by Eric Yarnell, ND, RH(AHG)

Last updated 21 Apr 2023

This monograph is protected by copyright and is intended only for use by health care professionals and students. You may link to this page if you are sharing it with others in health care, but may not otherwise copy, alter, or share this material in any way. By accessing this material you agree to hold the author harmless for any use of this information.Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site.

Table of Contents

Clinical Highlights

Aconite is one of the most potent herbs in the entire materia medica, to used with great caution. Aconite overdose is potentially lethal due to arrhythmias.

At usual therapeutic doses, there are no adverse effects. Early signs of overdose include paresthesias, nausea, vertigo, and anxiety. Death can result from overdose.

Aconite, in very small doses, is a potent analgesic, febrifuge, and sedative.

Aconite is primarily used to control severe pain (especially neuropathic pain) and high fevers.

At usual therapeutic doses, there are no adverse effects. Early signs of overdose include paresthesias, nausea, vertigo, and anxiety. Death can result from overdose.

Aconite, in very small doses, is a potent analgesic, febrifuge, and sedative.

Aconite is primarily used to control severe pain (especially neuropathic pain) and high fevers.

Clinical Fundamentals

Part Used: The safest form of the herb is dried lateral root (as opposed to the main taproot) of Aconitum carmichaelii that has been decocted or cooked in some way to alter and deplete alkaloid levels. Higher doses are then required of this medicine to get clinical effects, though overdose is less likely to occur. It is also recommended roots be dried and processed of any other species.

Fresh root (or, much less commonly, flowering tops) has also been used to make tinctures, though far less of this should be used due to much higher alkaloid levels or relative lack of knowledge of which alkaloids are present and how they will act (Wang, et al. 2003a). Products made from unprocessed or fresh Sichuan aconite roots (川烏 chuān wū) and processed wild Sichuan aconite lateral roots (製草烏 zhì cǎo wū) are far more dangerous and should be avoided (or, if used, at extremely low doses).

Taste: Numbing, acrid

Major Actions:

Major Organ System Affinities

Major Indications:

In one open randomized trial, a combination of oral Chinese licorice and Sichuan aconite was as effective as diclofenac for reducing pain due to knee osteoarthritis (Deng 2008).

Major Constituents:

Fresh root (or, much less commonly, flowering tops) has also been used to make tinctures, though far less of this should be used due to much higher alkaloid levels or relative lack of knowledge of which alkaloids are present and how they will act (Wang, et al. 2003a). Products made from unprocessed or fresh Sichuan aconite roots (川烏 chuān wū) and processed wild Sichuan aconite lateral roots (製草烏 zhì cǎo wū) are far more dangerous and should be avoided (or, if used, at extremely low doses).

Taste: Numbing, acrid

Major Actions:

- Analgesic (Hikino, et al. 1979)

- Not a prostaglandin inhibitor (Murayama and Namiki 1989)

- Febrifuge, antipyretic (Hikino, et al. 1979)

- Sedative

Major Organ System Affinities

- Nervous system

Major Indications:

- Arthritis, topical and internal (Deng 2008)

- Fever, high or uncontrolled

- Headache, severe, non-migraine

- Neuralgia, topical and internal (Tai, et al. 2015)

- Posherpetic neuralgia (Nakanishi, et al. 2012)

- Pain, severe (Tai, et al. 2015)

- Cancer-related pain

- Neuropathic pain such as trigeminal neuralgia

In one open randomized trial, a combination of oral Chinese licorice and Sichuan aconite was as effective as diclofenac for reducing pain due to knee osteoarthritis (Deng 2008).

Major Constituents:

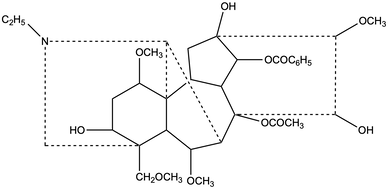

- Diterpenoid alkaloids (also called norditerpenoid alkaloids)

- Diester: most potent, but also unacceptably toxic

- Monoester: moderate potency with moderate but avoidable toxicity

- Alkylolamine (non-ester): low potency, non-toxic

- There are additional structural differences between various alkaloids that affect safety and activity. See the Advanced Clinical Information section for more information.

- Flavonoids (Braca, et al. 2003)

Adverse Effects: Though generally none occur at therapeutic doses, aconite can cause nausea, paresthesias and numbness of the mouth and lips (only if the medicine actually touches them; this doesn't occur with capsules), restlessness, or palpitations. See the overdose section below for more on this.

All aconite products should be kept out of reach of children and, ideally, in child-proof containers. They should be clearly marked as poisonous.

If palpitations occur, treatment should be immediately ceased and the patient closely monitored as these may be early signs of overdose.

The toxic effects of aconite are mediated through voltage-gated sodium channels, modulation of neurotransmitter release, lipid peroxidation, and induction of apoptosis of various cells (Fu, et al. 2006).

Contraindications:

Drug Interactions: Though there is little information from human studies on drug interactions, caution is warranted when combining aconite with proarrhythmic drugs and particularly those that prolong the QT interval (dofetilide, ibutilide, procainamide, quinidine, sotalol, fluoroquinolone antibiotics, ketoconazole, tricyclic antidepressants, fluoxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, antipsychotics, triptans, dolasetron, and methadone).

Herbal Incompatibilities: According to traditional Chinese medicine, Sichuan aconite is not to be combined with Bulbus Fritillariae, Rhizoma Pinelliae, Rhizoma Bletillae, Radix Ampelopsis, and Radix Trichosanthis.

Overdose: Note that patients who survive overdoses generally have no lasting negative effects (Tai, et al. 1992). In Hong Kong, there were 31 reported cases of aconite-associated poisonings at public hospitals and 2 patients died of ventricular arrhythmias from 1989–1991 (Chan 2002). After public awareness campaigns and media awareness increased, particularly about using unprocessed Sichuan aconite roots (川烏 chuān wū) and processed wild Sichuan aconite lateral roots (製草烏 zhì cǎo wū), herbalists seemed to use lower doses of these herbs and poisonings markedly decreased. A review of cases in mainland China found 53 deaths due to aconite use from 2004 to 2015, 77% of which were related to medicinal use of various aconite products and the rest from intentional or accidental ingestion of the roots as vegetables (Li, et al. 2016). Given the massive, widespread use of aconite in Chinese medicine, these rates of death are still extremely low, and do not suggest that appropriate, well-managed use of aconite clinically is significantly dangerous.

Signs of overdose:

See the Advanced Clinical Information section for overdose case reports.

All aconite products should be kept out of reach of children and, ideally, in child-proof containers. They should be clearly marked as poisonous.

If palpitations occur, treatment should be immediately ceased and the patient closely monitored as these may be early signs of overdose.

The toxic effects of aconite are mediated through voltage-gated sodium channels, modulation of neurotransmitter release, lipid peroxidation, and induction of apoptosis of various cells (Fu, et al. 2006).

Contraindications:

- Suicidal ideation

- Pregnancy

- Lactation

- Use caution in patients with arrhythmias.

Drug Interactions: Though there is little information from human studies on drug interactions, caution is warranted when combining aconite with proarrhythmic drugs and particularly those that prolong the QT interval (dofetilide, ibutilide, procainamide, quinidine, sotalol, fluoroquinolone antibiotics, ketoconazole, tricyclic antidepressants, fluoxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, antipsychotics, triptans, dolasetron, and methadone).

Herbal Incompatibilities: According to traditional Chinese medicine, Sichuan aconite is not to be combined with Bulbus Fritillariae, Rhizoma Pinelliae, Rhizoma Bletillae, Radix Ampelopsis, and Radix Trichosanthis.

Overdose: Note that patients who survive overdoses generally have no lasting negative effects (Tai, et al. 1992). In Hong Kong, there were 31 reported cases of aconite-associated poisonings at public hospitals and 2 patients died of ventricular arrhythmias from 1989–1991 (Chan 2002). After public awareness campaigns and media awareness increased, particularly about using unprocessed Sichuan aconite roots (川烏 chuān wū) and processed wild Sichuan aconite lateral roots (製草烏 zhì cǎo wū), herbalists seemed to use lower doses of these herbs and poisonings markedly decreased. A review of cases in mainland China found 53 deaths due to aconite use from 2004 to 2015, 77% of which were related to medicinal use of various aconite products and the rest from intentional or accidental ingestion of the roots as vegetables (Li, et al. 2016). Given the massive, widespread use of aconite in Chinese medicine, these rates of death are still extremely low, and do not suggest that appropriate, well-managed use of aconite clinically is significantly dangerous.

