Boswellia sacra

Frankincense Summary

- All frankincense-producing species of Boswellia are in grave ecological peril.

- All species except B. serrata grow in areas heavily affected by war and conflict; buying frankincense does not help this situation.

- Most companies simply do not reveal the source of their frankincense, raising concerns about "blood frankincense" (i.e. it is being purchased out of conflict areas under highly dubious conditions, both politically and ecologically). Do not buy or recommend frankincense unless it is from cultivated sources or confirmable, sustainable, fair trade sources (which are largely not available).

- Though there are many positive clinical trials on frankincense, it is simply not sustainable (instead, it is actively declining).

- We have extremely widespread, sustainable sources of resins that are good substitutes for frankincense widely available throughout North America and Europe, notably most members of the Pinaceae family.

Frankincense: Powerful but Endangered

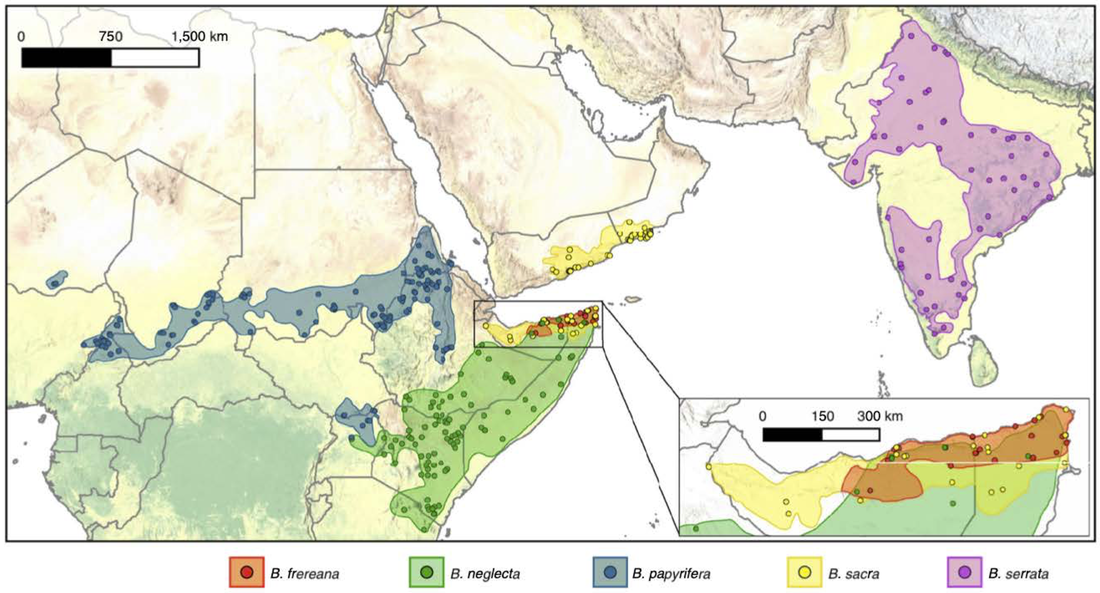

All the major medicinal species of Boswellia are threatened or endangered (see the map below for the native range of these species). They suffer numerous problems and the most important sources of the resinous medicine known as frankincense are in major decline. A brief summary fo the problems facing frankincense-producing species is provided along with alternatives to them. The most threatened species were formerly major sources of frankincense resin, B. sacra and B. serrata. However, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), B. sacra is near threatened (but this was last assessed in 1998), and B. serrata is vulnerable in India (though it appears to be more wide spread in some areas per Brendler, et al. 2018) and critically endangered/possibly extinct in Sri Lanka. Other species have not been assessed by IUCN.

Currently the vast majority of frankincense comes from B. papyrifera, which as shown grows in a belt stretching from the Horn of Africa in Eritrea and Ethiopia cross Sudan and into the Central African Republic and Cameroon, with small disjunct populations in Uganda and Niger (Bongers, et al. 2019). B. sacra, principally found in northern Somalia and Yemen, used to be a major source of frankincense but it has become so depleted that it is now not contributing to world supply practically at all. This is a warning and a lesson: uncontrolled tapping of this resource led to its collapse.

