mjølbær, mildebær, mjøltryt

Pâri Pakûru' (Pawnee) Common Name: nakasis ("little tree", may refer to shrubby species and not uva ursi)

Polish Common Names: liść mącznicy, mącznica lekarska, chrościna, mącznica garbarska, niedźwiedzie grono

Portuguese Common Names: uva-de-urso, uva-ursi, uva ursina

Romanian Common Name: strugurii ursului

Russian Common Names: Толокнянка обыкновенная, Медвежьи ушки, Медвежьи ушкитолокнянка, Толокнянка аптечная, Толокнянка лежачая

Scottish Gaelic Common Names: gràinnseag, cnàimhseag, goirt-dhearc ("sour grape"), lus na géire-boireannach ("herb of the sour/bitter woman")

Serbian Common Names: Медвеђе грожђе (Medveđe grožđe), Медведје гроздје (Medvedje grozdje), Медвеђе уво (Medveđe uvo), Ува (Uva)

Siksiká (Blackfoot) Common Name: kakahsiin

Slovak Common Names: medvedica lekárska, medvedice

Slovenian Common Names: gornik vednozeleni, vednozeleni gornik, zimzeleni

Spanish Common Names: gayuba, aguarilla, aguavilla, azunges, branca ursina, bujarola, manzanera, manzaneta, manzanilla de pastor, uruga, uva de oso, uvaduz

Swedish Common Names: mjölon, mjölbär

Ukranian Common Name: Мучниця звичайна

Welsh Common Name: llusen-yr-arth goch

xwləšucid (Lushootseed) Common Name: ḱayuḱayu (plant), skw lsé (fruit)

Yawelmani (Valley Yokuts) Common Name: ʔapṭ'uw

Arctostaphylos < Greek ἄρκος, ἄρκτος "bear," and σταφυλή "a bunch of grapes." uva-ursi <Latin uva "grape" and ursus "bear." So arguably A. uva-ursi translates as bearberry bearberry, with a common name of bearberry, in case there was any question of whether bears like the fruit of this plant.

Current correct Latin binomial: Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L) Spreng

Arbutus acerba Gilib

Arbutus buxifolia Stokes

Arbutus officinalis Boiss

Arbutus procumbens Salisb

Arbutus uva-ursi L

Arctostaphylos adenotricha (Fernald & JF Macbr) Á Löve, D Löve & BM Kapoor

Arctostaphylos angustifolia Payot

Arctostaphylos officinalis Wimm & Grab.

Arctostaphylos procumbens (Moench) E Mey

Daphnidostaphylis fendleri Klotzsch

Daphnidostaphylis fendleriana Klotzsch

Mairrania uva-ursi (L) Desv

Uva-ursi buxifolia Gray

Uva-ursi procumbens Moench

English Common Names: uva ursi, bearberry, kinnikinnick, pinemat manzanita, bear-grape, bearberry, common bearberry, hog cranberry , mealberry, mountain box, mountain cranberry, red bearberry, rockberry

Note: kinnikinnick < Unami (Delaware) kələkːəˈnikːan, "mixture" , similar to Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) giniginige "to mix animate/inanimate items" < Proto-Algonquian *kereken-, "mix (it) with something different by hand." These names clearly refer to its importance as an admixture with tobacco, Cornus sericea (red osier dogwood), and other plants in smoking mixtures.

Anishinaabemowin (Chippewa, Ojibwe) Common Name: saccacomis, sac comis, sagakomi, segockimac, segockiniac (all mean "mixture")

Arabic Common Names: عنب الدب, عيسران

Armenian Common Name: Մարուղենի

Atna' kenaege (Copper River) Common Name: dziidzi naegge' ("duck's eye")

Bulgarian Common Name: Мечо грозде

Catalan Common Names: boixerola, barruixes, boixereta, boixerina, boixeringa, boixerol, farigoler, farinell, faringoles, farinjoler, farinola, farnola, gallufa, gallufera, muixes, raïm d'óssa

Croatian Common Name: medvjetkin

Czech Common Names: medvědicový list, medvědice lékařská, medvědice otajská

Danish Common Names: hede-melbærris, melbærris, bjørnebær, hede-melbær, melbær, stedsegrøn melbær, stedsegrøn melbærris

Dutch Common Names: berendruif, beredruif, beredruifsoort

Esperanto Common Names: ursbera arktostafilo, arktostafilo, ordinara arktostafilo, ursa bero, uva de l' urso

Estonian Common Names: harilik leesikas, leesikaleht

Farsi Common Name: تنباکوی کینیکینیک

Finnish Common Name: sianpuolukka

French Common Names: busserole, raisin d'ours, arbousier trainant, bousserole, busserole officinal, buxerole, petit buis, raisin-d'ours commun, rasin d'ours

German Common Names: echte Bärentraube, immergrüne Bärentraube, Bärentraube, Bärentraubenblatt, gemeine Bärentraube, gewöhnliche Bärentraube, Mehlbeere, Moosbeere, rotfrüchtige Bärentraube, Sandbeere, Steinbeere

Greek (Modern) Common Name: Φύλλο αρκτοκομάρου

Halq̓eméylem (Upriver Halkomelem) Common Name: tl'íkw'el

Hebrew (Modern) Common Names: ענבי הדב, ענבי דב

Hungarian Common Names: medveszőlő, medveáfonya, orvosi medveszőlő

Icelandic Common Name: sortulyng

Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit (Yakama) Common Name: ilík

