by Eric Yarnell, ND, RH(AHG)

Last updated 28 Feb 2022

This monograph is protected by copyright and is intended only for use by health care professionals and students. You may link to this page if you are sharing it with others in health care, but may not otherwise copy, alter, or share this material in any way. By accessing this material you agree to hold the author harmless for any use of this information.Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site. Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site.

Table of Contents

Clinical Highlights

Pipsissewa is a urinary tract tonic and antimicrobial.

Pipsissewa is extremely safe.

Pipsissewa is generally mild, but can be effective even against multidrug-resistant uropathogens.

Pipsissewa is extremely safe.

Pipsissewa is generally mild, but can be effective even against multidrug-resistant uropathogens.

Clinical Fundamentals

Part Used: Fresh flowering tops and some root (though avoiding harvesting the root is more sustainable). The plant withstands low-heat drying moderately well.

Taste: astringent

Major Actions:

A 70% ethanol tincture of pipsissewa inhibited Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes in vitro (Sheth, et al. 1967). An ethanol extract of pipsissewa killed E. coli, S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and C. albicans in vitro in another assay, but only at high concentrations (Vandal, et al. 2015).

Major Organ System Affinities

Major Indications:

Pipsissewa is potentially helpful in any recurrent or chronic urinary tract disorder including incontinence, neurogenic bladder, interstitial cystitis, radiation cystitis, etc. to strengthen bladder function and prevent urinary tract infections. There is, however, a total dearth of clinical trials confirming these traditional indications (and extrapolations from them).

Major Constituents:

Various quinone and phenolic glycosides appear to be important components of this herb, including arbutoside (also called arbutin), isohomoarbutin (Walewska and Thieme 1969), chimaphilin, and related compounds. The arbutoside content of pipsissewa leaf is reported to be 75,000 ppm, compared to 270,000 ppm in Arbutus unedo (strawberry tree), 120,000 ppm in Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (uva-ursi), and 90,000 ppm in Vaccinium vitis-idaea (lingonberry) (USDA 2008).

Adverse Effects: Digestive upset from tannins is the only common problem. Taking pipsissewa with food generally avoids this complication.

Though pure chimaphilin is a moderately-strong contact sensitizer, topical reactions to whole pipsissewa, or crude extracts of it, are extremely rare (Hausen and Schiedermair 1988).

The fresh leaves, when bruised and applied to the skin, may produce redness, vesication, and desquammation (Pereira 1842, Piffard 1881, White 1887, Felter & Lloyd 1898). Schwartz et al. (1947) included this species in a list of irritant plants without making reference to the source of their information.

Contraindications: None known

Drug Interactions: Do to the theoretical risk of the tannins in pipsissewa interfering with absorption of many drugs, it may be best to take them separated in time. Certainly drugs that should be taken away from food must be taken away from pipsissewa.

Taste: astringent

Major Actions:

- Urinary tract tonic (Griffith 1847)

- Astringent, particularly to urinary tract

- Urinary antiseptic (Vandal, et al. 2015; Sheth, et al. 1967; Bishop 1951)

A 70% ethanol tincture of pipsissewa inhibited Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes in vitro (Sheth, et al. 1967). An ethanol extract of pipsissewa killed E. coli, S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and C. albicans in vitro in another assay, but only at high concentrations (Vandal, et al. 2015).

Major Organ System Affinities

- Urinary Tract

Major Indications:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs): acute, recurrent, chronic, and multidrug resistant

- Recurrent and chronic urinary tract conditions

- Gastrointestinal infections

Pipsissewa is potentially helpful in any recurrent or chronic urinary tract disorder including incontinence, neurogenic bladder, interstitial cystitis, radiation cystitis, etc. to strengthen bladder function and prevent urinary tract infections. There is, however, a total dearth of clinical trials confirming these traditional indications (and extrapolations from them).

Major Constituents:

- Phenolic glycosides (Trubachev and Batiuk 1969)

- Tannins

Various quinone and phenolic glycosides appear to be important components of this herb, including arbutoside (also called arbutin), isohomoarbutin (Walewska and Thieme 1969), chimaphilin, and related compounds. The arbutoside content of pipsissewa leaf is reported to be 75,000 ppm, compared to 270,000 ppm in Arbutus unedo (strawberry tree), 120,000 ppm in Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (uva-ursi), and 90,000 ppm in Vaccinium vitis-idaea (lingonberry) (USDA 2008).

Adverse Effects: Digestive upset from tannins is the only common problem. Taking pipsissewa with food generally avoids this complication.

Though pure chimaphilin is a moderately-strong contact sensitizer, topical reactions to whole pipsissewa, or crude extracts of it, are extremely rare (Hausen and Schiedermair 1988).

The fresh leaves, when bruised and applied to the skin, may produce redness, vesication, and desquammation (Pereira 1842, Piffard 1881, White 1887, Felter & Lloyd 1898). Schwartz et al. (1947) included this species in a list of irritant plants without making reference to the source of their information.

Contraindications: None known

Drug Interactions: Do to the theoretical risk of the tannins in pipsissewa interfering with absorption of many drugs, it may be best to take them separated in time. Certainly drugs that should be taken away from food must be taken away from pipsissewa.