Data from tree growth ring sampling confirms virtually no tree regeneration for B. papyrifera since the 1950s for many populations, others since the 1960s or 1980s in Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan (Bongers, et al. 2019). Thus this problem has been going on with virtually no knowledge in the herbal industry or among consumers in the developed world for decades. As scientific data mount and become increasingly well known, claiming ignorance or lack of data are no longer (if they ever were!) reasonable excuses for the ongoing unsustainable sourcing of frankincense.

Complicating this situation is the economic importance of frankincense (and myrrh). There is no other significant industry or work available in much of northern Somalia (which due to a long-lasting civil war really is a non-state), Yemen (embroiled in a horrific civil/regional war as of 2022), and north central Ethiopia (Laggan 2011, now also in the midst of a massive civil war in 2022). These are among the poorest places in the world. War, poverty, drought, population growth, and other factors push people to practice unsustainable resin tapping and to encroach on the habitat of the frankincense trees, and have led to dramatic reduction in the number of mature trees, and a near total elimination of juvenile trees (Bongers, et al. 2019).

In Ethiopia there is clear evidence that local people receive little profit from harvesting B. papyrifera compared to economic activities that damage its habitat, such as cattle grazing and clearing the land to grow sesame and other crops (Lemenih, et al. 2007). So just buying whatever random product off the shelves with no idea of the source of the frankincense is very unlikely to improve the lives of poor people. Only ethical sourcing that cuts out middle men (and they are almost entirely men) and deals directly with incense tappers, or using cultivated sources, is likely to help, and almost none of this is happening. Certainly any supplier that doesn't disclose their source is highly unlikely to be following fair trade, sustainable sourcing practices.

"Boswellia populations are threatened by over-exploitation and ecosystem degradation, jeopardizing future resin production. Here, we reveal evidence of population collapse of B. papyrifera--now the main source of frankincense--throughout its geographic range." –Bongers 2019 (emphasis added)

Numerous factors have been documented to play into the rapid and widespread decline of all sources of frankincense, including (Bongers, et al. 2019; Brendler, et al. 2018; Lemineh, et al. 2014 and 2007; Ogbazghi, et al. 2006):

Additional photos of frankincense and its harvest and uses are available here.

- Habit loss due to human encroachment

- Unsustainably overharvesting, including cutting trees down, "careless tapping" and "full debarking" (all lethal to the trees)

- Overgrazing (particularly of seedlings) by cattle, goats and other livestock (not wild animals)

- Fire, drought, and other effects of climate change

- Firewood collecting (B. neglecta in particular)

- Competition and other damage from invasive species (insects and plants), particularly the wood-boring beetle Idactus spinipennis (for B. papyrifera, Negussie, et al. 2018)

- Lack of knowledge of how to sustainably harvest it (in some areas)

Additional photos of frankincense and its harvest and uses are available here.

Please click here to learn more about the vital role Boswellia spp play in their native habitats. Saving these trees is not only about preserving them for human use, for but for preserving the entire ecosystems in which they live.

Solutions

The most important and immediate thing most people can do is to stop buying frankincense from companies that do not reveal their sources, or that are clearly buying from unsustainable or conflict-tainted sources.

Second, you can buy materials from the tiny handful of companies that offer fair trade and sustainable sourcing of frankincense (Laggan 2011). These generally are more expensive than unsustainable frankincense sources, but much more of the money is flowing to the poor people of Africa who really need it.

Third, you can use or recommend substitutes. Populus spp (poplar), Pinus spp (pine), Abies spp (fir), Tsuga spp (hemlock), Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas fir), and Picea spp (spruce) resins are all superabundant trees that provide resins sustainably with much similarity to frankincense based on traditional use. Additional options are listed below.