Signs of overdose:

- Neurological (>95% of patients experience these symptoms in Chan 2009)

- Paresthesias and numbness of limbs

- Weakness

- Tetraplegia (Chan, et al. 1994a)

- Anxiety

- Blurred vision

- Cardiovascular (~80% of patients experience these symptoms in Chan 2009)

- Hypotension

- Palpitations

- Chest pain

- Bradycardia

- Tachycardia (Tai, et al. 1992)

- Arrhythmias, including (Chan 2009):

- Ventricular ectopic beats

- Heart block

- Atrial fibrillation

- Ventricular arrhythmias (including torsade de pointes and fibrillation), potentially lethal (Imazio, et al. 2000)

- Gastrointestinal (50–75% of patients experience these symptoms in Chan 2009)

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Respiratory

- Decreased respiratory rate

- Respiratory paralysis, potentially lethal (Li, et al. 2016)

- In the case series of 13 Japanese patients with aconite overdose (9 attempting suicide, 4 accidental ingestion), all of them developed nausea, vomiting, tachyarrhythmias, hypotension, and chest pain (Terui, et al. 2008).

- Cases of suspected fatal anaphylaxis after exposure to very small doses of aconite have been reported, with petechial skin rashes and widespread eosinophilic infiltration of internal organs (Li, et al. 2016).

See the Advanced Clinical Information section for overdose case reports.

Treatment of Aconite Poisoning:

General

Antidotes for arrhythmias (Chan 2009):

Antidotes, other

Ineffective treatments

General

- Discontinue aconite intake.

- Keep patient still.

- Administer tannins or activated charcoal, or pump the stomach, after recent ingestion.

- Continuously monitor heart rhythms and blood pressure for 24 h after ingestion (Chan 2009)

- Avoid contact with an overdosed patient's vomitus, bodily fluids, aspirate, or any plant parts (Stetzenbach, et al. 2017).

Antidotes for arrhythmias (Chan 2009):

- Preferred: magnesium, flecainide and/or amiodarone (if tachycardic), atropine (if bradycardic)

- Magnesium: successful given intravenously, loading dose 1–6 g, may need to repeat 1–3 g per day for up to 3 days for recurrent symptoms (Clara, et al. 2015; Gottignies, et al. 2009; Weijters, et al. 2008; Moritz, et al. 2005)

- Class I anti-arrthymics (sodium channel blockers), most specific to aconite toxicity (which is characterized by persistent sodium channel activation):

- Class Ia agents: not recommended due to high risk of long QT syndrome

- Class Ib agents: lidocaine IV, mexiletene. Widely used but with poor efficacy (Lin, et al. 2004; Yeih, et al. 2000; Tai, et al. 1992). Relatively mild sodium channel blockers with some risk of shortening the QTc interval. NOT recommended.

- Class Ic agents: flecainide or propafenone. Experience is limited, but they are the most potent sodium channel blockers and do not affect the QT interval so should be safest.

- Class II anti-arrhythmics (autonomic effects):

- Class IIc: Atropine (used only if the patient is bradycardic or has heart block)

- Class III anti-arrthymics (potassium channel blockers, mostly shouldn't help):

- Amiodarone: mixed efficacy with limited clinical use (Sheth, et al. 2015; Chan 2009; Weijters, et al. 2008; Yeih, et al. 2000). A typical IV dose is 150 mg.

- This drug has mixed inhibitory effects on sodium, potassium, and calcium channels and is sympatholytic.

- The high iodine content in this drug runs the risk of exacerbating pre-existing hypothyroidism, or causing new-onset hypothyroidism.

- Bretylium: limited efficacy combined with other drugs with limited clinical use (Chan 2009), largely unavailable

- Amiodarone: mixed efficacy with limited clinical use (Sheth, et al. 2015; Chan 2009; Weijters, et al. 2008; Yeih, et al. 2000). A typical IV dose is 150 mg.

Antidotes, other

- Charcoal hemoperfusion reported helpful in very limited cases (Lin, et al. 2002)

- Ethanol and digitalis, onset slow, should only be used if modern medical facilities are not available (Felter 1922)

- Mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary bypass, and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in refractory cases (Chan 2009)

- Do NOT administer potassium (unless hypokalemic and considering using flecainide)

Ineffective treatments

- Calcium channel blockers

- Cardioversion (Chan 2009; Weijters, et al. 2008)

- Dialysis (Chan 2009)

Pharmacy Essentials

Critical notes on the importance of processing aconite:

Boiling aconite roots can reduce alkaloid content up to 90% (Chan and Critchley 1996). Cooking the roots changes diester diterpenoid alkaloids into lipoalkaloids and monoester alkaloids, thereby significantly reducing toxicity (Wang, et al. 2003b).

Though fresh aconite products can be used, albeit at very low doses, they are very much more risky than using processed ones. Therefore, only products made from the far better characterized and understood dried and cooked lateral roots are recommended.

Tincture of processed lateral root: The safest version of aconite is dried then decocted lateral roots, 1:3–1:5 w:v ratio, 30–45% ethanol. Note: if using a 1:10 w:v tincture, then the doses below should be doubled.

Dose:

Acute, adult: 3–5 gtt q2–3h, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, for no more than 3 days

Chronic, adult: 3–5 gtt tid

Child: not recommended

Glycerite: not recommended for use as you do not want to cover the taste or make this more appealing to children, and it is not clear if the alkaloids would extract well in this menstruum.

Decoction: 500–1,500 mg processed root per 250 ml water simmered for 1–2 h in a closed container; strain and drink 0.5–1 cup tid. Up to 6 g per day of processed lateral root is recommended in many Chinese herbal formula recipes.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup up to q2–3h for 1–2 days

Chronic, adult: 0.5–1 cup tid

Child: not recommended

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Boiling aconite roots can reduce alkaloid content up to 90% (Chan and Critchley 1996). Cooking the roots changes diester diterpenoid alkaloids into lipoalkaloids and monoester alkaloids, thereby significantly reducing toxicity (Wang, et al. 2003b).

Though fresh aconite products can be used, albeit at very low doses, they are very much more risky than using processed ones. Therefore, only products made from the far better characterized and understood dried and cooked lateral roots are recommended.

Tincture of processed lateral root: The safest version of aconite is dried then decocted lateral roots, 1:3–1:5 w:v ratio, 30–45% ethanol. Note: if using a 1:10 w:v tincture, then the doses below should be doubled.

Dose:

Acute, adult: 3–5 gtt q2–3h, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, for no more than 3 days

Chronic, adult: 3–5 gtt tid

Child: not recommended

Glycerite: not recommended for use as you do not want to cover the taste or make this more appealing to children, and it is not clear if the alkaloids would extract well in this menstruum.

Decoction: 500–1,500 mg processed root per 250 ml water simmered for 1–2 h in a closed container; strain and drink 0.5–1 cup tid. Up to 6 g per day of processed lateral root is recommended in many Chinese herbal formula recipes.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup up to q2–3h for 1–2 days

Chronic, adult: 0.5–1 cup tid

Child: not recommended

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Other Names

Latin synonyms:

Current correct Latin binomial: Aconitum carmichaelii Debeaux

Aconitum bodinieri H Lév & Vaniot

Aconitum jiulongense WT Wang

Aconitum kusnezoffii var bodinieri (H Lév & Vaniot) Finet & Gagnep

Aconitum lushanense Migo

Aconitum wilsonii Stapf ex Mottet

English Common Names: Sichuan aconite, Chinese aconite

Asian Common Names: see table

Current correct Latin binomial: Aconitum carmichaelii Debeaux

Aconitum bodinieri H Lév & Vaniot

Aconitum jiulongense WT Wang

Aconitum kusnezoffii var bodinieri (H Lév & Vaniot) Finet & Gagnep

Aconitum lushanense Migo

Aconitum wilsonii Stapf ex Mottet

English Common Names: Sichuan aconite, Chinese aconite

Asian Common Names: see table

| Product | Chinese (Mandarin) | Japanese | Korean |

| A. carmichaelii processed lateral root (only form recommended for use) | 附子 fù zǐ ("appendage") | shuchi-bushi-matsu | |

| A. carmichaelii prepared main root | 川烏 chuān wū ("Sichuan crow's head") | ||

| A. carmichaelii plant | 烏頭 (traditional), 乌头 (simplified) wū tóu ("raven/black head") | bushi | puja, buja |

| A. kusnezoffii prepared lateral root | 製草烏 zhì cǎo wū ("prepared black grass") | ||

| A. kusnezoffii fresh root | 草烏 cǎo wū ("black grass") | ||

Latin synonyms:

Current correct Latin binomial: Acontium napellus L

Aconitum ampliflorum Rchb

Aconitum anglicum Stapf

Aconitum confertum Rchb

Aconitum fornicatum Gilib

Aconitum funckii Rchb

Aconitum grandiflorum Pall

Aconitum halleri Rchb

Aconitum microstachyum Rchb

Aconitum neubergense DC

Aconitum spicatum Donn

Aconitum venustum Rchb

Aconitum willdenowii Rchb

Delphinium napellus Baill

Napellus vulgaris Fourr

English common names: monkshood, monks-hood, monk’s-hood, monk's blood, monk's hood (all referring to shape of the flower), aconite, auld wife's huid, bear's-foot, blue rocket, European blue-monkshood, friar's cap, garden monk's-hood, garden monkshood, helmet flower, Turk's-cap, Venus' chariot, wolf's bane, wolfsbane, devil's helmet