Pharmacy Essentials

Tincture: 1:2–1:3 w:v ratio, 30% ethanol

Dose:

Acute, adult: 2–5 ml up to q2h for 2–3 days, adjusted for body size and sensitivities

Chronic, adult: 2–5 ml tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Glycerite: 1:3 w:v ratio, 75%+ vegetable glycerin

Infusion: 5 g (1 heaping tsp) of leaf infused in 250 ml of recently-boiled water for 15–30 min, the result of which makes one cup (not 8 oz, but one dose). The amount of water used can be adjusted to patient taste in subsequent cups.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup up to q2 hours for 2–3 days

Chronic, adult: 1 cup tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Capsules:

Dose:

Acute, adult: 1–2 g per dose, otherwise dosed as with acute tincture

Chronic, adult: 1–2 g tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Dose:

Acute, adult: 2–5 ml up to q2h for 2–3 days, adjusted for body size and sensitivities

Chronic, adult: 2–5 ml tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Glycerite: 1:3 w:v ratio, 75%+ vegetable glycerin

Infusion: 5 g (1 heaping tsp) of leaf infused in 250 ml of recently-boiled water for 15–30 min, the result of which makes one cup (not 8 oz, but one dose). The amount of water used can be adjusted to patient taste in subsequent cups.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup up to q2 hours for 2–3 days

Chronic, adult: 1 cup tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Capsules:

Dose:

Acute, adult: 1–2 g per dose, otherwise dosed as with acute tincture

Chronic, adult: 1–2 g tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Other Names

Latin synonyms:

Current correct Latin binomial: Chimaphila umbellata (L) Nutt

Chimaphila cymosa J Presl & C Presl

Pseva umbellata Kuntze

Pyrola umbellata L

Chimaphila < Greek χειμα (cheima) "winter" and φιλος (philos) "lover."

English Common Names: pipsissewa, prince's pine, noble prince's pine, ground holly, wintergreen, umbellate wintergreen, bitter wintergreen, butter winter, fragrant wintergreen, love in winter, king's cure.

Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe, Chippewa) Common Name: ga’gige’bug ("everlasting leaf")

Czech Common Names: zimozelen okoličnatý, jednokvítek okolíkatý

Dakeł ᑕᗸᒡ (Southern Carrier, Ulkatcho dialect) Common Names: dəәnihcho t’an (possibly "big kinnikinnick"), dihiyii

Danish Common Names: skærm-vintergrøn, skærmblomstret vintergrøn

Dutch Common Names: kaal stofzaad, wintergroen soort

Esperanto Common Names: ĥimafilo, pirolo ombrela

Estonian Common Name: harilik talvik

Finnish Common Names: sarjakukkainen varputalvikki, sarjatalvikki, kangassarjatalvikki

French Common Names: pyrole en ombrelle, poirier en ombelle, herbe à pisser

German Common Names: Winterlieb ("winter-loving"), Nabel-Gichtkraut, Harn-Gichtkraut, Waldmangold, Dolden-Winterlieb, doldiges Winterlieb, doldiges Wintergrün

Gitxsanimaax (Gitxsan) Common Names: hisgant’imiʔyt, hissqan t’imiiʔit

Halq̓eméylem (Upriver Halkomelem dialect) Common Name: chəә́ chəәləәx

Hul̓q̓umín̓um̓ (Quw’utsun’Island Halkomelem dialect) Common Name: qwʔqn-áłp

Hungarian Common Names: ernyőskörtike, közönséges ernyőskörtike

Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit (Sahaptin) Common Name: tamuxit-pamá ("for tuberculosis")

Innu-aimun (Montagnais) Common Name: ci'ci'pma'n ("duck berry")

Japanese Common Name: オオウメガサソウ, 大梅笠草 (ooumegasasou)

Karuk Common Name: hunyeip rukwtixa ("that which grows in the oaks")

Katapa (Catawba) Common Names: i·pi· sara’k, i·pi· sura ́·k ("fire grass")

Ktunaxa (Kootenai) Common Names: ʔa·kpi¢̕is ǂawu, qaqnałiłxaqa (spelling unsure, "dries your eyes"), kanó’os tsakáwok ("red kinnikinnick")

Latvian Common Names: čemuru himafila, čemuru palēki, čemuru palēks, mātes zāle, čemurainā ziemciete

Lithuanian Common Names: baravinkos, barvinkos, kūlių bruknės, drugžolė, kūlpipiriai, skėtinė marenikė,morenka, pamarenės, stanauninkas, trūkžolynis

Mandarin Chinese Common Name: 伞形喜冬草 sǎn xíng xǐ dōng cǎo ("umbrella-shaped herb that loves the winter")

Nēhiyawēwin (Cree) Common Names: pipsissewa ("breaks stones into small pieces"), amiskwathowipak

Nlaka'pamuctsin (Thompson) Common Names: snúkw’eʔs e ʔikéłp ("friend/relative of kinnikinnick"), iwawaqín ("medicine for childbirth")

Norwegian Common Names: bittergrønn ("bitter green"), skjermvintergrønn

n̓səl̓xcin (Okanagan) Common Names: kew’esw’esxn’íkaʔst ("ong little leaves"), tkaʔkaʔłl’íkst ("a bunch of three-leafed ones"