Irish Common Names: lus na stalóg, blanchnog

Italian Common Name: uva ursina

Japanese Common Name: クマコケモモ

Kumeyaay: hasil, jusilh, josilh, hw'willy, hesill (for A. pungens and other shrubby desert species)

Kwak'wala (Kwakiutl) Common Name: kwa’-atum (fruit)

Latvian Common Name: miltenes

Lithuanian Common Name: neškauogių

Maltese Common Name: ulva ursi

Mandarin Chinese Common Names: 熊莓 xióng méi ("bear bush"), 熊果 xióng guǒ ("bear fruit")

Norwegian Common Names: melbær, mjølbær, mildebær, mjøltryt

Pâri Pakûru' (Pawnee) Common Name: nakasis ("little tree", may refer to shrubby species and not uva ursi)

Polish Common Names: liść mącznicy, mącznica lekarska, chrościna, mącznica garbarska, niedźwiedzie grono

Portuguese Common Names: uva-de-urso, uva-ursi, uva ursina

Romanian Common Name: strugurii ursului

Russian Common Names: Толокнянка обыкновенная, Медвежьи ушки, Медвежьи ушкитолокнянка, Толокнянка аптечная, Толокнянка лежачая

Scottish Gaelic Common Names: gràinnseag, cnàimhseag, goirt-dhearc ("sour grape"), lus na géire-boireannach ("herb of the sour/bitter woman")

Serbian Common Names: Медвеђе грожђе (Medveđe grožđe), Медведје гроздје (Medvedje grozdje), Медвеђе уво (Medveđe uvo), Ува (Uva)

Siksiká (Blackfoot) Common Name: kakahsiin

Slovak Common Names: medvedica lekárska, medvedice

Slovenian Common Names: gornik vednozeleni, vednozeleni gornik, zimzeleni

Spanish Common Names: gayuba, aguarilla, aguavilla, azunges, branca ursina, bujarola, manzanera, manzaneta, manzanilla de pastor, uruga, uva de oso, uvaduz

Swedish Common Names: mjölon, mjölbär

Ukranian Common Name: Мучниця звичайна

Welsh Common Name: llusen-yr-arth goch

xwləšucid (Lushootseed) Common Name: ḱayuḱayu (plant), skw lsé (fruit)

Yawelmani (Valley Yokuts) Common Name: ʔapṭ'uw

Arctostaphylos < Greek ἄρκος, ἄρκτος "bear," and σταφυλή "a bunch of grapes." uva-ursi <Latin uva "grape" and ursus "bear." So arguably A. uva-ursi translates as bearberry bearberry, with a common name of bearberry, in case there was any question of whether bears like the fruit of this plant.

Interchangeability of Species

There are numerous medicinal species in the Arctostaphylos genus (see table below) and the Arbutus genus, as highlighted by the three key species mentioned in this monograph. Some of these clearly have lower arbutoside levels than uva ursi, such as A. pungens (pointleaf manzanita) (Panusa, et al. 2015; Gallo, et al. 2013). The leaves of Arbutus menziesii (madrone), a different species also in the Ericaceae family, were demonstrated to have five times as much arbutoside as uva ursi (Brigitte Zettl, unpublished research, Bastyr University). Clinically, madrone has proven to be a superior medicine to uva ursi.

Shrubby Arctostaphylos Species (Manzanitas) of North America

| Species | Common name(s) | Distinguishing features |

| A. bakeri | Baker's manzanita | elliptical-to-ovate, erect leaves; ovary glabrous; fruit glabrous, 8–10 mm wide |

| A. canescens | hoary manzanita | elliptical, ovate or round, erect leaves; tomentose stems; fruit sparsely hairy, 5–10 mm wide |

| A. columbiana | hairy manzanita | very common; distal stems, fruit, ovary, and oval leaves (both surfaces) hairy, inconsistently glandular; spreading leaves; fruit 8–11 mm wide |

| A. glandulosa | Eastwood's manzanita | elliptical-to-ovate, erect/ascending, variably hairy leaves; fruit glabrous, 6–10 mm wide |

| A. manzanita | common manzanita | ovate-to-obovate, erect, glabrous leaves; fruit 8–12 mm wide |

| A. nevadensis | pinemat manzanita | ovate-to-obovate, erect, finely hairy (glabrous when old) leaves; glabrous ovary; fruit glabrous, 6–8 mm wide |

| A. patula | greenleaf manzanita | ovate-to-round, glabrous, erect leaves; ovary glabrous or hairy; fruit glabrous, 7–10 mm wide |

| A. pringlei | Pringle's manzanita | oval, erect, finely hairy leaves; ovary glandular hairy; fruit hairy and sticky, 5–8 mm wide |

| A. pungens | pointleaf manzanita | elliptical leaves sparsely hairy; ovary glabrous; erect leaves; fruit glabrous, 5–8 mm wide |

| A. tomentosa | woolyleaf manzanita | gray bark on old stems; oblong-ovate to lance-oblong, spreading, finely hairy leaves; ovary hairy; fruit hairy, 6–10 mm wide |

| A. viscida | sticky manzanita | ovate-to-round, glabrous or hairy, erect leaves; sticky flowers and pedicels; fruit 6–8 mm wide |

Advanced Clinical Information

Additional Actions:

The ellagitannin compound corilagin, found in uva ursi among a range of other plants, has repeatedly been shown to restore sensitivity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) to β-lactams in vitro (Shimizu et al. 2001). Subsequent research determined this was significantly due to inhibition of MRSA's penicillin-binding proteins by corilagin and likely other tannins (Shiota, et al. 2004). Because these compounds are not absorbed to any significant extent, this would not likely work for increasing antibiotic activity against MRSA systemically, but could be very relevant for skin and gut infections with this microbe. A separate study showed that uva ursi strongly potentiated the antimicrobial activity of nisin against a range of food-born pathogens (Dykes, et al. 2003).