Albanian common name: spineri

Arabic common names: بيش, قاتل النمر, هلهل

Azerbaijani common name: turpabənzər kəpənəkçiçəyi

Basque common name: irabelar

Catalan common names: acònit blau, escanyallops, herba tora, herba verinosa, matallops blau, siuet o sivet, tora, tora blava, xiuet

Czech common name: oměj šalamounek

Danish common names: blå stormhat, blå venusvogn, stormhat, venusvogn, ægte stormhat ægte stormhat ægte stormhat, ægte stormhat

Dutch common names: blauwe monnikskap, duivelskruid, monnikskap, monnikskapsoort, gewone akoniet

Esperanto common names: blua akonito, akonito blua, akonito napela, kaskofloro blua

Estonian common name: sinine käoking

Finnish common names: ukonhattu, aitoukonhattu

French common names: aconit napel, capuchon-de-moine, casque bleu, casque de jupiter, char de vénus, napel

German common names: blauer Eisenhut, blaue Mönchskappe, echter Eisenhut, echter Sturmhut, Eisenhut, Fischerkappe, Fuchswurz, Gifthut, Giftkraut, Mönchshut, Reiterkappe, Sturmhut, Tübeli, Venuswagen, Wolfskraut, Wolfswurz, Würgling, Ziegentod

Hungarian common names: havasi sisakvirág, kék sisakvirág

Icelandic common names: bláhjálmur, venusarvagn, venusvagn

Irish common name: dáthabha, dáthabha-dubh

Italian common names: aconito napello, aconitum napellus, erba luparia

Kurdish common name: çirnûkê gur

Latvian common name: zilā kurpīte

Lithuanian common name: mėlynoji kurpelė

Malayalam common name: വത്സനാഭി

Nepali common name: madhu bikh

Norwegian common names: storhjelm , venusvogn

Persian common name: اقونیطون

Polish common names: tojad mocny, tojad, tojam mocny

Portuguese common name: acônito (continental and Brazilian)

Russian common names: боре́ц клобучко́вый, аконит, акони́т клобучко́вый, борец клобучковый, садовый аконит

Scottish Gaelic common names: currac-sagairt, currac-manaich, flùr an t-sagairt, tàthabha (generic term for many poisonous plants), fuath-mhadaidh, fuath a' mhadaidh, tàthabha-dubh

Slovak common name: prilbica modrá

Slovenian common names: preobjeda repičasta, repičasta preobjeda

Spanish common names: acónito común, acónito, aconitum napellus, acotnito, anapelo, matalobos, nabillo del diablo, napelo

Swedish common name: äkta stormhatt

Turkish common names: boğanotu, kaplanboğanotu, migferotu

Welsh common names: cwcwll y mynach, bleidd-dag, cwfl y mynach, llysiau'r blaidd

Aconite is derived from the Greek name for the plant, ἀκόνιτον (akóniton). This literally means, "without struggle or without dust" (κόνις = dust). It may be derived from the ancient name of the city of Acona in Turkey, related to the Greek word akona, "rock," possibly related to the predilection of the herb for growing near rocky hills and mountains (Benigni et al. 1971). It was Latinized as Aconitum. The species name napellus is <Latin and means "small turnip," describing the shape of the root. The species name carmichaelii is after J. R. Carmichael (1838–1870), an English physician and plant collector who also worked as a Christian missionary in China. The species name kusnezoffii is after Russian botanist Nikolai Kuznetsov (1864–1932).

Latin synonyms:

Current correct Latin binomial: Aconitum columbianum Nutt

Aconitum arizonicum Greene

Aconitum bakeri Greene

Aconitum geranioides Greene

Aconitum glaberrimum Rydb

Aconitum leibergii Greene

Aconitum lutescens A Nelson

Aconitum macilentum Greene

Aconitum mogollonicum Greene

Aconitum nivatum A Nelson

Aconitum obtusiflorum Greene

Aconitum ochroleucum Rydb

Aconitum oregonsense Raf

Aconitum patens Rydb

Aconitum platysepalum Greene

Aconitum porrectum Rydb

Aconitum ramosum A Nelson

Aconitum robertianum Greene

Aconitum subcaesium Greene

Aconitum tricorne Greene

Aconitum vestitum Greene

Native American Common Names: none identified

Current correct Latin binomial: Acontium napellus L

Aconitum ampliflorum Rchb

Aconitum anglicum Stapf

Aconitum confertum Rchb

Aconitum fornicatum Gilib

Aconitum funckii Rchb

Aconitum grandiflorum Pall

Aconitum halleri Rchb

Aconitum microstachyum Rchb

Aconitum neubergense DC

Aconitum spicatum Donn

Aconitum venustum Rchb

Aconitum willdenowii Rchb

Delphinium napellus Baill

Napellus vulgaris Fourr

English common names: monkshood, monks-hood, monk’s-hood, monk's blood, monk's hood (all referring to shape of the flower), aconite, auld wife's huid, bear's-foot, blue rocket, European blue-monkshood, friar's cap, garden monk's-hood, garden monkshood, helmet flower, Turk's-cap, Venus' chariot, wolf's bane, wolfsbane, devil's helmet

Albanian common name: spineri

Arabic common names: بيش, قاتل النمر, هلهل

Azerbaijani common name: turpabənzər kəpənəkçiçəyi

Basque common name: irabelar

Catalan common names: acònit blau, escanyallops, herba tora, herba verinosa, matallops blau, siuet o sivet, tora, tora blava, xiuet

Czech common name: oměj šalamounek

Danish common names: blå stormhat, blå venusvogn, stormhat, venusvogn, ægte stormhat ægte stormhat ægte stormhat, ægte stormhat

Dutch common names: blauwe monnikskap, duivelskruid, monnikskap, monnikskapsoort, gewone akoniet

Esperanto common names: blua akonito, akonito blua, akonito napela, kaskofloro blua

Estonian common name: sinine käoking

Finnish common names: ukonhattu, aitoukonhattu

French common names: aconit napel, capuchon-de-moine, casque bleu, casque de jupiter, char de vénus, napel

German common names: blauer Eisenhut, blaue Mönchskappe, echter Eisenhut, echter Sturmhut, Eisenhut, Fischerkappe, Fuchswurz, Gifthut, Giftkraut, Mönchshut, Reiterkappe, Sturmhut, Tübeli, Venuswagen, Wolfskraut, Wolfswurz, Würgling, Ziegentod

Hungarian common names: havasi sisakvirág, kék sisakvirág

Icelandic common names: bláhjálmur, venusarvagn, venusvagn

Irish common name: dáthabha, dáthabha-dubh

Italian common names: aconito napello, aconitum napellus, erba luparia

Kurdish common name: çirnûkê gur

Latvian common name: zilā kurpīte

Lithuanian common name: mėlynoji kurpelė

Malayalam common name: വത്സനാഭി

Nepali common name: madhu bikh

Norwegian common names: storhjelm , venusvogn

Persian common name: اقونیطون

Polish common names: tojad mocny, tojad, tojam mocny

Portuguese common name: acônito (continental and Brazilian)

Russian common names: боре́ц клобучко́вый, аконит, акони́т клобучко́вый, борец клобучковый, садовый аконит

Scottish Gaelic common names: currac-sagairt, currac-manaich, flùr an t-sagairt, tàthabha (generic term for many poisonous plants), fuath-mhadaidh, fuath a' mhadaidh, tàthabha-dubh

Slovak common name: prilbica modrá

Slovenian common names: preobjeda repičasta, repičasta preobjeda

Spanish common names: acónito común, acónito, aconitum napellus, acotnito, anapelo, matalobos, nabillo del diablo, napelo

Swedish common name: äkta stormhatt

Turkish common names: boğanotu, kaplanboğanotu, migferotu

Welsh common names: cwcwll y mynach, bleidd-dag, cwfl y mynach, llysiau'r blaidd

Aconite is derived from the Greek name for the plant, ἀκόνιτον (akóniton). This literally means, "without struggle or without dust" (κόνις = dust). It may be derived from the ancient name of the city of Acona in Turkey, related to the Greek word akona, "rock," possibly related to the predilection of the herb for growing near rocky hills and mountains (Benigni et al. 1971). It was Latinized as Aconitum. The species name napellus is <Latin and means "small turnip," describing the shape of the root. The species name carmichaelii is after J. R. Carmichael (1838–1870), an English physician and plant collector who also worked as a Christian missionary in China. The species name kusnezoffii is after Russian botanist Nikolai Kuznetsov (1864–1932).