Oma͞eqnomenew (Menominee) Common Name: käkîkä'pûk ("evergreen"). Note Arctostaphylos uva-ursi is called käkîkä'pûtkosa ("little evergreen")

Polish Common Name: pomocnik baldaszkowy

Romanian Common Name: verdeata iernii

Russian Common Names: Грушанка зонтичная (Grušanka zontičnaâ), Зимолюбка зонтичная (Zimolûbka zontičnaâ)

Séliš (Spokane) Common Names: kew’esw’esxn’íka, schxəәlxəәlpú(s) ("eye brightener")

Slovak Common Name: zimoľub okolíkatý

Slovene Common Name: zelenček kobulasti

Spanish Common Names: chimaphila, quimafila

sƛ̓áƛ̓y̌əmx (Pemberton) Common Name: k’əәts-k’əә́ k’(əәk’)tsaʔqw

Swedish Common Name: ryl

Turkish Common Name: kekliküzümü

Ukrainian Common Name: Зимолюбка зонтична (Zymoli͡ubka zontychna)

Wazhazhe ie (Osage) Common Name: ne-was-char-la-go-ne ("good for coughs/colds")

Wôbanakiôdwawôgan (Eastern Abenaki) Common Names: kpipskwáhsawe ("flower of the wood"), tcilkase'sowe'i'gil ("things for scorching [applied to blisters]")

Current correct Latin binomial: Chimaphila umbellata (L) Nutt

Chimaphila cymosa J Presl & C Presl

Pseva umbellata Kuntze

Pyrola umbellata L

Chimaphila < Greek χειμα (cheima) "winter" and φιλος (philos) "lover."

English Common Names: pipsissewa, prince's pine, noble prince's pine, ground holly, wintergreen, umbellate wintergreen, bitter wintergreen, butter winter, fragrant wintergreen, love in winter, king's cure.

Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe, Chippewa) Common Name: ga’gige’bug ("everlasting leaf")

Czech Common Names: zimozelen okoličnatý, jednokvítek okolíkatý

Dakeł ᑕᗸᒡ (Southern Carrier, Ulkatcho dialect) Common Names: dəәnihcho t’an (possibly "big kinnikinnick"), dihiyii

Danish Common Names: skærm-vintergrøn, skærmblomstret vintergrøn

Dutch Common Names: kaal stofzaad, wintergroen soort

Esperanto Common Names: ĥimafilo, pirolo ombrela

Estonian Common Name: harilik talvik

Finnish Common Names: sarjakukkainen varputalvikki, sarjatalvikki, kangassarjatalvikki

French Common Names: pyrole en ombrelle, poirier en ombelle, herbe à pisser

German Common Names: Winterlieb ("winter-loving"), Nabel-Gichtkraut, Harn-Gichtkraut, Waldmangold, Dolden-Winterlieb, doldiges Winterlieb, doldiges Wintergrün

Gitxsanimaax (Gitxsan) Common Names: hisgant’imiʔyt, hissqan t’imiiʔit

Halq̓eméylem (Upriver Halkomelem dialect) Common Name: chəә́ chəәləәx

Hul̓q̓umín̓um̓ (Quw’utsun’Island Halkomelem dialect) Common Name: qwʔqn-áłp

Hungarian Common Names: ernyőskörtike, közönséges ernyőskörtike

Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit (Sahaptin) Common Name: tamuxit-pamá ("for tuberculosis")

Innu-aimun (Montagnais) Common Name: ci'ci'pma'n ("duck berry")

Japanese Common Name: オオウメガサソウ, 大梅笠草 (ooumegasasou)

Karuk Common Name: hunyeip rukwtixa ("that which grows in the oaks")

Katapa (Catawba) Common Names: i·pi· sara’k, i·pi· sura ́·k ("fire grass")

Ktunaxa (Kootenai) Common Names: ʔa·kpi¢̕is ǂawu, qaqnałiłxaqa (spelling unsure, "dries your eyes"), kanó’os tsakáwok ("red kinnikinnick")

Latvian Common Names: čemuru himafila, čemuru palēki, čemuru palēks, mātes zāle, čemurainā ziemciete

Lithuanian Common Names: baravinkos, barvinkos, kūlių bruknės, drugžolė, kūlpipiriai, skėtinė marenikė,morenka, pamarenės, stanauninkas, trūkžolynis

Mandarin Chinese Common Name: 伞形喜冬草 sǎn xíng xǐ dōng cǎo ("umbrella-shaped herb that loves the winter")

Nēhiyawēwin (Cree) Common Names: pipsissewa ("breaks stones into small pieces"), amiskwathowipak

Nlaka'pamuctsin (Thompson) Common Names: snúkw’eʔs e ʔikéłp ("friend/relative of kinnikinnick"), iwawaqín ("medicine for childbirth")

Norwegian Common Names: bittergrønn ("bitter green"), skjermvintergrønn

n̓səl̓xcin (Okanagan) Common Names: kew’esw’esxn’íkaʔst ("ong little leaves"), tkaʔkaʔłl’íkst ("a bunch of three-leafed ones"

Oma͞eqnomenew (Menominee) Common Name: käkîkä'pûk ("evergreen"). Note Arctostaphylos uva-ursi is called käkîkä'pûtkosa ("little evergreen")