Alternatives/substitutes by indications for frankincense with clinical trial support:

Asthma:

Crocus sativa (saffron) (Zilaee, et al. 2019)

Curcuma longa (turmeric) (Manarin, et al. 2019)

Hedera helix (ivy), meta-analysis (Hofmann, et al. 2003)

Nigella sativa (black cumin) (He, et al. 2020)

Inflammatory bowel disease:

Artemisia absinthium (wormwood) (Krebs, et al. 2010; Omer, et al. 2007)

Cannabis sativa (cannabis), review of studies (Carvalho, et al. 2020)

Curcuma longa (turmeric) curcumin, meta-analysis (Coelho, et al. 2020)

Pistachia lentiscus (mastic gum) (Kaliora, et al. 2007)

Plantago ovata (psyllium) seed (Fernández-Bañares, et al. 1999)

Osteoarthritis:

Curcuma longa (turmeric) crude extracts and curcumin, meta-analysis (Perkins, et al. 2017)

Elaeagnus angustifolia (Russian olive) (Karimifar, et al. 2017)

Mineral water bath (Hanzel, et al. 2019)

Pine bark extract (Cisár, et al. 2008)

Please support the HALO Trust which is working to clear minefields in Somalia to help local people restart local, sustainable frankincense harvesting.

Second, you can buy materials from the tiny handful of companies that offer fair trade and sustainable sourcing of frankincense (Laggan 2011). These generally are more expensive than unsustainable frankincense sources, but much more of the money is flowing to the poor people of Africa who really need it.

Third, you can use or recommend substitutes. Populus spp (poplar), Pinus spp (pine), Abies spp (fir), Tsuga spp (hemlock), Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas fir), and Picea spp (spruce) resins are all superabundant trees that provide resins sustainably with much similarity to frankincense based on traditional use. Additional options are listed below.

Alternatives/substitutes by indications for frankincense with clinical trial support:

Asthma:

Crocus sativa (saffron) (Zilaee, et al. 2019)

Curcuma longa (turmeric) (Manarin, et al. 2019)

Hedera helix (ivy), meta-analysis (Hofmann, et al. 2003)

Nigella sativa (black cumin) (He, et al. 2020)

Inflammatory bowel disease:

Artemisia absinthium (wormwood) (Krebs, et al. 2010; Omer, et al. 2007)

Cannabis sativa (cannabis), review of studies (Carvalho, et al. 2020)

Curcuma longa (turmeric) curcumin, meta-analysis (Coelho, et al. 2020)

Pistachia lentiscus (mastic gum) (Kaliora, et al. 2007)

Plantago ovata (psyllium) seed (Fernández-Bañares, et al. 1999)

Osteoarthritis:

Curcuma longa (turmeric) crude extracts and curcumin, meta-analysis (Perkins, et al. 2017)

Elaeagnus angustifolia (Russian olive) (Karimifar, et al. 2017)

Mineral water bath (Hanzel, et al. 2019)

Pine bark extract (Cisár, et al. 2008)

Please support the HALO Trust which is working to clear minefields in Somalia to help local people restart local, sustainable frankincense harvesting.

Sustainable, Fair Trade Sources

One confirmed source of cultivated B. sacra and some other frankincense species, as well as myrrh, is the Balm of Gilead Farm in Israel.

It also appears that Böswellness works directly with frankincense and myrrh harvesters in Somaliland in a sustainable and fair-trade method.

Dr. Yarnell has no connection with or financial interest in any of these companies. They are linked here solely in the interest of promoting and sustaining frankincense and the people who live with these amazing trees.

It also appears that Böswellness works directly with frankincense and myrrh harvesters in Somaliland in a sustainable and fair-trade method.

Dr. Yarnell has no connection with or financial interest in any of these companies. They are linked here solely in the interest of promoting and sustaining frankincense and the people who live with these amazing trees.

References

Bongers F, Groenendijk P, Bekele T, et al. (2019) "Frankincense in peril" Nature Sustainability 2:602–10.

Brendler T, Brinckmann JA, Schippmann U (2018) "Sustainable supply, a foundation for natural product development: The case of Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata Roxb ex Colebr)" J Ethnopharmacol 225:279–86.

Carvalho ACA, Souza GA, Marqui SV, et al. (2020) "Cannabis and canabidinoids on the inflammatory bowel diseases: Going beyond misuse" Int J Mol Sci 21(8):2940.