Latin synonyms:

Current correct Latin binomial: Aconitum columbianum Nutt

Aconitum arizonicum Greene

Aconitum bakeri Greene

Aconitum geranioides Greene

Aconitum glaberrimum Rydb

Aconitum leibergii Greene

Aconitum lutescens A Nelson

Aconitum macilentum Greene

Aconitum mogollonicum Greene

Aconitum nivatum A Nelson

Aconitum obtusiflorum Greene

Aconitum ochroleucum Rydb

Aconitum oregonsense Raf

Aconitum patens Rydb

Aconitum platysepalum Greene

Aconitum porrectum Rydb

Aconitum ramosum A Nelson

Aconitum robertianum Greene

Aconitum subcaesium Greene

Aconitum tricorne Greene

Aconitum vestitum Greene

Native American Common Names: none identified

Interchangeability of Species

Many, probably all, aconite species are medicinal, with varying degrees of potency and potential toxicity. The best understood of all these species is Aconitum carmichaelii. It has a long record of use in traditional Asian medicine, and in particular is the basis of the knowing that cooked lateral roots are much safer to use than fresh or dried lateral or main roots. Overall, there is much better, clearer scientific and traditional information about this species, making it the primary species recommended for use.

A. kusnezoffii has also been used in traditional Asian medicine, though it is considered much more potent and thus toxic than A. carmichaelii. Its use is not recommended.

The standard species used in Europe is A. napellus. Information about it is much less clear, though fairly abundant, and so it is considered at best a second-tier choice after A. carmichaelii.

Aconitum columbianum, native to the mountains of the Pacific Northwest, is also available and is moderately less potent than A. napellus. Again, due to severe lack of clear information, this species is not recommended for use.

A. kusnezoffii has also been used in traditional Asian medicine, though it is considered much more potent and thus toxic than A. carmichaelii. Its use is not recommended.

The standard species used in Europe is A. napellus. Information about it is much less clear, though fairly abundant, and so it is considered at best a second-tier choice after A. carmichaelii.

Aconitum columbianum, native to the mountains of the Pacific Northwest, is also available and is moderately less potent than A. napellus. Again, due to severe lack of clear information, this species is not recommended for use.

Advanced Clinical Information

Additional Actions:

In rats, the Sichuan aconite portion of the formula gosha-jinki-gan decreased bladder sensation by stimulating κ-opioid receptors, and did not affect bladder contractility and thus force of the urine stream (Gotoh, et al. 2004).

Diterpenoid alkaloids from aconite are believed to act primarily by activating sodium channels in excitable cells, notably neurons, cardiac myocytes, and skeletal myocytes, thereby inhibiting repolarization (Jouglard et al, 1977). This tends to induce excessive parasympathetic activity, which can cause nausea, vomiting, paresthesias, hypotension, and bradycardia. However, many other complex actions of these compounds on alpha-adrenergic and other receptors have been demonstrated (Isono, et al. 1994).

Additional Indications:

Herbalist Michael Moore has utilized processed root tincture of western aconite to help some people withdraw from amphetamines and cocaine. He has also used this product for treating people with chronic allergies not responding to other treatments.

A human trial has shown that fu zi increases nitric oxide production, perhaps leading to vasodilation and explaining its use for "cold" syndromes with poor cirulation in traditional Asian medicine (Yamada, et al. 2005). This herb is traditionally considered the hottest herb in Chinese medicine.

Allapinin (allapinine) is a semi-synthetic derivative of the diterpenoid alkaloid aconitine developed in Russia. It has been used successfully to treat various types of arrhythmias in clinical trials, such as atrial fibrillation (Kadyrova, et al. 1990).

Intravenous injection of 100 ml of a solution containing 800 mcg ginsenoside and 1.8 mcg aconitine per ml, mixed with 500 ml of 5% glucose (known as shenfu injection), into patients with aplastic anemia, along with stanozol and cyclosporin A, was not significantly different than stanozol and cyclosporin A alone in treating patients with aplastic anemia (Wang, et al. 2005).

In several places in China, A. carmichaelii roots are actually consumed as a root vegetable (Kang, et al. 2012). In all documented cases, it is cooked for a very long time, until any mouth- or tongue-numbing properties are lost.

Advanced Chemistry:

Maximum allowed diester alkaloid content in aconite in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia is 0.01%.

Monoester alkaloids are 100 times less toxic and less potent than diester alkaloids (Singhuber, et al. 2009; Wada, et al. 2005).

Alkylolamines (non-ester) alkaloids are essentially non-toxic but also inactive (Singhuber, et al. 2009; Wada, et al. 2005).

Those aconite diterpenoid alkaloids with aroyloxy group at R4 position (and of significantly lower molecular weight), including N-deacetyllappaconitine, lappaconitine, ranaconitine, N-deacetylfinaconitine, and N-deacetylranaconitine, were far less toxic yet still significantly anesthetic compared to alkaloids with an aroyl/aroyloxy group at the R14 position, including yunaconitine, bulleyaconitine, aconitine, beiwutine, nagarine, 3-acetyl aconitine, and penduline (Bello-Ramirez and Nava-Ocampo 2004).

Overdose Case Reports:

A 21-year-old French man took 3 caps with 237 mg root (containing 19 mcg aconitine in total) to sleep. He awoke in 5 h with general paresthesia, nausea, diarrhea, vertigo, dyspnea, chest pain, and dyschromatopsia (disrupted color vision). He went to the emergency room 7 h after ingestion, and was shown to have bradycardia with ventricular arrhythmia. He was treated with 1 g intravenous magnesium. Within 13 h all cardiovascular and neurological symptoms cleared (Moritz, et al. 2005).

A healthy 25-year-old Canadian man ate some Aconitum napellus flowers (believed to be a case of mistaken plant identification) while hiking on an uninhabited island off the coast of Newfoundland. Approximately 2.5 h later he developed nausea and abdominal pain, and 30 min after that he vomited. Approximately 45 min later he suddenly collapsed and could not be resuscitated, consistent with ventricular arrhythmia (though this could not be formally diagnosed). Necropsy revealed cyanotic nail beds, severe congestion of all internal organs, and severe intrapulmonary bleeding and edema. His postmortem blood level of aconitine was 3.6 mcg/L with a urine level of 149 mcg/L (Pullela, et al. 2008).

A previously healthy 39-year-old Dutch man ate a homemade salad of wild greens (mistaking Aconitum napellus for celery) and developed sweating, paresthesias in his tongue and hands, nausea, vomiting, and severe diarrhea (Weijters, et al. 2008). He had profound hypotension and ventricular tachycardia (heart rate 220 beats/min). Several attempts at cardioversion were unsuccessful and he progressed to ventricular fibrillation and required resuscitation with intravenous epinephrine, magnesium 5 g, and amiodarone 450 mg. Within 12 h he had completely recovered.

In rats, the Sichuan aconite portion of the formula gosha-jinki-gan decreased bladder sensation by stimulating κ-opioid receptors, and did not affect bladder contractility and thus force of the urine stream (Gotoh, et al. 2004).

Diterpenoid alkaloids from aconite are believed to act primarily by activating sodium channels in excitable cells, notably neurons, cardiac myocytes, and skeletal myocytes, thereby inhibiting repolarization (Jouglard et al, 1977). This tends to induce excessive parasympathetic activity, which can cause nausea, vomiting, paresthesias, hypotension, and bradycardia. However, many other complex actions of these compounds on alpha-adrenergic and other receptors have been demonstrated (Isono, et al. 1994).

Additional Indications:

- Amphetamine or cocaine withdrawal

- Allergies, chronic

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- Cold syndromes (Yamada, et al. 2005)

- Congestive heart failure (Yang, et al. 2019)

Herbalist Michael Moore has utilized processed root tincture of western aconite to help some people withdraw from amphetamines and cocaine. He has also used this product for treating people with chronic allergies not responding to other treatments.

A human trial has shown that fu zi increases nitric oxide production, perhaps leading to vasodilation and explaining its use for "cold" syndromes with poor cirulation in traditional Asian medicine (Yamada, et al. 2005). This herb is traditionally considered the hottest herb in Chinese medicine.

Allapinin (allapinine) is a semi-synthetic derivative of the diterpenoid alkaloid aconitine developed in Russia. It has been used successfully to treat various types of arrhythmias in clinical trials, such as atrial fibrillation (Kadyrova, et al. 1990).

Intravenous injection of 100 ml of a solution containing 800 mcg ginsenoside and 1.8 mcg aconitine per ml, mixed with 500 ml of 5% glucose (known as shenfu injection), into patients with aplastic anemia, along with stanozol and cyclosporin A, was not significantly different than stanozol and cyclosporin A alone in treating patients with aplastic anemia (Wang, et al. 2005).

In several places in China, A. carmichaelii roots are actually consumed as a root vegetable (Kang, et al. 2012). In all documented cases, it is cooked for a very long time, until any mouth- or tongue-numbing properties are lost.

Advanced Chemistry:

Maximum allowed diester alkaloid content in aconite in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia is 0.01%.

Monoester alkaloids are 100 times less toxic and less potent than diester alkaloids (Singhuber, et al. 2009; Wada, et al. 2005).

Alkylolamines (non-ester) alkaloids are essentially non-toxic but also inactive (Singhuber, et al. 2009; Wada, et al. 2005).