Polish Common Name: pomocnik baldaszkowy

Romanian Common Name: verdeata iernii

Russian Common Names: Грушанка зонтичная (Grušanka zontičnaâ), Зимолюбка зонтичная (Zimolûbka zontičnaâ)

Séliš (Spokane) Common Names: kew’esw’esxn’íka, schxəәlxəәlpú(s) ("eye brightener")

Slovak Common Name: zimoľub okolíkatý

Slovene Common Name: zelenček kobulasti

Spanish Common Names: chimaphila, quimafila

sƛ̓áƛ̓y̌əmx (Pemberton) Common Name: k’əәts-k’əә́ k’(əәk’)tsaʔqw

Swedish Common Name: ryl

Turkish Common Name: kekliküzümü

Ukrainian Common Name: Зимолюбка зонтична (Zymoli͡ubka zontychna)

Wazhazhe ie (Osage) Common Name: ne-was-char-la-go-ne ("good for coughs/colds")

Wôbanakiôdwawôgan (Eastern Abenaki) Common Names: kpipskwáhsawe ("flower of the wood"), tcilkase'sowe'i'gil ("things for scorching [applied to blisters]")

Subspecies of Chimaphila umbellata

| Subspecies | Native range | |

| C. umbellata acuta (Rydb.) Hultén | southwestern North America | |

| C. umbellata ssp cisatlantica Húlten = C. corymbosa Pursh | northeastern North America | |

| C. umbellata ssp domingenesis (SF Blake) Dorr | Hispaniola | |

| C. umbellata ssp mexicana (DC) Húlten | Mexico | |

| C. umbellata ssp umbellata | Eurasia | |

The morphological differences between the subspecies are generally obscure and all are quite variable in form. The main exception is subspecies domingensis, given its greater geographic isolation, which has glabrous peduncles, pedicels, and filaments, smaller leaves, and rugulate pollen (Takahashi 1986).

Interchangeability of Species

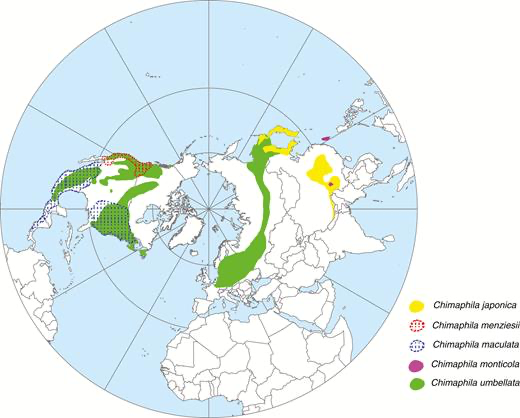

All species in the genus are likely medicinal, but none are used anywhere close to the frequency of C. umbellata overall. Found in a similar distribution, but also extending more throughout the southeastern USA, is C. maculata, which is called ratsvein, spotted wintergreen, striped wintergreen, wintergreen, and rheumatism root in English. In Tsalagi ᏣᎳᎩ (Cherokee) it is known as ᎠᏨᎩ ᎢᎾᎨᎡᎯ (ahtsvgị ịnạgeẹhi). This species is distinctive in that it has prominent white midribs on the leaves. It is definitely prominent in use in Appalachian ethnobotany. C. menziesii (Menzies' wintergreen, little prince's plume) is generally smaller and has only 1–3 flowers per stem. Given its smaller distribution and physical size it is clearly less-often used.

All species of Chimaphila, though sometimes called wintergreen (because they are evergreen), should be distinguished from true wintergreen, Gaultheria procumbens, which has strongly scented leaves and bell-shaped white flowers.

C. japonica (喜冬草 xǐ dōng cǎo, "winter-loving plant") is found in forested mountain areas in Japan, Korea, China, and Russia. C. monticola (川西喜冬草 chuān xī xǐ dōng cǎo, "Kawanishi winter-loving plant") is found in central China and Taiwan. It is unclear to what extent either is used as medicine.

All species of Chimaphila, though sometimes called wintergreen (because they are evergreen), should be distinguished from true wintergreen, Gaultheria procumbens, which has strongly scented leaves and bell-shaped white flowers.

C. japonica (喜冬草 xǐ dōng cǎo, "winter-loving plant") is found in forested mountain areas in Japan, Korea, China, and Russia. C. monticola (川西喜冬草 chuān xī xǐ dōng cǎo, "Kawanishi winter-loving plant") is found in central China and Taiwan. It is unclear to what extent either is used as medicine.

Advanced Clinical Information

Additional Actions:

In an in vitro assay of hydroethanolic extracts of 18 native plant species from northern Ontario, pipsissewa whole plant was in the top two strongest against Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Microsporum gypseum, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, with activity comparable to pure berberine (Jones, et al. 2000). Prior studies with 1,4-naphthoquinones such as found in pipsissewa (e.g. chimaphilin) have shown their antifungal activity and mechanisms of action (Steffen and Peschel 1975). Indeed, one bioassay-guided assessment found that chimaphilin was the most potent antifungal element in pipsissewa in vitro, acting against multiple targets in the cell wall, mitochondria, DNA transcription, and various metabolic functions (Galván, et al. 2008).