Additional Indications:

Though many sources caution against the use of uva ursi and related plants for upper urinary tract infections or pyelonephritis, this is based solely around the idea that such infections are too serious for any plant medicine to possibly help. The author suspects that in fact many patients who present with supposedly lower UTIs actually have upper UTIs at the same time, as the symptoms of the two overlap significantly, and that many such patients have been treated with herbs successfully. Obviously this should only be attempted in patients that are willing to undertake the frequent dosing required, who are willing to follow-up regularly, and who have demonstrated their commitment and diligence. In such cases, it is recommended that a checkin is needed every 12- to 24-hours to insure that symptoms are either improving, or at least staying stable in the first 24 hours (and improving after that). If of course symptoms worsen, an antibiotic drug can always be prescribed. It is strongly recommended to formula uva ursi and related plants together with other herbs for patients with pyelonephritis.

Uva ursi-, arbutoside-, and hydroquinone-containing products are frequently used topically as skin lighteners. Hydroquinone released from or contained in these these products inhibit melanin synthesis by blocking tyrosinase, thereby lightening skin (Solano, et al. 2006). The use of skin-lightening products containing arbutoside or hydroquinone is extremely widespread among people of color, and is obviously very politically and culturally fraught (Bhatia 2017; Cooper 2016; Danielle 2015; Hall 1995 and 1994). Obviously, in most places, white people hold the greatest power and social esteem, propagated through the history of European colonialism. Social pressures and marketing promoting skin lightening in populations affected by these messages are enormous, and the reasons for skin lightening are intense. A similar process occurred in the US and elsewhere that accelerated in the 1960s when "kinky" (read: African/non-white) hair became increasingly viewed as disdainful, leading to a huge rise in the use of hair-straightening products by African-American and other people. The trend predated this, as evidenced by the story of the first female African-American millionaire Madam C. J. Walker, born Sarah Breedlove (1867–1919). She developed a successful business selling hair-straightening and other beauty products primarily to African-American women. Her story further emphasizes the complex nature of these issues.

There is no reason or intention to make anyone feel guilty for using skin-lightening products, whether they contain hydroquinone or other products. However, it is important to find out if a patient is engaging in this practice, as hydroquinone-containing products can have long-term hazardous effects, including but not limited to ochronosis, cataracts, nail pigmentation, reduced wound healing, increased risk of sun damage and skin cancers, pigmented colloid milia, loss of skin elasticity, and maculopathy (Nordlund, et al. 2006). These products are effective for treating melasma (Jutley, et al. 2014), though again generally this is not medically necessary, but is informed by multiple complex cultural and sociopolitical pressures about notions of beauty and social status. If used, they should be stopped as soon as is practical once pregnancy is over to avoid adverse effects. Bringing up this topic with patients can be extremely difficult as it is a relative social taboo to discuss, and the reasons and emotions behind it are very complex. Don't assume anything, and work to keep the conversation medical and non-judgemental.

Pharmacokinetics: After oral intake of uva ursi (either in film-coated tablets or an infusion), approximately 65% of the ingested arbutoside ended up in the urine as hydroquinone equivalents (based on averages), with substantial intersubject variability (Schindler, et al. 2002). Major urinary metabolites of hydroquinone are hydroquinone glucuronide and hydroquinone sulfate.

Another human trial investigated the pharmacokinetics of an uva ursi extract 945 mg, of which 210 mg was arbutoside (Glöckl, et al. 2001). Within 4 h, about half the arbutoside was accounted for as hydroquinone metabolites in urine. Urine concentrations of these metabolites were, on average, 224.5 μmol/L of hydroquinone glucuronide and 182 μmol/L of hydroquinone sulfate.

Human colonic bacteria, notably Eubacterium ramulus, Enterococcus casseliflavus, Bacteroides distasonis, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, and B. longum convert arbutoside into hydroquinone with high efficiency, while human intestinal and colonic epithelial cells make this conversion with very low activity in vitro (Blaut, et al. 2006; Kang, et al. 2011).

It is frequently said that the urine must be alkaline for release of hydroquinone from various conjugates such as hydroquinone glucuronide. This is true, if there is to be spontaneous degradation and release of the active compounds. However, urine collected from healthy human volunteers who consumed an uva ursi extract or arbutoside was shown to develop large amounts of both intracellular and extracellular hydroquinone when incubated with E. coli in two studies (Siegers, et al. 2003 and 1997). This strongly suggests the target pathogens in the urine deconjugate hydroquinone metabolites, presumably gaining the benefit of the sugar or uronic acid they release in this process (frequently; sulfate deconjugation by these bacteria has also been demonstrated), but in the process exposing themselves to the hazards of hydroquinone. Urine alkalinization has never been proven necessary for uva uris to work clinically, and various urine acidifiers have not been shown to interfere with uva ursi. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus epidermidis isolated from human skin have also been shown to deconjugate arbutoside to hydroquinone directly (Bang, et al. 2008).