Those aconite diterpenoid alkaloids with aroyloxy group at R4 position (and of significantly lower molecular weight), including N-deacetyllappaconitine, lappaconitine, ranaconitine, N-deacetylfinaconitine, and N-deacetylranaconitine, were far less toxic yet still significantly anesthetic compared to alkaloids with an aroyl/aroyloxy group at the R14 position, including yunaconitine, bulleyaconitine, aconitine, beiwutine, nagarine, 3-acetyl aconitine, and penduline (Bello-Ramirez and Nava-Ocampo 2004).

Overdose Case Reports:

A 21-year-old French man took 3 caps with 237 mg root (containing 19 mcg aconitine in total) to sleep. He awoke in 5 h with general paresthesia, nausea, diarrhea, vertigo, dyspnea, chest pain, and dyschromatopsia (disrupted color vision). He went to the emergency room 7 h after ingestion, and was shown to have bradycardia with ventricular arrhythmia. He was treated with 1 g intravenous magnesium. Within 13 h all cardiovascular and neurological symptoms cleared (Moritz, et al. 2005).

A healthy 25-year-old Canadian man ate some Aconitum napellus flowers (believed to be a case of mistaken plant identification) while hiking on an uninhabited island off the coast of Newfoundland. Approximately 2.5 h later he developed nausea and abdominal pain, and 30 min after that he vomited. Approximately 45 min later he suddenly collapsed and could not be resuscitated, consistent with ventricular arrhythmia (though this could not be formally diagnosed). Necropsy revealed cyanotic nail beds, severe congestion of all internal organs, and severe intrapulmonary bleeding and edema. His postmortem blood level of aconitine was 3.6 mcg/L with a urine level of 149 mcg/L (Pullela, et al. 2008).

A previously healthy 39-year-old Dutch man ate a homemade salad of wild greens (mistaking Aconitum napellus for celery) and developed sweating, paresthesias in his tongue and hands, nausea, vomiting, and severe diarrhea (Weijters, et al. 2008). He had profound hypotension and ventricular tachycardia (heart rate 220 beats/min). Several attempts at cardioversion were unsuccessful and he progressed to ventricular fibrillation and required resuscitation with intravenous epinephrine, magnesium 5 g, and amiodarone 450 mg. Within 12 h he had completely recovered.

Classic Formulas

Fu zi is a part of numerous traditional Chinese herbal formulas. A small sampling is provided here.

右歸丸 (simplified: 右归丸)

Yòu Guī Wán, Restore the Right (Kidney) Pill

Rehmannia glutinosa (熟地黃 shú dì huáng, rehmannia) cooked root

Aconitum carmichaeli (製附子 zhì fù zǐ, Sichuan aconite) prepared lateral root

Cinnamomum cassia (肉桂 ròu guì, cinnamon) bark

Dioscorea oppositifolia (山藥 shān yào, Chinese yam) rhizome

Cuscuta chinensis (菟絲子 tù sī zǐ, dodder) seed

Cervus nippon (鹿茸 lù róng, deer antler velvet), unsustainable and cruel, substitute Panax ginseng or more Eucomma ulmoides

Lycium chinense (枸杞子 gǒu qǐ zǐ, goji) fruit

Eucommia ulmoides (杜仲 dù zhòng, eucommia) bark

Cornus officinalis (山茱萸 shān zhū yú, Asiatic Cornelian cherry) fruit

Angelica sinensis (當歸 dāng guī, dong quai) root

Origin: Collected Treatises of [Zhang] Jing-Yue, 1624 (variant of 腎氣丸 shèn qì wán, Kidney Qi Pill)

Traditional actions: warms/tonifies Kidney yang, replenishes Jing, tonifies Blood and Marrow

Indications: hypothyroidism (modified version proved effective in one case series, Li, et al. 1998). It is also appropriate for some patients with infertility due to low sperm count, nephrotic syndrome, allergic asthma (Hsu, et al. 2021; Zhang, et al. 2015; Lin, et al. 2012), anemia (many types), osteoporosis (Li, et al. 2018), and low white blood cell counts.

芍藥甘草附子湯 (simplified: 芍药甘草附子汤)

Sháo Yào Gān Cǎo Fù Zǐ Tāng (Peony, Licorice and Aconite Decoction)

Paeonia lactiflora (芍藥 sháo yào, white peony) root without bark

Glycyrrhiza uralensis (甘草 gān cǎo, Chinese licorice) root

Aconitum carmichaeli} (製附子 zhì fù zǐ, Sichuan aconite) prepared lateral root

Origin: Discussion of Cold Damage, 220

Traditional actions: support Yang, benefit Yin

Indications: use of this formula in patients with rheumatoid arthritis was associated with reduced risk of stroke in one retrospective analysis (Lai, et al. 2019).

Synergy: Chinese licorice, particularly its constituent glycyrrhizin, improves absorption of Sichuan aconite and decreases its toxicity (Chen, et al. 2009; Shen, et al. 2011). White peony's compound paeoniflorin also protected mice against aconite toxicity, in part by altering the pharmacokinetics of aconite's alkaloids (Fan, et al. 2012).

右歸丸 (simplified: 右归丸)

Yòu Guī Wán, Restore the Right (Kidney) Pill

Rehmannia glutinosa (熟地黃 shú dì huáng, rehmannia) cooked root

Aconitum carmichaeli (製附子 zhì fù zǐ, Sichuan aconite) prepared lateral root

Cinnamomum cassia (肉桂 ròu guì, cinnamon) bark

Dioscorea oppositifolia (山藥 shān yào, Chinese yam) rhizome

Cuscuta chinensis (菟絲子 tù sī zǐ, dodder) seed

Cervus nippon (鹿茸 lù róng, deer antler velvet), unsustainable and cruel, substitute Panax ginseng or more Eucomma ulmoides

Lycium chinense (枸杞子 gǒu qǐ zǐ, goji) fruit

Eucommia ulmoides (杜仲 dù zhòng, eucommia) bark

Cornus officinalis (山茱萸 shān zhū yú, Asiatic Cornelian cherry) fruit

Angelica sinensis (當歸 dāng guī, dong quai) root

Origin: Collected Treatises of [Zhang] Jing-Yue, 1624 (variant of 腎氣丸 shèn qì wán, Kidney Qi Pill)

Traditional actions: warms/tonifies Kidney yang, replenishes Jing, tonifies Blood and Marrow

Indications: hypothyroidism (modified version proved effective in one case series, Li, et al. 1998). It is also appropriate for some patients with infertility due to low sperm count, nephrotic syndrome, allergic asthma (Hsu, et al. 2021; Zhang, et al. 2015; Lin, et al. 2012), anemia (many types), osteoporosis (Li, et al. 2018), and low white blood cell counts.

芍藥甘草附子湯 (simplified: 芍药甘草附子汤)

Sháo Yào Gān Cǎo Fù Zǐ Tāng (Peony, Licorice and Aconite Decoction)

Paeonia lactiflora (芍藥 sháo yào, white peony) root without bark

Glycyrrhiza uralensis (甘草 gān cǎo, Chinese licorice) root

Aconitum carmichaeli} (製附子 zhì fù zǐ, Sichuan aconite) prepared lateral root

Origin: Discussion of Cold Damage, 220

Traditional actions: support Yang, benefit Yin

Indications: use of this formula in patients with rheumatoid arthritis was associated with reduced risk of stroke in one retrospective analysis (Lai, et al. 2019).

Synergy: Chinese licorice, particularly its constituent glycyrrhizin, improves absorption of Sichuan aconite and decreases its toxicity (Chen, et al. 2009; Shen, et al. 2011). White peony's compound paeoniflorin also protected mice against aconite toxicity, in part by altering the pharmacokinetics of aconite's alkaloids (Fan, et al. 2012).

Monograph from Eclectic Materia Medica (Felter 1922)

ACONITUM NAPELLUS

The dried tuberous root of Aconitum napellus, Linné (Nat. Ord. Ranunculaceae). Mountains of Europe and Asia, and northwestern North America. Dose (maximum), 1 grain.

Common Names: Aconite, Monkshood, Wolfsbane.

Principal Constituents.–Aconitine (C34H47O11N) one of the most poisonous of known alkaloids, occurring as permanent colorless or white crystals, without odor. A drop of solution of one part of aconitine in 100,000 of water will produce the characteristic tingling and benumbing sensation of aconite. The alkaloid itself must never be tasted, and the solution only when extremely diluted, and then with the greatest of caution. Aconitine is soluble in alcohol, ether, and benzene; very slightly in water. Other constituents of Aconite are aconine and benzaconine, both alkaloids; the former of little activity; the latter a strong heart depressant.

Commercial Aconitine is a more or less impure mixture of aconite alkaloids.

Preparations.–1. Specific Medicine Aconite. An exceedingly poisonous and representative preparation. Dose, 1/30 to 1/2 drop. (Usual form of administration: Rx Specific Medicine Aconite 1-10 drops: Water 4 fluidounces. Mix. Sig. One teaspoonful every one-half (1/2) to two (2) hours.)