Additional Indications:

The European proprietary formula Eviprostat, which contains 20% pipsissewa, has been shown beneficial for patients with BPH (Tamaki, et al. 2008). This may be related to the formula's antioxidant and inflammation-modulating properties (Oka, et al. 2007).

Many older texts list pipsissewa as a diuretic (Felter 1922; Ellingwood 1919). Others are not so certain of this (Nevins 1851). Some early sources are quite insistent about this, for example, stating that, "Chimaphila is a tonic, astringent diuretic belonging to the same class as Buchu, Uva Ursi, Pareira, and Scoparius. It is probably the most active diuretic among this group, stimulating all the excretory organs but especially the kidneys...Chimaphila is a good diuretic in dropsy, and is efficient in several forms of chronic kidney disease...It is believed to check the secretion of uric acid, and should prove useful in gout and rheumatism" (Potter 1902). However, pipsissewa has not been evaluated as a diuretic in any study that could be identified. An infusion of the leaves of pipsissewa's close cousin Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (uva ursi) was found to not have any diuretic or aquaretic effects in a rat study (Grases, et al. 1994).

- Antioxidant (Galván, et al. 2008)

- Antifungal (Galván, et al. 2008; Jones, et al. 2000; Sheth, et al. 1967)

- Antineoplastic (Fera, et al. 2010)

- Osteoclast differentiation inhibition (Shin, et al. 2015)

In an in vitro assay of hydroethanolic extracts of 18 native plant species from northern Ontario, pipsissewa whole plant was in the top two strongest against Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Microsporum gypseum, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, with activity comparable to pure berberine (Jones, et al. 2000). Prior studies with 1,4-naphthoquinones such as found in pipsissewa (e.g. chimaphilin) have shown their antifungal activity and mechanisms of action (Steffen and Peschel 1975). Indeed, one bioassay-guided assessment found that chimaphilin was the most potent antifungal element in pipsissewa in vitro, acting against multiple targets in the cell wall, mitochondria, DNA transcription, and various metabolic functions (Galván, et al. 2008).

Additional Indications:

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)

The European proprietary formula Eviprostat, which contains 20% pipsissewa, has been shown beneficial for patients with BPH (Tamaki, et al. 2008). This may be related to the formula's antioxidant and inflammation-modulating properties (Oka, et al. 2007).

Many older texts list pipsissewa as a diuretic (Felter 1922; Ellingwood 1919). Others are not so certain of this (Nevins 1851). Some early sources are quite insistent about this, for example, stating that, "Chimaphila is a tonic, astringent diuretic belonging to the same class as Buchu, Uva Ursi, Pareira, and Scoparius. It is probably the most active diuretic among this group, stimulating all the excretory organs but especially the kidneys...Chimaphila is a good diuretic in dropsy, and is efficient in several forms of chronic kidney disease...It is believed to check the secretion of uric acid, and should prove useful in gout and rheumatism" (Potter 1902). However, pipsissewa has not been evaluated as a diuretic in any study that could be identified. An infusion of the leaves of pipsissewa's close cousin Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (uva ursi) was found to not have any diuretic or aquaretic effects in a rat study (Grases, et al. 1994).

Botanical Information

Botanical Description: This perennial herb grows up to 35 cm tall and often grows in mats that extend by creeping rhizomes. It has opposite and some whorled leaves. They are evergreen, leathery, and verdant green with toothed margins. The flowers have 5 green sepals and 5 white or pink/purplish petals that droop downward in umbel-like clusters of 3–8 per stem. Forms a dry, brown, 5-chambered capsule as a fruit. In part because of its distinctly different flower morphology this used to be in the family Pyrolaceae, but genetic research has concluded this genus is part of the Ericaceae (which mostly has urceolate or bell-shaped flowers) (Kron 1996). It is part of the subfamily Pyroloideae along with Pyrola (wintergreens), Moneses (one-flowered wintergreens), and Orthilia (one-sided wintergreens). As with others in this subfamily, it is mixotrophic, fixing carbon from the atmosphere via photosynthesis while also receiving it from fungal mycorrhiza in the soil (Lallemand, et al. 2017; Hynson, et la. 2012; Selosse and Boy 2009).

Native range: This plant is naturally found throughout the temperate Northern Hemisphere (circumboreal distribution). It is found across most of Canada, most northern states in the USA, throughout the mountainous Southwest in the USA, and throughout New England extending as far south as North Carolina. It grows in forested areas.

Chimaphila originally evolved in North America in the early Miocene, sometime between 32.3–8.6 million years ago (Liu, et al. 2019). This appears to have spurred by cooling in its local climate. While C. umbellata appeared to adapt to this climate and moved into a circumboreal distribution, all four other species in the genus moved southward and became endemic to one continent (North America or Eurasia).

Native range: This plant is naturally found throughout the temperate Northern Hemisphere (circumboreal distribution). It is found across most of Canada, most northern states in the USA, throughout the mountainous Southwest in the USA, and throughout New England extending as far south as North Carolina. It grows in forested areas.

Chimaphila originally evolved in North America in the early Miocene, sometime between 32.3–8.6 million years ago (Liu, et al. 2019). This appears to have spurred by cooling in its local climate. While C. umbellata appeared to adapt to this climate and moved into a circumboreal distribution, all four other species in the genus moved southward and became endemic to one continent (North America or Eurasia).