- Antigonorrheal (Cybulska, et al. 2011)

- Anti-Helicobacter pylori (Anuuk, et al. 1999)

- Antineoplastic (Jiang, et al. 2018; Li, et al. 2011)

- Anti-Staphylococcus (Snowden, et al. 2014)

- Aquaretic, not diuretic, in rats (Beaux, et al. 1999)

- Increase microbial cell hydrophobicity thus reducing adhesion (Türi, et al. 1997)

- Inflammation modulating (Matsuda, et al. 1992, 1991 and 1990; Kubo, et al. 1990)

- Resistance inhibitor (Shiota, et al. 2004; Dykes, et al. 2003; Shimizu, et al. 2001)

The ellagitannin compound corilagin, found in uva ursi among a range of other plants, has repeatedly been shown to restore sensitivity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) to β-lactams in vitro (Shimizu et al. 2001). Subsequent research determined this was significantly due to inhibition of MRSA's penicillin-binding proteins by corilagin and likely other tannins (Shiota, et al. 2004). Because these compounds are not absorbed to any significant extent, this would not likely work for increasing antibiotic activity against MRSA systemically, but could be very relevant for skin and gut infections with this microbe. A separate study showed that uva ursi strongly potentiated the antimicrobial activity of nisin against a range of food-born pathogens (Dykes, et al. 2003).

Additional Indications:

- Dysentery

- Irritable bladder, in formula (Lenau, et al. 1984)

- Lymphedema after breast cancer surgery, in formula (Cacchio, et al. 2019a)

- Lymphedema after hand surgery, in formula (Cacchio, et al. 2019b)

- Melasma (Jutley, et al. 2014)

- Menorrhagia

- Prostatitis, chronic (Busetto, et al. 2014)

- Pyelonephritis

Though many sources caution against the use of uva ursi and related plants for upper urinary tract infections or pyelonephritis, this is based solely around the idea that such infections are too serious for any plant medicine to possibly help. The author suspects that in fact many patients who present with supposedly lower UTIs actually have upper UTIs at the same time, as the symptoms of the two overlap significantly, and that many such patients have been treated with herbs successfully. Obviously this should only be attempted in patients that are willing to undertake the frequent dosing required, who are willing to follow-up regularly, and who have demonstrated their commitment and diligence. In such cases, it is recommended that a checkin is needed every 12- to 24-hours to insure that symptoms are either improving, or at least staying stable in the first 24 hours (and improving after that). If of course symptoms worsen, an antibiotic drug can always be prescribed. It is strongly recommended to formula uva ursi and related plants together with other herbs for patients with pyelonephritis.

Uva ursi-, arbutoside-, and hydroquinone-containing products are frequently used topically as skin lighteners. Hydroquinone released from or contained in these these products inhibit melanin synthesis by blocking tyrosinase, thereby lightening skin (Solano, et al. 2006). The use of skin-lightening products containing arbutoside or hydroquinone is extremely widespread among people of color, and is obviously very politically and culturally fraught (Bhatia 2017; Cooper 2016; Danielle 2015; Hall 1995 and 1994). Obviously, in most places, white people hold the greatest power and social esteem, propagated through the history of European colonialism. Social pressures and marketing promoting skin lightening in populations affected by these messages are enormous, and the reasons for skin lightening are intense. A similar process occurred in the US and elsewhere that accelerated in the 1960s when "kinky" (read: African/non-white) hair became increasingly viewed as disdainful, leading to a huge rise in the use of hair-straightening products by African-American and other people. The trend predated this, as evidenced by the story of the first female African-American millionaire Madam C. J. Walker, born Sarah Breedlove (1867–1919). She developed a successful business selling hair-straightening and other beauty products primarily to African-American women. Her story further emphasizes the complex nature of these issues.

There is no reason or intention to make anyone feel guilty for using skin-lightening products, whether they contain hydroquinone or other products. However, it is important to find out if a patient is engaging in this practice, as hydroquinone-containing products can have long-term hazardous effects, including but not limited to ochronosis, cataracts, nail pigmentation, reduced wound healing, increased risk of sun damage and skin cancers, pigmented colloid milia, loss of skin elasticity, and maculopathy (Nordlund, et al. 2006). These products are effective for treating melasma (Jutley, et al. 2014), though again generally this is not medically necessary, but is informed by multiple complex cultural and sociopolitical pressures about notions of beauty and social status. If used, they should be stopped as soon as is practical once pregnancy is over to avoid adverse effects. Bringing up this topic with patients can be extremely difficult as it is a relative social taboo to discuss, and the reasons and emotions behind it are very complex. Don't assume anything, and work to keep the conversation medical and non-judgemental.

Pharmacokinetics: After oral intake of uva ursi (either in film-coated tablets or an infusion), approximately 65% of the ingested arbutoside ended up in the urine as hydroquinone equivalents (based on averages), with substantial intersubject variability (Schindler, et al. 2002). Major urinary metabolites of hydroquinone are hydroquinone glucuronide and hydroquinone sulfate.

Another human trial investigated the pharmacokinetics of an uva ursi extract 945 mg, of which 210 mg was arbutoside (Glöckl, et al. 2001). Within 4 h, about half the arbutoside was accounted for as hydroquinone metabolites in urine. Urine concentrations of these metabolites were, on average, 224.5 μmol/L of hydroquinone glucuronide and 182 μmol/L of hydroquinone sulfate.

Human colonic bacteria, notably Eubacterium ramulus, Enterococcus casseliflavus, Bacteroides distasonis, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, and B. longum convert arbutoside into hydroquinone with high efficiency, while human intestinal and colonic epithelial cells make this conversion with very low activity in vitro (Blaut, et al. 2006; Kang, et al. 2011).