2. Tinctura Aconiti, Tincture of Aconite (10 per cent aconite). Dose, 1 to 8 minims.

Note.—Fleming's Tincture of Aconite is many times stronger than the preceding, with which it should not be confounded. It should have no place in modern therapeutics.

Specific Indications.–The small and frequent pulse, whether corded or compressible, with either elevated or depressed temperature and not due to sepsis, is the most direct indication. Irritation of mucous membranes with vascular excitation and determination of blood; hyperemia; chilly sensations; skin hot and dry, with small, frequent pulse. Early stage of fevers with or without restlessness. When septic processes prevail it is only relatively indicated.

Action.–The effects of aconite, considered from the so-called physiological action, are expressed in local and general irritation followed by tingling, numbness, and peripheral sensory paralysis, primarily reduced force and frequency of the heart action, due to vagal stimulation, and subsequent rapid pulse, due to vagal depression. The heart muscle is also thought to be paralyzed by it. The action upon the vaso-motor system is not well understood, though the lowered arterial pressure is explained by some as due to depression of the vaso-motor center. In small doses aconite quiets hurried breathing, but large doses may cause death through respiratory paralysis. Temperature is lowered by aconite, probably by increase of heat-dissipation and possibly through the action of the thermo-genetic system. This action is most pronounced during fevers. Except of the skin and kidneys, the glands of the body seem to be but little, if at all, affected by aconite. The kidney function is slightly increased, while that of the skin is markedly influenced according to the quantity administered. The motor nervous system is not noticeably affected except when poisonous doses are given, but the sensory nerves, especially at the periphery, are notably impressed by even so-called therapeutic doses. It is quite clear that aconite does not act strongly upon the cerebrum, except that poisonous doses somewhat depress the perceptive faculty. Upon the skin and mucous surfaces it acts first as an irritant, then as an anaesthetic. The mode of elimination of aconite is not yet well determined, but it is thought that it is largely oxidized, thus accounting for the short duration of its action. Indeed, the systemic effects of aconite seldom last over three hours, though the therapeutic result may be permanent. When aconite kills it does so usually by paralyzing the heart, arresting that organ in diastole.

Locally, aconite and its alkaloid, aconitine, act as irritants, producing a tingling, pricking sensation and numbness, followed by peripheral sensory impairment, resulting in anaesthesia of the part. The latter is due to paralysis of the sensory nerve terminals. Usually no redness nor inflammation follows, but in rarely susceptible cases vesicular or pustular eruptions take place, or intense cutaneous itching. Both are extremely irritating to the nasal and ocular membranes, and when inhaled may give rise to a peculiar local sense of icy-coldness.

Administered internally in small doses aconite occasions a tingling or prickling sensation, felt first in the mouth, tongue, and fauces, and quickly extending to the stomach. This is rapidly followed by more or less numbness. Gastric warmth and a general glow of the surface follow non-lethal doses. Slight perspiration may be induced, but sweating to any great degree does not take place except from large doses. Then it is an almost constant symptom. Temperature is reduced, but the more readily during pyrexia, when the pulse is frequent and small, if the dose administered be fractional.

In maximum doses (by some called full therapeutic doses) aconite causes gastric heat. A sense of warmth throughout the system follows, and occasionally the thrilling or tingling sensation will be more generally experienced, with perhaps some numbness. There may be dizziness most marked upon assuming the upright posture, pain in the head, acute body pain, excessive depression, with feeble circulation and diminished respiration. The pulse may fall to 30 or 40 beats per minute and muscular weakness become extreme. Eclectic teaching has long protested against giving aconite in doses sufficient to produce these effects, which some, with extreme boldness, declare to be therapeutic results.

Toxicology.–In poisonous amounts the symptoms given are exaggerated and the effects extremely rapid. Tingling and numbness increase and are felt all over the body, the thrilling and creeping coldness approaching from the extremities to the body. Excessive sweating comes on, rapidly lowering the body temperature, dimness of vision, loss of hearing and touch, and general peripheral paralysis extending from the extremities to the trunk. The victim is conscious of danger, feels cold and is extremely anxious and prostrated. Muscular weakness is pronounced, tremors occur, and rarely convulsions. The power of standing is lost early. The face is extremely pale, the sclerotics pearly, eyes sunken, the countenance one of extreme anxiety, and there is a tendency to fainting. There may be gastric pain and vomiting. If the recumbent position is not maintained, or even if slight exertion be attempted, sudden death may occur from syncope. Unless consciousness be lost through syncope, the intellect remains unimpaired until just before death, showing that aconite probably does not greatly impress the cerebrum.

The one diagnostic symptom of aconite poisoning is the characteristic aconite tingling. If confession (in case of attempted suicide) is not forthcoming or the patient is unable to reveal the fact that poison has been taken, this of course cannot be known. In the absence of this knowledge, and when absolute muscular and other prostration, fainting and other forms of collapse, shallow dyspnoeic breathing, merely trickling or barely perceptible pulse, with no vomiting, no purging, or no alteration of pupils, nor characteristic symptoms of other poisons, poisoning by aconite should be suspected. The action of a lethal dose of aconite is rapid, symptoms coming on within a few minutes. Death may occur in from one half hour to six hours, the average time being a little over three hours.

The treatment of poisoning by aconite should be prompt and quietly administered. The victim must at all hazards be kept in the recumbent position, with the feet slightly elevated. If seen early, tannic acid or strong infusion of common store tea (to occlude the poison) should be administered. External heat should be applied and artificial respiration resorted to as soon as respiratory embarrassment takes place. In the earlier stage emetics may be tried, but will probably fail to act if the stomach has been anaesthetized by the poison. The stomach-pump, or siphon, is to be preferred. Besides, emetics may be inadvisable for fear of the muscular contraction producing heart-failure. Whatever method be followed the stomach contents should be received upon a towel, the patient under no circumstances to be raised from the prostrate position. The chief hope lies in stimulation. Ammonia or alcohol, or Hoffman's anodyne, may be given by mouth, and ether, alcohol, and digitalis hypodermatically. Digitalis is the nearest to a physiological antidote to aconite, but acts very slowly, whereas the action of aconite is rapid. The more diffusible stimulants, therefore, are to be given first, and closely followed by the digitalis. Atropine may stimulate respiration, and caffeine (or hot coffee) sustain the heart. Nitrite of amyl may be used cautiously, allowing but a whiff or two, lest the stimulant action be passed and dangerous depression induced. A full dose of strychnine sulphate or nitrate (1/20 to 1/10 grain) should be given subcutaneously to sustain the heart-action. Of the newer biologic products, possibly adrenalin chloride (1 to 1000) or pituitrin, hypodermatically administered, might aid in preventing circulatory collapse.

Therapy.-External.–As a topical agent, aconite, in tincture or as an ingredient of anodyne liniments, may be applied to relieve pain, allay itching and reduce inflammation. Its use, however, must be guarded as it is readily absorbed. A well-diluted spray gives relief in the early stage of tonsillitis and when quinsy occurs, and it relieves the distress and shortens the duration of faucitis, pharyngitis, and some cases of laryngitis. If used in local inflammations it should be in the earlier stages. Locally applied above the orbits it may give relief in sinusitis; used over the mastoid bone it mitigates the pain of otitis media and modifies external inflammation of the ear. Its obtunding power gives temporary relief in facial and other forms of neuralgia (when hyperaemia is present), the neuralgia preceding zoster, pleurodynia, myalgia, rheumatic gout (rheumatoid arthritis), peridental inflammation, and so-called chronic rheumatism. It also allays the pain and itching of chilblains, and the discomfort of papular eczema, pruritus ani, and other forms of pruritus.

Internal.–Aconite is a most useful internal medicine. The weight of evidence from those who use aconite most frequently shows that it is a safe agent when used in the minute dose and according to specific indications, and is proportionately dangerous as the dose approaches that which produces its physiological action. It is capable of great good in the hands of the cautious and careful therapeutist, and is capable of great harm if carelessly or thoughtlessly employed.

Aconite is the remedy where there is a dilatation from want of tone in the capillary vessels. It moderates the force and frequency of the heart's action, increasing its power, and is, therefore, useful in functional asthenia; it also lessens pain and nervous irritation. Aconite cases are those showing a frequent but free circulation; where there is super-active capillary movement; and in enfeeblement of the circulation, functional in character and not due to structural degeneration or sepsis, and manifested by a frequent small pulse, a hard and wiry pulse, a frequent, open and easily compressed pulse, a rebounding pulse, or an irregular pulse. It lessens determination of blood (hyperaemia), quiets irritation, checks the rapid circulation in the capillaries when it is too active, and increases the circulation when it is sluggish. We account for this by believing that it gives the right innervation to the vascular system. Scudder (Diseases of Children, 42) says of it: "I have been in the habit of saying that aconite is a stimulant to the heart, arteries, and capillaries, because whilst it lessens the frequency, it increases the power of the apparatus engaged in the circulation." It should be stated that our term sedative differs in fact from that accepted by other schools. An agent such as aconite, which in full doses would depress but in minute doses will stimulate the vascular system to normal activity and thereby reduce febrile states by correcting or regulating innervation, is classed in Eclectic therapy as a "special," "vascular," or "arterial sedative."