Harvest, Cultivation, and Ecology

Cultivation: There is no significant cultivation of pipsissewa.

Wildcrafting: Pipsissewa is entirely gathered from the wild. As noted below, it may be overharvested primarily for food use.

Ecological Status: Pipsissewa is considered common, widespread, and generally secure, status G5, by NatureServe. However, it is a slow-growing plant and may be undergoing overharvesting to flavor Pepsi™, so care should be taken in harvesting this plant (Russo and Dougherty 2004).

Wildcrafting: Pipsissewa is entirely gathered from the wild. As noted below, it may be overharvested primarily for food use.

Ecological Status: Pipsissewa is considered common, widespread, and generally secure, status G5, by NatureServe. However, it is a slow-growing plant and may be undergoing overharvesting to flavor Pepsi™, so care should be taken in harvesting this plant (Russo and Dougherty 2004).

References

Baker MA (1981) The Ethnobotany of the Yurok, Tolowa and Karok Indians of Northwest California (Humboldt State University, MA Thesis).

Bishop CJ, MacDonald RE (1951) "A survey of higher plants for antibacterial substances" Canadian J Botany 29(3):260–269.

Blaut M, Braune A, Wunderlich S, et al. (2006) "Mutagenicity of arbutin in mammalian cells after activation by human intestinal bacteria" Food Chem Toxicol 44(11):1940–1947.

Chandler RF, Freeman L, Hooper SN (1979) "Herbal remedies of the Maritime Indians" J Ethnopharmacol 1:49–68.

Cook WH (1869) Physio-Medical Dispensatory: A Treatise on Therapeutics, Materia Medica, and Pharmacy in Accordance With the Principles of Physiological Medictaion (Cincinnati: Self-Published) Reprinted at medherb.com.

Crellin JK, Philpott J (1990) A Reference Guide to Medicinal Plants: Herbal Medicine Past and Present (Durham: Duke University Press).

Densmore F (1932) "Menominee music" SI-BAE Bulletin #102.

Densmore F (1928) "Uses of plants by the Chippewa Indians" SI-BAE Annual Report 44:273–379.

Ellingwood F (1919) American Materia Medica, Pharmacognosy and Therapeutics 11th ed (Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, reprinted 1998).

Felter HW (1922) Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, reprinted 1998).

Felter HW, Lloyd JU (1898) King's American Dispensatory, 18th ed; 3rd revision, I & II. Cincinnati: Ohio Valley

Fera J, Lafrenie R, Abou-Zaid M, Arnason JT (2010) "Anti-cancer and chemopreventative activity of Chimaphila umbellata" Pharm Biol 48(suppl 1):27 [abstract].

Galván IJ, Mir-Rashed N, Jessulat M, et al. (2008) "Antifungal and antioxidant activities of the phytomedicine pipsissewa, Chimaphila umbellata" Phytochemistry 69(3):738–746.

Gilmore MR (1933) Some Chippewa Uses of Plants (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press).

Grases F, Melero G, Costa-Bauzá A, et al. (1994) "Urolithiasis and phytotherapy" Int Urol Nephrol 26(5):507–511.

Griffith RE (1847) Medical Botany (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard).

Hart J (1992) Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press).

Hausen BM, Schiedermair I (1988) "The sensitizing capacity of chimaphilin, a naturally-occurring quinone" Contact Dermatitis 19(3):180–183.

Herrick JW (1977) Iroquois Medical Botany (State University of New York, Albany, PhD Thesis).

Hoffmann D (2003) Medical Herbalism: Principles and Practice (Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press)

Hunn ES (1990) Nch'i-Wana, "The Big River": Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

Hynson NA, Mambelli S, Amend AS, Dawson TE (2012) "Measuring carbon gains from fungal networks in understory plants from the tribe Pyroleae (Ericaceae): A field manipulation and stable isotope approach" Oecologia 169(2):307–317.

Johnston A (1987) Plants and the Blackfoot (Lethbridge, Alberta: Lethbridge Historical Society).

Kron KA (1996) "Phylogenetic relationships of Empetraceae, Epacridaceae, Ericaceae, Monotropaceae, and Pyrolaceae: Evidence from nuclear ribosomal 18s sequence data" Ann Botany 77(4):293–304.

Lallemand F, Puttsepp Ü, Lang M, et al. (2017) "Mixotrophy in Pyroleae (Ericaceae) from Estonian boreal forests does not vary with light or tissue age" Ann Bot 120(3):361–71.

Leighton AL (1985) Wild Plant Use by the Woods Cree (Nihithawak) of East-Central Saskatchewan (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. Mercury Series).

Liu ZW, Zhou J, Peng H, et al. (2019) "Relationships between Tertiary relict and circumboreal woodland floras: A case study in Chimaphila (Ericaceae)" Ann Bot 123(6):1089–1098.

McClintock W (1909) "Medizinal- und Nutzpflanzen Der Schwarzfuss Indianer" Z Ethnologie 41:273–279.

Mechling WH (1959) "The Malecite Indians With notes on the Micmacs" Anthropologica 8:239–263.

Mills S (1991) Out of the Earth: The Essential Book of Herbal Medicine (New York: Viking Arkana).