It is frequently said that the urine must be alkaline for release of hydroquinone from various conjugates such as hydroquinone glucuronide. This is true, if there is to be spontaneous degradation and release of the active compounds. However, urine collected from healthy human volunteers who consumed an uva ursi extract or arbutoside was shown to develop large amounts of both intracellular and extracellular hydroquinone when incubated with E. coli in two studies (Siegers, et al. 2003 and 1997). This strongly suggests the target pathogens in the urine deconjugate hydroquinone metabolites, presumably gaining the benefit of the sugar or uronic acid they release in this process (frequently; sulfate deconjugation by these bacteria has also been demonstrated), but in the process exposing themselves to the hazards of hydroquinone. Urine alkalinization has never been proven necessary for uva uris to work clinically, and various urine acidifiers have not been shown to interfere with uva ursi. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus epidermidis isolated from human skin have also been shown to deconjugate arbutoside to hydroquinone directly (Bang, et al. 2008).

Classic Formulas

Dr. Silena Heron's Urinary Antiseptic Formula

Silena Heron, RN, ND (1947–2005) was the first chair of botanical medicine at Bastyr University. She used this formula to great effect in many patients with urinary tract infections over her decades in clinical practice. Note the use of multiple overlapping urinary tract tonics and not a reliance solely on antimicrobial herbs.

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi} (uva ursi) tincture 20%

Agathosma betulina (buchu) tincture 20%

Equisetum arvense (horsetail) syrup 15%

Aphanes arvensis (parsley-piert) tincture 15%

Elymus repens (couch grass) glycerite 10%

Parietaria judaica (pellitory-of-the-wall) tincture 10%

Solidago virgaurea (goldenrod) tincture 10%

Sig: 1 tsp q2h for 2–3 days then tid-qid until symptoms completely resolved (and sometimes, until urinalysis testing was completely clear, for patients with more serious infections).

Dr. Yarnell's Urinary Tract Infection Fighter Formula

Arbutus menziesii (madrone) leaf tincture 30%

Solidago canadensis (goldenrod) aerial parts tincture 20%

Thymus vulgaris (thyme) aerial parts tincture 15%

Juniperus communis (juniper) seed cone tincture 15%

Fouquieria splendens (ocotillo) bark tincture 10%

Zingiber officinale (ginger) dry rhizome glycerite or tincture 5%

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) dry root glycerite or tincture 5%

Juniperus communis (juniper) seed cone steam-distilled volatile oil, 5 drops/4 oz

Thymus vulgaris ct thymol (red thyme) aerial parts steam-distilled volatile oil, 5 drops/4 oz

Sig: take 1 tsp q2h during for acute UTI. If symptoms are not dramatically better in 12–24 hours (if pyelonephritis is suspected, or for complicated UTI) or in 36–48 hours (for uncomplicated lower UTI), consider antibiotic therapy. If symptoms are waning after 48 hours then reduce dose to 1 tsp 4–5 times per day until symptoms are completely gone.

For pregnancy-related UTI, especially in the first trimester, substitute Salvia officinalis (garden sage) for the juniper and leave out the volatile oils. Do not dose for more than five days.

Smoking Mixtures

For a nice review of the use of kinnikinnick in smoking mixtures, and on this topic in general, see this website from the Lewis and Clark expedition wiki. Note that smoking any herbs is harmful to lung if done on a chronic basis and is only recommended for short-term or brief use.

Silena Heron, RN, ND (1947–2005) was the first chair of botanical medicine at Bastyr University. She used this formula to great effect in many patients with urinary tract infections over her decades in clinical practice. Note the use of multiple overlapping urinary tract tonics and not a reliance solely on antimicrobial herbs.

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi} (uva ursi) tincture 20%

Agathosma betulina (buchu) tincture 20%

Equisetum arvense (horsetail) syrup 15%

Aphanes arvensis (parsley-piert) tincture 15%

Elymus repens (couch grass) glycerite 10%

Parietaria judaica (pellitory-of-the-wall) tincture 10%

Solidago virgaurea (goldenrod) tincture 10%

Sig: 1 tsp q2h for 2–3 days then tid-qid until symptoms completely resolved (and sometimes, until urinalysis testing was completely clear, for patients with more serious infections).

Dr. Yarnell's Urinary Tract Infection Fighter Formula

Arbutus menziesii (madrone) leaf tincture 30%

Solidago canadensis (goldenrod) aerial parts tincture 20%

Thymus vulgaris (thyme) aerial parts tincture 15%

Juniperus communis (juniper) seed cone tincture 15%

Fouquieria splendens (ocotillo) bark tincture 10%

Zingiber officinale (ginger) dry rhizome glycerite or tincture 5%

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) dry root glycerite or tincture 5%

Juniperus communis (juniper) seed cone steam-distilled volatile oil, 5 drops/4 oz

Thymus vulgaris ct thymol (red thyme) aerial parts steam-distilled volatile oil, 5 drops/4 oz

Sig: take 1 tsp q2h during for acute UTI. If symptoms are not dramatically better in 12–24 hours (if pyelonephritis is suspected, or for complicated UTI) or in 36–48 hours (for uncomplicated lower UTI), consider antibiotic therapy. If symptoms are waning after 48 hours then reduce dose to 1 tsp 4–5 times per day until symptoms are completely gone.

For pregnancy-related UTI, especially in the first trimester, substitute Salvia officinalis (garden sage) for the juniper and leave out the volatile oils. Do not dose for more than five days.

Smoking Mixtures

For a nice review of the use of kinnikinnick in smoking mixtures, and on this topic in general, see this website from the Lewis and Clark expedition wiki. Note that smoking any herbs is harmful to lung if done on a chronic basis and is only recommended for short-term or brief use.