Aconite is a remedy for irritation of the mucous membranes. It matters little whether it be of the nares preceding an attack of coryza, of the larynx, of the bronchi, or of the gastro-intestinal tube, liable to lead to inflammation of those tracts, aconite may be used to control the morbid process. In simple gastric irritation with or without vomiting, in the irritative forms of diarrhoea—whether simple or of the more complicated forms of enteric inflammation, of cholera infantum, or of dysentery—it is equally important and usually specifically indicated. In the diarrhoea of dentition it often controls the nervous symptoms and the discharges. Of course one must take into consideration the role played by food toxemia. In such cases modification or complete change of food must be resorted to, and frequently a simple purge given to cleanse the gastro-intestinal tract. Then if irritation persists, or there is fever, aconite usually acts promptly. The form of cholera infantum best treated by it is that showing increased bodily heat. If dentition is accompanied by irritation and fever, it may be given alone or with matricaria. In many of the stomach and bowel disorders, particularly gastric irritation with diarrhoea, and gastro-enteritis, it acts well with ipecac, or rhus. For aphthous ulcerations with fever, aconite and phytolacca internally with infusion of coptis locally have not been excelled. In simple dysentery, aconite, ipecac and magnesium sulphate is a most effective combination, seldom failing to control the disease in a few hours.

Aconite allays fever and inflammation, and it's the most commonly used agent for such conditions. When specifically selected it proves useful in glandular fever (with phytolacca) and in acute gastritis and gastric fever, with yellow-coated tongue and diarrhoea. In simple febricula it is diagnostic, if, as Locke has well stated, the patient is not well or markedly improved in twelve hours, he has more than a case of simple fever. In intermittent or malarial fevers it prepares the way for the successful exhibition of antiperiodics. As quinine, the best antagonist of the malarial parasite, acts most kindly when the skin is moist, the tongue soft and clean, and nervous system calm, aconite is signally useful as it establishes those very conditions. In septic fevers, or those depending upon sepsis, the presence of pus, etc., its value is limited, though it may assist other measures. It is especially of value in the fevers of irritation of childhood—such as arise from overloading the stomach, from colds, and from dentition. Most febricula subside quickly, but they do so more quickly and kindly when assisted by the small dose of aconite. So valuable has aconite become in fevers, that by some writers it has been christened the "vegetable lancet;" by Webster, the "pulsatilla of the febrile state;" and by Scudder, the "child's sedative."

In all febrile states in which aconite is indicated there is sudden onset and rapid evolution; moreover, the remedy is seldom needed, nor indeed is it admissible except in the first few days of the invasion. Very rarely is it to be used in the protracted fevers, except at the very outset, and then it must be strongly indicated. It is much better to omit it than to advise its employment in continued fevers of an adynamic type, lest some carelessly or perhaps boldly push it in too large doses or for too long a period to the detriment of the patient. In typhoid or enteric fever there are usually conditions to face which make aconite an ill-advised medicine, except in rare instances in which distinct indications for it may be present. These are so rare, however, as to be pronounced exceptions. The blood disintegration, the toxic impression of the secretions and the nervous system, the defective excretion and the progressive weakening of the heart and circulation, make aconite all but contraindicated in this devitalizing disease. If used at all we question the expediency of employing aconite or any other febrifuge for a prolonged period in typhoid or other adynamic fevers.

In urethral fever, due to catheterization, and in the febrile stage of acute gonorrhoeal urethritis, its action is prompt and effective. It may be used as an auxiliary agent in visceral inflammations of the abdominal and pelvic cavities, when simple in character. In such grave disorders as puerperal fever, because of its highly septic character, it is of questionable utility. The same is true of peritonitis of septic origin.

In the acute infectious diseases (including the infectious fevers already mentioned, but respecting the limitations in typhoid states) aconite is of very great value when used at the onset of the invasion. It is among the best agents in acute tonsillitis and quinsy before pus forms, in the initial stage of la grippe, in acute colds, acute coryza, lobar, and broncho-pneumonia, pleurisy, and allied infections. Here it controls temperature, retards hyperaemia, establishes secretion, prevents effusion when threatened, and gives the nervous system rest. When it alleviates pain it does so chiefly by allaying inflammation. In pleurisy, aconite associated with bryonia is an admirable remedy until effusion takes place, then it no longer is serviceable. To reduce high temperature it is temporarily useful in phthisis when invasion of new portions of the lungs takes place. Aconite may be used in cerebro-spinal meningitis until effusion takes place; after which it should be discarded.

Other disorders of the respiratory tract are benefited by its action as far as irritation, hyperaemia, and inflammation prevail—acute nasal and faucial catarrh, acute pharyngitis, acute bronchitis, acute laryngitis and acute tracheitis. For spasmodic and mucous croup it is the best single remedy, often checking the disease in an hour's time. Aconite was at one time freely used in diphtheria, and is still valued by some, but its use should be carefully guarded for the same reasons stated under typhoid fever. The most it can do is to aid in controlling temperature; and if carelessly employed it may invite paralysis of the heart in a disease itself prone to paralysis through its own toxicity. Aconite should not be omitted in the treatment of erysipelas with high temperature.

Aconite and belladonna are indispensable in the exanthemata, and are the drugs most often indicated. It is to be used when the skin is hot, dry, and burning and the temperature high. By its timely use the eruption is facilitated, the temperature lowered, the secretory organs protected, spasms averted, and damage to the kidneys and the over-wrought nervous system forestalled. It is, therefore, indicated in the initial stages of varicella, measles, scarlatina, and sometimes in variola.

While by no means an antirheumatic, aconite is of marked benefit in acute inflammatory rheumatism, when high fever and great restlessness prevail. Besides it protects the heart by lessening the probability of endocarditis and possible heart failure. The dose, however, must be small lest we induce the very calamity we aim to avoid. Locke regarded it almost a specific in uncomplicated rheumatism; but while it greatly aids in reducing fever, inflammation and pain, it needs the assistance of the more direct antirheumatics and their allies, as sodium salicylate, bryonia and macrotys. More slowly, but less certainly, it sometimes alleviates simple acute neuritis.

Mumps is well treated by aconite, asclepias and phytolacca, while for mastitis aconite, bryonia, and phytolacca are our most effective agents. With careful nursing, emptying of the breasts, and sometimes judicious strapping and supporting of the glands the formation of pus may be averted. Should it form, the bistoury is the only rational medium of relief.

As a remedy for the disorders of the female reproductive organs, aconite is very valuable. It is particularly valuable in recent amenorrhea, due to cold, if the circulation and temperature are increased; and in menorrhagia, with excited circulation and hot, dry skin. Dover's powder or the diaphoretic powder adds to its efficiency. Some rely on it to relieve the nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.

Neuralgic pain is somewhat relieved by aconite, used both locally and internally. The varieties best treated are facial, dental, visceral, and rectal neuralgia, and that preceding herpes zoster. Though most efficient when fever accompanies, it is held to be useful also when the temperature is not exalted. King found aconite a remedy of marked worth in that anomalous condition best described as non-febrile spinal irritation.

Purely functional palpitation of the heart, due to indigestion, has been relieved by small doses of aconite. One of the instances in which large or physiological doses of aconite are permissible is in simple cardiac hypertrophy, but even then veratrum is to be preferred. In very minute doses aconite has been advised by Scudder in the algid stage of Asiatic cholera, and in the cold stage of fevers.

The dried tuberous root of Aconitum napellus, Linné (Nat. Ord. Ranunculaceae). Mountains of Europe and Asia, and northwestern North America. Dose (maximum), 1 grain.

Common Names: Aconite, Monkshood, Wolfsbane.

Principal Constituents.–Aconitine (C34H47O11N) one of the most poisonous of known alkaloids, occurring as permanent colorless or white crystals, without odor. A drop of solution of one part of aconitine in 100,000 of water will produce the characteristic tingling and benumbing sensation of aconite. The alkaloid itself must never be tasted, and the solution only when extremely diluted, and then with the greatest of caution. Aconitine is soluble in alcohol, ether, and benzene; very slightly in water. Other constituents of Aconite are aconine and benzaconine, both alkaloids; the former of little activity; the latter a strong heart depressant.

Commercial Aconitine is a more or less impure mixture of aconite alkaloids.

Preparations.–1. Specific Medicine Aconite. An exceedingly poisonous and representative preparation. Dose, 1/30 to 1/2 drop. (Usual form of administration: Rx Specific Medicine Aconite 1-10 drops: Water 4 fluidounces. Mix. Sig. One teaspoonful every one-half (1/2) to two (2) hours.)

2. Tinctura Aconiti, Tincture of Aconite (10 per cent aconite). Dose, 1 to 8 minims.

Note.—Fleming's Tincture of Aconite is many times stronger than the preceding, with which it should not be confounded. It should have no place in modern therapeutics.