Nevins JB (1851) A translation of the New London Pharmacopœia, including the New Dublin and Edinburgh Pharmacopœias, with a Full Account of Chemical and Medicinal Properties of Their Contents; Forming a Complete Materia Medica (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans).

Oka M, Tachibana M, Noda K, et al. (2007) "Relevance of anti-reactive oxygen species activity to anti-inflammatory activity of components of Eviprostat(R), a phytotherapeutic agent for benign prostatic hyperplasia" Phytomedicine 14(7–8):465–472.

Perry F (1952) "Ethno-Botany of the Indians in the Interior of British Columbia" Museum and Art Notes 2(2):36-43.

Pereira J (1842) Elements of Materia Medica and Therapeutics, 2nd ed, Vols 1 & 2. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans

Piffard HG (1881) A Treatise on the Materia Medica and Therapeutics of the Skin (New York: William Wood & Company).

Potter S (1902) A Handbook of Materia Medica, Pharmacy, and Therapeutics: Including the Physiological Action of Drugs, the Special Therapeutics of Disease, Official and Practical Pharmacy, and Minute Directions for Prescription Writing (P. Blakiston's Son and Company).

Rousseau J (1947) "Ethnobotanique Abenakise" Archives de Folklore 11:145–182 [in French].

Rousseau J (1948) "Ethnobotanique et ethnozoologie Gaspesiennes" Archives de Folklore 3:51–64 [in French].

Russo EB, Dougherty A (2004) Herbal Voices: American Herbalism Through the Words of American Herbalists (Abingdon, UK: Routledge).

Schenck SM, Gifford EW (1952) "Karok Ethnobotany" Anthropological Records 13(6):377–392.

Schindler G, Patzak U, Brinkhaus B, et al. (2002) "Urinary excretion and metabolism of arbutin after oral administration of Arctostaphylos uvae ursi extract as film-coated tablets and aqueous solution in healthy humans" J Clin Pharmacol 42(8):920–927.

Schwartz L, Tulipan L, Peck SM (1947) Occupational Diseases of the Skin. 2nd ed (London: Henry Kimpton).

Selosse MA, Roy M (2009) "Green plants that feed on fungi: Facts and questions about mixotrophy" Trends Plant Sci 14(2):64–70.

Sheth K, Catalfomo P, Sciuchetti LA, French DH (1967) "Phytochemical Investigation of the leaves of Chimaphila umbellata" Lloydia 30:78–83.

Shin BK, Kim J, Kang KS, et al. (2015) "A new naphthalene glycoside from Chimaphila umbellata inhibits the RANKL-stimulated osteoclast differentiation" Arch Pharm Res 38(11):2059–2065.

Smith HH (1923) "Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians" Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:1–174.

Speck FG (1917) "Medicine Practices of the Northeastern Algonquians" Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Americanists:303–321.

Speck FG, Hassrick RB, Carpenter ES (1942) "Rappahannock Herbals, Folk-Lore and Science of Cures" Proceedings of the Delaware County Institute of Science 10:7–55.

Steedman EV (1928) "The ethnobotany of the Thompson Indians of British Columbia" SI-BAE Annual Report 45:441–522.

Steffen K, Peschel H (1975) "Chemical constitution and antifungal activity of 1,4-naphthoquinones, their biosynthetic intermediary products and chemical related compounds" Planta Med 27(3):201–212 [in German].

Takahashi H (1986) "Pollen polyads and their variation in Chimaphila (Pyrolaceae)" Grana 25(3):161–169.

Tamaki M, Nakashima M, Nishiyama R, et al. (2008) "Assessment of clinical usefulness of Eviprostat for benign prostatic hyperplasia–-comparison of Eviprostat tablet with a formulation containing two-times more active ingredients" Hinyokika Kiyo 54(6):435–445 [in Japanese].

Tantaquidgeon G (1928) "Mohegan medicinal practices, weather-lore and superstitions" SI-BAE Annual Report 43:264–270.

Tantaquidgeon G (1942) A Study of Delaware Indian Medicine Practice and Folk Beliefs (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical Commission).

Tantaquidgeon G (1972) Folk Medicine of the Delaware and Related Algonkian Indians (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical Commission Anthropological Papers \#3).

Taylor LA (1940) Plants Used As Curatives by Certain Southeastern Tribes (Cambridge, MA: Botanical Museum of Harvard University).

Trubachev AA, Batiuk VS (1969) "Phytochemical study of Chimaphila umbellata (L) Nutt" Farmatsiia 18(3):48–51 [in Russian].

Turner NC, Bell MAM (1971) "The ethnobotany of the Coast Salish Indians of Vancouver Island" Econ Botany 25(1):63–104.

Turner NJ, Bouchard R, Kennedy DID (1980) Ethnobotany of the Okanagan-Colville Indians of British Columbia and Washington (Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Museum).

USDA; Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases. Plants with a chosen chemical. Arbutin. Washington, DC: US Dept Agric, Agric Res Service. Available from the database query page at \url{http://www.ars-grin.gov/duke/ [accessed 4 Nov 2008].

Vandal J, Abou-Zaid MM, Ferroni G, Leduc LG (2015) "Antimicrobial activity of natural products from the flora of Northern Ontario, Canada" Pharm Biol 53(6):800–806.