Monograph from Eclectic Materia Medica (Felter 1922)

UVA URSI

The dried leaves of Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (Linné), Sprengel (Nat. Ord. Ericaceae). A perennial evergreen common in the northern part of Europe and North America. Dose, 30 to 60 grains.

Common Names: Uva Ursi, Bearberry, Upland Cranberry.

Principal Constituents.—A bitter glucoside arbutin (C12H16O7), yielding hydroquinone, methyl-hydroquinone, and glucose; ericolin (C10H16O), ursone, tannic and gallic acids.

Preparation.—Specific Medicine Uva Ursi. Dose, 5 to 60 drops.

Specific Indications.—Relaxed urinary tract, with pain and bloody or mucous secretions; weight and dragging in the loins and perineum not due to prostatic enlargement; chronic irritation of the bladder, with pain, tenesmus, and catarrhal discharge.

Action and Therapy.—Uva Ursi is a true diuretic acting directly upon the renal epithelium. Owing to the presence of arbutin it is decidedly antiseptic and retards putrescent changes in the urine, and acts as a mild disinfectant of the urinary passages. It is to be used where the tissues are relaxed and toneless, with dragging and weighty feeling, and much mucoid or muco-bloody discharge. There is always a feeble circulation and lack of innervation when uva ursi is indicated. It is especially valuable in chronic irritation of the bladder, in vesical catarrh, strangury, and gonorrhea with bloody urination. It is claimed that when cystic calculi are present uva ursi, by blunting sensibility, enables their presence to be more comfortably borne. Pyelitis and mild renal haematuria sometimes improve under the use of uva ursi. Arbutin, in its passage through the system, yields hydroquinone, and this body, further changed by oxidation, renders the urine dark or brownish-green. This should be explained to patients taking the drug in order to allay any unnecessary fears the phenomenon may excite.

The dried leaves of Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (Linné), Sprengel (Nat. Ord. Ericaceae). A perennial evergreen common in the northern part of Europe and North America. Dose, 30 to 60 grains.

Common Names: Uva Ursi, Bearberry, Upland Cranberry.

Principal Constituents.—A bitter glucoside arbutin (C12H16O7), yielding hydroquinone, methyl-hydroquinone, and glucose; ericolin (C10H16O), ursone, tannic and gallic acids.

Preparation.—Specific Medicine Uva Ursi. Dose, 5 to 60 drops.

Specific Indications.—Relaxed urinary tract, with pain and bloody or mucous secretions; weight and dragging in the loins and perineum not due to prostatic enlargement; chronic irritation of the bladder, with pain, tenesmus, and catarrhal discharge.

Action and Therapy.—Uva Ursi is a true diuretic acting directly upon the renal epithelium. Owing to the presence of arbutin it is decidedly antiseptic and retards putrescent changes in the urine, and acts as a mild disinfectant of the urinary passages. It is to be used where the tissues are relaxed and toneless, with dragging and weighty feeling, and much mucoid or muco-bloody discharge. There is always a feeble circulation and lack of innervation when uva ursi is indicated. It is especially valuable in chronic irritation of the bladder, in vesical catarrh, strangury, and gonorrhea with bloody urination. It is claimed that when cystic calculi are present uva ursi, by blunting sensibility, enables their presence to be more comfortably borne. Pyelitis and mild renal haematuria sometimes improve under the use of uva ursi. Arbutin, in its passage through the system, yields hydroquinone, and this body, further changed by oxidation, renders the urine dark or brownish-green. This should be explained to patients taking the drug in order to allay any unnecessary fears the phenomenon may excite.

Monograph from Physiomedical Dispensatory (Cook 1869)