Cisár P, Jány R, Waczulíková I, et al. (2008) "Effect of pine bark extract (Pycnogenol) on symptoms of knee osteoarthritis" Phytother Res 22(8):1087–92.

Coelho MR, Romi MD, Ferreira DMTP, et al. (2020) "The use of curcumin as a complementary therapy in ulcerative colitis: A systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials" Nutrients 12(8):2296.

Fernández-Bañares F, Hinojosa J, Sánchez-Lombraña JL, et al. (1999) "Randomized clinical trial of Plantago ovata seeds (dietary fiber) as compared with mesalamine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis. Spanish Group for the Study of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU)" Am J Gastroenterol 94(2):427–33.

Groenendijk P, Eshete A, Sterck FJ, et al. (2012) "Limitations to sustainable frankincense production: Blocked regeneration, high adult mortality and declining populations" J Appl Ecol 49:164–73.

Hanzel A, Berényi K, Horváth K, et al. (2019) "Evidence for the therapeutic effect of the organic content in Szigetvár thermal water on osteoarthritis: A double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial" Int J Biometeorol 63(4):449–58.

He T, Xu X (2020) "The influence of Nigella sativa for asthma control: A meta-analysis" Am J Emerg Med 38(3):589–93.

Hofmann D, Hecker M, Völp A (2003) "Efficacy of dry extract of ivy leaves in children with bronchial asthma---a review of randomized controlled trials" Phytomedicine 10(2–3):213–20.

Kaliora AC, Stathopoulou MG, Triantafillidis JK, et al. (2007) "Chios mastic treatment of patients with active Crohn's disease" World J Gastroenterol 13(5):748–53.

Karimifar M, Soltani R, Hajhashemi V, Sarrafchi S (2017) "Evaluation of the effect of Elaeagnus angustifolia alone and combined with Boswellia thurifera compared with ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial" Clin Rheumatol 36(8):1849–53.

Krebs S, Omer TN, Omer B (2010) "Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) suppresses tumour necrosis factor alpha and accelerates healing in patients with Crohn's disease---A controlled clinical trial" Phytomedicine 17(5):305–9.

Laggan S (2011) "Frankincense and myrrh: An ethical nightmare?" Ecologist: The Journal for the Post-Industrial Age (article link here)

Lemenih M, Arts B, Wiersum KF, Bongers F (2014) "Modelling the future of Boswellia papyrifera population and its frankincense production" J Arid Environ 105:33–40.

Lemenih M, Feleke S, Tadesse W (2007) “Constraints to smallholders production of frankincense in Metema District, North-western Ethiopia” J Arid Environ 71:393–403.

Manarin G, Anderson D, Silva JME, et al. (2019) "Curcuma longa L ameliorates asthma control in children and adolescents: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial" J Ethnopharmacol 238:111882.

Negussie A, Gebrehiwot K, Yohannes M, et al. (2018) "An exploratory survey of long horn beetle damage on the dryland flagship T tree species Boswellia papyrifera (Del) Hochst" J Arid Environ 152:6–11.

Ogbazghi W, Rijkers T, Wessel M, Bongers F (2006) "Distribution of the frankincese tree Boswellia papyrifera in Eritrea: The role of environment and land use" J Biogeogr 33:524–35.

Omer B, Krebs S, Omer H, Noor TO (2007) "Steroid-sparing effect of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) in Crohn's disease: A double-blind placebo-controlled study" Phytomedicine 14(2–3):87–95.

Perkins K, Sahy W, Beckett RD (2017) "Efficacy of Curcuma for treatment of osteoarthritis" J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 22(1):156-165.

Zilaee M, Hosseini SA, Jafarirad S, et al. (2019) "An evaluation of the effects of saffron supplementation on the asthma clinical symptoms and asthma severity in patients with mild and moderate persistent allergic asthma: A double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial" Respir Res 20(1):39.

Brendler T, Brinckmann JA, Schippmann U (2018) "Sustainable supply, a foundation for natural product development: The case of Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata Roxb ex Colebr)" J Ethnopharmacol 225:279–86.