Specific Indications.–The small and frequent pulse, whether corded or compressible, with either elevated or depressed temperature and not due to sepsis, is the most direct indication. Irritation of mucous membranes with vascular excitation and determination of blood; hyperemia; chilly sensations; skin hot and dry, with small, frequent pulse. Early stage of fevers with or without restlessness. When septic processes prevail it is only relatively indicated.

Action.–The effects of aconite, considered from the so-called physiological action, are expressed in local and general irritation followed by tingling, numbness, and peripheral sensory paralysis, primarily reduced force and frequency of the heart action, due to vagal stimulation, and subsequent rapid pulse, due to vagal depression. The heart muscle is also thought to be paralyzed by it. The action upon the vaso-motor system is not well understood, though the lowered arterial pressure is explained by some as due to depression of the vaso-motor center. In small doses aconite quiets hurried breathing, but large doses may cause death through respiratory paralysis. Temperature is lowered by aconite, probably by increase of heat-dissipation and possibly through the action of the thermo-genetic system. This action is most pronounced during fevers. Except of the skin and kidneys, the glands of the body seem to be but little, if at all, affected by aconite. The kidney function is slightly increased, while that of the skin is markedly influenced according to the quantity administered. The motor nervous system is not noticeably affected except when poisonous doses are given, but the sensory nerves, especially at the periphery, are notably impressed by even so-called therapeutic doses. It is quite clear that aconite does not act strongly upon the cerebrum, except that poisonous doses somewhat depress the perceptive faculty. Upon the skin and mucous surfaces it acts first as an irritant, then as an anaesthetic. The mode of elimination of aconite is not yet well determined, but it is thought that it is largely oxidized, thus accounting for the short duration of its action. Indeed, the systemic effects of aconite seldom last over three hours, though the therapeutic result may be permanent. When aconite kills it does so usually by paralyzing the heart, arresting that organ in diastole.

Locally, aconite and its alkaloid, aconitine, act as irritants, producing a tingling, pricking sensation and numbness, followed by peripheral sensory impairment, resulting in anaesthesia of the part. The latter is due to paralysis of the sensory nerve terminals. Usually no redness nor inflammation follows, but in rarely susceptible cases vesicular or pustular eruptions take place, or intense cutaneous itching. Both are extremely irritating to the nasal and ocular membranes, and when inhaled may give rise to a peculiar local sense of icy-coldness.

Administered internally in small doses aconite occasions a tingling or prickling sensation, felt first in the mouth, tongue, and fauces, and quickly extending to the stomach. This is rapidly followed by more or less numbness. Gastric warmth and a general glow of the surface follow non-lethal doses. Slight perspiration may be induced, but sweating to any great degree does not take place except from large doses. Then it is an almost constant symptom. Temperature is reduced, but the more readily during pyrexia, when the pulse is frequent and small, if the dose administered be fractional.

In maximum doses (by some called full therapeutic doses) aconite causes gastric heat. A sense of warmth throughout the system follows, and occasionally the thrilling or tingling sensation will be more generally experienced, with perhaps some numbness. There may be dizziness most marked upon assuming the upright posture, pain in the head, acute body pain, excessive depression, with feeble circulation and diminished respiration. The pulse may fall to 30 or 40 beats per minute and muscular weakness become extreme. Eclectic teaching has long protested against giving aconite in doses sufficient to produce these effects, which some, with extreme boldness, declare to be therapeutic results.

Toxicology.–In poisonous amounts the symptoms given are exaggerated and the effects extremely rapid. Tingling and numbness increase and are felt all over the body, the thrilling and creeping coldness approaching from the extremities to the body. Excessive sweating comes on, rapidly lowering the body temperature, dimness of vision, loss of hearing and touch, and general peripheral paralysis extending from the extremities to the trunk. The victim is conscious of danger, feels cold and is extremely anxious and prostrated. Muscular weakness is pronounced, tremors occur, and rarely convulsions. The power of standing is lost early. The face is extremely pale, the sclerotics pearly, eyes sunken, the countenance one of extreme anxiety, and there is a tendency to fainting. There may be gastric pain and vomiting. If the recumbent position is not maintained, or even if slight exertion be attempted, sudden death may occur from syncope. Unless consciousness be lost through syncope, the intellect remains unimpaired until just before death, showing that aconite probably does not greatly impress the cerebrum.

The one diagnostic symptom of aconite poisoning is the characteristic aconite tingling. If confession (in case of attempted suicide) is not forthcoming or the patient is unable to reveal the fact that poison has been taken, this of course cannot be known. In the absence of this knowledge, and when absolute muscular and other prostration, fainting and other forms of collapse, shallow dyspnoeic breathing, merely trickling or barely perceptible pulse, with no vomiting, no purging, or no alteration of pupils, nor characteristic symptoms of other poisons, poisoning by aconite should be suspected. The action of a lethal dose of aconite is rapid, symptoms coming on within a few minutes. Death may occur in from one half hour to six hours, the average time being a little over three hours.

The treatment of poisoning by aconite should be prompt and quietly administered. The victim must at all hazards be kept in the recumbent position, with the feet slightly elevated. If seen early, tannic acid or strong infusion of common store tea (to occlude the poison) should be administered. External heat should be applied and artificial respiration resorted to as soon as respiratory embarrassment takes place. In the earlier stage emetics may be tried, but will probably fail to act if the stomach has been anaesthetized by the poison. The stomach-pump, or siphon, is to be preferred. Besides, emetics may be inadvisable for fear of the muscular contraction producing heart-failure. Whatever method be followed the stomach contents should be received upon a towel, the patient under no circumstances to be raised from the prostrate position. The chief hope lies in stimulation. Ammonia or alcohol, or Hoffman's anodyne, may be given by mouth, and ether, alcohol, and digitalis hypodermatically. Digitalis is the nearest to a physiological antidote to aconite, but acts very slowly, whereas the action of aconite is rapid. The more diffusible stimulants, therefore, are to be given first, and closely followed by the digitalis. Atropine may stimulate respiration, and caffeine (or hot coffee) sustain the heart. Nitrite of amyl may be used cautiously, allowing but a whiff or two, lest the stimulant action be passed and dangerous depression induced. A full dose of strychnine sulphate or nitrate (1/20 to 1/10 grain) should be given subcutaneously to sustain the heart-action. Of the newer biologic products, possibly adrenalin chloride (1 to 1000) or pituitrin, hypodermatically administered, might aid in preventing circulatory collapse.

Therapy.-External.–As a topical agent, aconite, in tincture or as an ingredient of anodyne liniments, may be applied to relieve pain, allay itching and reduce inflammation. Its use, however, must be guarded as it is readily absorbed. A well-diluted spray gives relief in the early stage of tonsillitis and when quinsy occurs, and it relieves the distress and shortens the duration of faucitis, pharyngitis, and some cases of laryngitis. If used in local inflammations it should be in the earlier stages. Locally applied above the orbits it may give relief in sinusitis; used over the mastoid bone it mitigates the pain of otitis media and modifies external inflammation of the ear. Its obtunding power gives temporary relief in facial and other forms of neuralgia (when hyperaemia is present), the neuralgia preceding zoster, pleurodynia, myalgia, rheumatic gout (rheumatoid arthritis), peridental inflammation, and so-called chronic rheumatism. It also allays the pain and itching of chilblains, and the discomfort of papular eczema, pruritus ani, and other forms of pruritus.

Internal.–Aconite is a most useful internal medicine. The weight of evidence from those who use aconite most frequently shows that it is a safe agent when used in the minute dose and according to specific indications, and is proportionately dangerous as the dose approaches that which produces its physiological action. It is capable of great good in the hands of the cautious and careful therapeutist, and is capable of great harm if carelessly or thoughtlessly employed.

Aconite is the remedy where there is a dilatation from want of tone in the capillary vessels. It moderates the force and frequency of the heart's action, increasing its power, and is, therefore, useful in functional asthenia; it also lessens pain and nervous irritation. Aconite cases are those showing a frequent but free circulation; where there is super-active capillary movement; and in enfeeblement of the circulation, functional in character and not due to structural degeneration or sepsis, and manifested by a frequent small pulse, a hard and wiry pulse, a frequent, open and easily compressed pulse, a rebounding pulse, or an irregular pulse. It lessens determination of blood (hyperaemia), quiets irritation, checks the rapid circulation in the capillaries when it is too active, and increases the circulation when it is sluggish. We account for this by believing that it gives the right innervation to the vascular system. Scudder (Diseases of Children, 42) says of it: "I have been in the habit of saying that aconite is a stimulant to the heart, arteries, and capillaries, because whilst it lessens the frequency, it increases the power of the apparatus engaged in the circulation." It should be stated that our term sedative differs in fact from that accepted by other schools. An agent such as aconite, which in full doses would depress but in minute doses will stimulate the vascular system to normal activity and thereby reduce febrile states by correcting or regulating innervation, is classed in Eclectic therapy as a "special," "vascular," or "arterial sedative."