ARCTOSTAPHALOS UVA URSI, UVA URSI, BEARBERRY, UPLAND CRANBERRY

Synonym: Arbutus uva-ursi

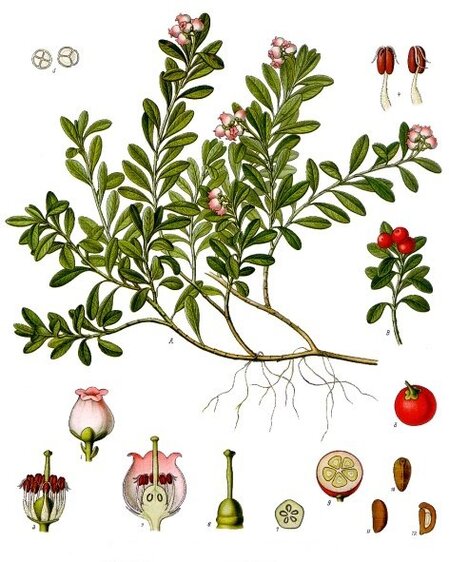

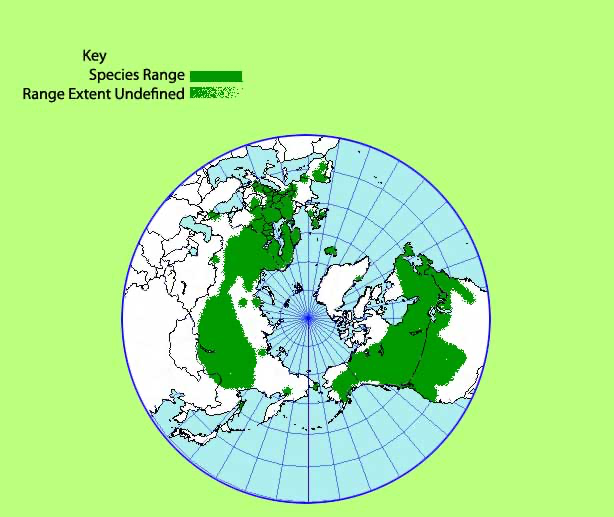

Description: Natural Order, Ericaceae. An evergreen shrub, of the heath family; common to the Northern parts of America, Europe, and Asia; preferring sandy and elevated positions. Stem prostrate, trailing, round, woody, several feet in length, covered with a deciduous bark; young branches erect, three to eight inches. Leaves, alternate, on short petioles, thick and leathery, entire, dark-green and smooth above, paler and veined beneath, obovate, half inch to an inch long. Flowers nearly white, tinted rose-pink; in short, terminal, drooping clusters. Calyx small, red, persistent; five-parted. Corolla ovoid, swollen at the base; with five small, reduced segments on the limb. Stamens ten, on the base of the corolla, with downy filament and red anthers. Fruit deep red, resembling a cranberry, nearly as large as a currant, tasteless, with five long and closely united seeds in the nucleus. Flowers June to September. Berries ripen during the winter.

The leaves of this plant are used in medicine. They have a bitter-astringent taste, and a faint but pleasant smell; yield their properties to water and alcohol; and will yield tannic and gallic acids; and resinous material. They are often adulterated with other leaves; but may be distinguished by their obovate or spathulate shape, leathery feeling, entire edges, and reticulated under-surface.

Properties and Uses: These leaves are principally astringent, with which they combine mild tonic and soothing properties. They increase the flow of urine; and while their powers are more or less expended upon all mucous membranes, they particularly show their influence upon the urino-genital structures. In chronic and sub-acute mucous discharges–such as catarrh of the bladder, leucorrhea, gonorrhea, and gleet–they serve an admirable purpose in lessening the discharge gradually, and giving tone to the parts. We have cured several cases of lingering gonorrhea, in females, with them alone; and have found them a valuable addition to the usual tonics, in leucorrhea. So, in aching of the kidneys and bladder, congestion and ulceration of the bladder and prostate gland, involuntary seminal emissions, and incontinence of urine, they serve a good purpose. They may be used in chronic diarrhea and dysentery; and are especially suited to an ulcerated condition of the bowels in such cases–when they may advantageously be combined with hydrastis. They are more grateful to the stomach than nearly any other astringent and give relief to the achings that usually accompany the above maladies. I have used them as a tonic and astringent in a bleeding stomach, bowels and kidneys, to very good advantage–being careful at the same time to distribute the blood to the surface. They are reputed good in diabetes, gravel and strangury, but of these connections I know nothing.

They unquestionably influence the uterus, and give tone to it. This action is of service in the treatment of leucorrhea, especially when connected with a flaccid condition of the womb and vagina, and with prolapsus. Also in parturition, when the parts are very moist and flaccid and the pains trifling, an infusion of the leaves will secure very positive uterine contractions. They also prepare the parts against flooding, under such conditions; and will be found of use in passive menorrhagia. As a parturient, they may be combined with some diffusive stimulant, as ginger or xanthoxylum. Dose, in powder, one to three scruples three times a day. They are seldom administered in this form, the decoction being preferable. Dr. M. S. Davenport, of Illinois, tells me he has used it as a local application to the bites of poisonous reptiles; and says it abstracts the poison, relieves the pain, and quiets nervous agitation.

Pharmaceutical Preparations: I. Decoction. One ounce of the leaves to a pint and a gill of water; simmer till a pint remains, or about fifteen minutes. Dose, two to three tablespoonfuls four times a day. In parturition, one tablespoonful, warm, every half hour. II. Extract. An alcoholic extract is a very good article, but that made on water is not so good. It may be given in pill, from three to six grains three times a day. III. Third Extract. This is a concentrated article, made as are the other preparations of this class. It may be given in doses of half to a whole teaspoonful, as desired; or may be added in suitable quantities to sirups. I employ this as a very valuable addition to the emulsion of copaiba, in the treatment of sub-acute gonorrhea–half an ounce of the extract in four ounces of emulsion; and to the compound sirup of mitchella in all gonorrheas. Like other astringents, the preparations of this article must not be made in vessels lined with iron.

Synonym: Arbutus uva-ursi

Description: Natural Order, Ericaceae. An evergreen shrub, of the heath family; common to the Northern parts of America, Europe, and Asia; preferring sandy and elevated positions. Stem prostrate, trailing, round, woody, several feet in length, covered with a deciduous bark; young branches erect, three to eight inches. Leaves, alternate, on short petioles, thick and leathery, entire, dark-green and smooth above, paler and veined beneath, obovate, half inch to an inch long. Flowers nearly white, tinted rose-pink; in short, terminal, drooping clusters. Calyx small, red, persistent; five-parted. Corolla ovoid, swollen at the base; with five small, reduced segments on the limb. Stamens ten, on the base of the corolla, with downy filament and red anthers. Fruit deep red, resembling a cranberry, nearly as large as a currant, tasteless, with five long and closely united seeds in the nucleus. Flowers June to September. Berries ripen during the winter.

The leaves of this plant are used in medicine. They have a bitter-astringent taste, and a faint but pleasant smell; yield their properties to water and alcohol; and will yield tannic and gallic acids; and resinous material. They are often adulterated with other leaves; but may be distinguished by their obovate or spathulate shape, leathery feeling, entire edges, and reticulated under-surface.