Carvalho ACA, Souza GA, Marqui SV, et al. (2020) "Cannabis and canabidinoids on the inflammatory bowel diseases: Going beyond misuse" Int J Mol Sci 21(8):2940.

Cisár P, Jány R, Waczulíková I, et al. (2008) "Effect of pine bark extract (Pycnogenol) on symptoms of knee osteoarthritis" Phytother Res 22(8):1087–92.

Coelho MR, Romi MD, Ferreira DMTP, et al. (2020) "The use of curcumin as a complementary therapy in ulcerative colitis: A systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials" Nutrients 12(8):2296.

Fernández-Bañares F, Hinojosa J, Sánchez-Lombraña JL, et al. (1999) "Randomized clinical trial of Plantago ovata seeds (dietary fiber) as compared with mesalamine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis. Spanish Group for the Study of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU)" Am J Gastroenterol 94(2):427–33.

Groenendijk P, Eshete A, Sterck FJ, et al. (2012) "Limitations to sustainable frankincense production: Blocked regeneration, high adult mortality and declining populations" J Appl Ecol 49:164–73.

Hanzel A, Berényi K, Horváth K, et al. (2019) "Evidence for the therapeutic effect of the organic content in Szigetvár thermal water on osteoarthritis: A double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial" Int J Biometeorol 63(4):449–58.

He T, Xu X (2020) "The influence of Nigella sativa for asthma control: A meta-analysis" Am J Emerg Med 38(3):589–93.

Hofmann D, Hecker M, Völp A (2003) "Efficacy of dry extract of ivy leaves in children with bronchial asthma---a review of randomized controlled trials" Phytomedicine 10(2–3):213–20.

Kaliora AC, Stathopoulou MG, Triantafillidis JK, et al. (2007) "Chios mastic treatment of patients with active Crohn's disease" World J Gastroenterol 13(5):748–53.

Karimifar M, Soltani R, Hajhashemi V, Sarrafchi S (2017) "Evaluation of the effect of Elaeagnus angustifolia alone and combined with Boswellia thurifera compared with ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial" Clin Rheumatol 36(8):1849–53.

Krebs S, Omer TN, Omer B (2010) "Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) suppresses tumour necrosis factor alpha and accelerates healing in patients with Crohn's disease---A controlled clinical trial" Phytomedicine 17(5):305–9.

Laggan S (2011) "Frankincense and myrrh: An ethical nightmare?" Ecologist: The Journal for the Post-Industrial Age (article link here)

Lemenih M, Arts B, Wiersum KF, Bongers F (2014) "Modelling the future of Boswellia papyrifera population and its frankincense production" J Arid Environ 105:33–40.

Lemenih M, Feleke S, Tadesse W (2007) “Constraints to smallholders production of frankincense in Metema District, North-western Ethiopia” J Arid Environ 71:393–403.

Manarin G, Anderson D, Silva JME, et al. (2019) "Curcuma longa L ameliorates asthma control in children and adolescents: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial" J Ethnopharmacol 238:111882.

Negussie A, Gebrehiwot K, Yohannes M, et al. (2018) "An exploratory survey of long horn beetle damage on the dryland flagship T tree species Boswellia papyrifera (Del) Hochst" J Arid Environ 152:6–11.

Ogbazghi W, Rijkers T, Wessel M, Bongers F (2006) "Distribution of the frankincese tree Boswellia papyrifera in Eritrea: The role of environment and land use" J Biogeogr 33:524–35.

Omer B, Krebs S, Omer H, Noor TO (2007) "Steroid-sparing effect of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) in Crohn's disease: A double-blind placebo-controlled study" Phytomedicine 14(2–3):87–95.

Perkins K, Sahy W, Beckett RD (2017) "Efficacy of Curcuma for treatment of osteoarthritis" J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 22(1):156-165.

Zilaee M, Hosseini SA, Jafarirad S, et al. (2019) "An evaluation of the effects of saffron supplementation on the asthma clinical symptoms and asthma severity in patients with mild and moderate persistent allergic asthma: A double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial" Respir Res 20(1):39.