Properties and Uses: These leaves are principally astringent, with which they combine mild tonic and soothing properties. They increase the flow of urine; and while their powers are more or less expended upon all mucous membranes, they particularly show their influence upon the urino-genital structures. In chronic and sub-acute mucous discharges–such as catarrh of the bladder, leucorrhea, gonorrhea, and gleet–they serve an admirable purpose in lessening the discharge gradually, and giving tone to the parts. We have cured several cases of lingering gonorrhea, in females, with them alone; and have found them a valuable addition to the usual tonics, in leucorrhea. So, in aching of the kidneys and bladder, congestion and ulceration of the bladder and prostate gland, involuntary seminal emissions, and incontinence of urine, they serve a good purpose. They may be used in chronic diarrhea and dysentery; and are especially suited to an ulcerated condition of the bowels in such cases–when they may advantageously be combined with hydrastis. They are more grateful to the stomach than nearly any other astringent and give relief to the achings that usually accompany the above maladies. I have used them as a tonic and astringent in a bleeding stomach, bowels and kidneys, to very good advantage–being careful at the same time to distribute the blood to the surface. They are reputed good in diabetes, gravel and strangury, but of these connections I know nothing.

They unquestionably influence the uterus, and give tone to it. This action is of service in the treatment of leucorrhea, especially when connected with a flaccid condition of the womb and vagina, and with prolapsus. Also in parturition, when the parts are very moist and flaccid and the pains trifling, an infusion of the leaves will secure very positive uterine contractions. They also prepare the parts against flooding, under such conditions; and will be found of use in passive menorrhagia. As a parturient, they may be combined with some diffusive stimulant, as ginger or xanthoxylum. Dose, in powder, one to three scruples three times a day. They are seldom administered in this form, the decoction being preferable. Dr. M. S. Davenport, of Illinois, tells me he has used it as a local application to the bites of poisonous reptiles; and says it abstracts the poison, relieves the pain, and quiets nervous agitation.

Pharmaceutical Preparations: I. Decoction. One ounce of the leaves to a pint and a gill of water; simmer till a pint remains, or about fifteen minutes. Dose, two to three tablespoonfuls four times a day. In parturition, one tablespoonful, warm, every half hour. II. Extract. An alcoholic extract is a very good article, but that made on water is not so good. It may be given in pill, from three to six grains three times a day. III. Third Extract. This is a concentrated article, made as are the other preparations of this class. It may be given in doses of half to a whole teaspoonful, as desired; or may be added in suitable quantities to sirups. I employ this as a very valuable addition to the emulsion of copaiba, in the treatment of sub-acute gonorrhea–half an ounce of the extract in four ounces of emulsion; and to the compound sirup of mitchella in all gonorrheas. Like other astringents, the preparations of this article must not be made in vessels lined with iron.

Meriwether Lewis' Description, 29 Jan 28016

...the growth of high dry situations, and invariably in a piney country or on it's borders. It is generally found in the open piney woodland as on the Western side of the Rocky mountains, but in this neighbourhood we find it only in the prairies or on their borders in the more open wood lands.5 A very rich soil is not absolutely necessary, as a meager one frequently produces it abundantly.

The natives on this [the west] side of the Rocky mountains who can procure this berry invariably use it. To me it is a very tasteless and insippid fruit.

This shrub is an evergreen. The leaves retain their verdure most perfectly through the winter, even in the most rigid climate, as on lake Winnipic [Winnipeg].

The root of this shrub puts forth a great number of stems which separate near the surface of the ground, each stem from the size of a small quill to that of a man's finger. These are much more branched, the branches forming an acute angle with the stem, and all more properly procumbent than creeping, for altho' it sometimes puts forth radicles from the stem and branches which strike obliquely into the ground, these radicles are by no means general, nor equable in their distances from each other, nor do they appear to be calculated to furnish nutriment to the plant but rather to hold the stem or branch in its place.

The bark is formed of several thin layers of a smooth, thin, brittle substance of a dark or redish brown color, easily separated from the woody stem in flakes. The leaves with rispect to their position are scattered yet closely arranged near the extremities of the twigs particularly. The leaf is about three fourths of an inch in length and about half that in width, is oval but obtusely pointed, absolutely entire, thick, smooth, firm, a deep green and slightly grooved. The leaf is supported by a small footstalk of proportionable length.

The berry is attached in an irregular and scattered manner to the small boughs among the leaves, though frequently closely arranged, but always supported by separate short and small peduncles, the insertion of which produces a slight concavity in the bury while it's opposite side is slightly convex. The form of the berry is a spheroid, the shorter diameter being in a line with the peduncle.—This berry is a pericarp, the outer coat of which is a thin, firm, tough pellicle [outer skin]. The inner part consists of a dry mealy powder of a yellowish white color enveloping from four to six proportionably large, hard, light brown seeds, each in the form of a section of a spheroid, which figure they form when united, and are destitute of any membranous covering. The color of this [ripened] fruit is a fine scarlet.

The natives usually eat them without any preparation. The fruit ripens in September and remains on the bushes all winter. The frost appears to take no effect on it. These berries are sometimes gathered and hung in their lodges in bags where they dry without further trouble, for in their most succulent state they appear to be almost as dry as flour.

Note: Lewis also commented on 25 Jan 1806 that the the fruits were a staple food, eaten raw, cooked in salmon oil, bear fat, or with fish eggs, or added to soups and stews. They were also sometimes boiled and mixed with snow as a dessert. Lewis judged it "a very tasteless and insippid fruit," but added that it was sweeter after boiling. He noted on 11 April 1807, while in the Cascade mountains, that its flowers were in bloom.

The natives on this [the west] side of the Rocky mountains who can procure this berry invariably use it. To me it is a very tasteless and insippid fruit.