Walewska E, Thieme H (1969) "Isolation of isohomoarbutin from Chimaphila umbellata (L) Barton" Pharmazie 24(7):423 [in German].

White JC (1887) Dermatitis Venenata: An account of the action of external irritants upon the skin (Boston: Cupples and Hurd).

Bishop CJ, MacDonald RE (1951) "A survey of higher plants for antibacterial substances" Canadian J Botany 29(3):260–269.

Blaut M, Braune A, Wunderlich S, et al. (2006) "Mutagenicity of arbutin in mammalian cells after activation by human intestinal bacteria" Food Chem Toxicol 44(11):1940–1947.

Chandler RF, Freeman L, Hooper SN (1979) "Herbal remedies of the Maritime Indians" J Ethnopharmacol 1:49–68.

Cook WH (1869) Physio-Medical Dispensatory: A Treatise on Therapeutics, Materia Medica, and Pharmacy in Accordance With the Principles of Physiological Medictaion (Cincinnati: Self-Published) Reprinted at medherb.com.

Crellin JK, Philpott J (1990) A Reference Guide to Medicinal Plants: Herbal Medicine Past and Present (Durham: Duke University Press).

Densmore F (1932) "Menominee music" SI-BAE Bulletin #102.

Densmore F (1928) "Uses of plants by the Chippewa Indians" SI-BAE Annual Report 44:273–379.

Ellingwood F (1919) American Materia Medica, Pharmacognosy and Therapeutics 11th ed (Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, reprinted 1998).

Felter HW (1922) Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, reprinted 1998).

Felter HW, Lloyd JU (1898) King's American Dispensatory, 18th ed; 3rd revision, I & II. Cincinnati: Ohio Valley

Fera J, Lafrenie R, Abou-Zaid M, Arnason JT (2010) "Anti-cancer and chemopreventative activity of Chimaphila umbellata" Pharm Biol 48(suppl 1):27 [abstract].

Galván IJ, Mir-Rashed N, Jessulat M, et al. (2008) "Antifungal and antioxidant activities of the phytomedicine pipsissewa, Chimaphila umbellata" Phytochemistry 69(3):738–746.

Gilmore MR (1933) Some Chippewa Uses of Plants (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press).

Grases F, Melero G, Costa-Bauzá A, et al. (1994) "Urolithiasis and phytotherapy" Int Urol Nephrol 26(5):507–511.

Griffith RE (1847) Medical Botany (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard).

Hart J (1992) Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press).

Hausen BM, Schiedermair I (1988) "The sensitizing capacity of chimaphilin, a naturally-occurring quinone" Contact Dermatitis 19(3):180–183.

Herrick JW (1977) Iroquois Medical Botany (State University of New York, Albany, PhD Thesis).

Hoffmann D (2003) Medical Herbalism: Principles and Practice (Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press)

Hunn ES (1990) Nch'i-Wana, "The Big River": Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

Hynson NA, Mambelli S, Amend AS, Dawson TE (2012) "Measuring carbon gains from fungal networks in understory plants from the tribe Pyroleae (Ericaceae): A field manipulation and stable isotope approach" Oecologia 169(2):307–317.

Johnston A (1987) Plants and the Blackfoot (Lethbridge, Alberta: Lethbridge Historical Society).

Kron KA (1996) "Phylogenetic relationships of Empetraceae, Epacridaceae, Ericaceae, Monotropaceae, and Pyrolaceae: Evidence from nuclear ribosomal 18s sequence data" Ann Botany 77(4):293–304.

Lallemand F, Puttsepp Ü, Lang M, et al. (2017) "Mixotrophy in Pyroleae (Ericaceae) from Estonian boreal forests does not vary with light or tissue age" Ann Bot 120(3):361–71.

Leighton AL (1985) Wild Plant Use by the Woods Cree (Nihithawak) of East-Central Saskatchewan (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. Mercury Series).

Liu ZW, Zhou J, Peng H, et al. (2019) "Relationships between Tertiary relict and circumboreal woodland floras: A case study in Chimaphila (Ericaceae)" Ann Bot 123(6):1089–1098.

McClintock W (1909) "Medizinal- und Nutzpflanzen Der Schwarzfuss Indianer" Z Ethnologie 41:273–279.

Mechling WH (1959) "The Malecite Indians With notes on the Micmacs" Anthropologica 8:239–263.

Mills S (1991) Out of the Earth: The Essential Book of Herbal Medicine (New York: Viking Arkana).

Nevins JB (1851) A translation of the New London Pharmacopœia, including the New Dublin and Edinburgh Pharmacopœias, with a Full Account of Chemical and Medicinal Properties of Their Contents; Forming a Complete Materia Medica (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans).

Oka M, Tachibana M, Noda K, et al. (2007) "Relevance of anti-reactive oxygen species activity to anti-inflammatory activity of components of Eviprostat(R), a phytotherapeutic agent for benign prostatic hyperplasia" Phytomedicine 14(7–8):465–472.

Perry F (1952) "Ethno-Botany of the Indians in the Interior of British Columbia" Museum and Art Notes 2(2):36-43.

Pereira J (1842) Elements of Materia Medica and Therapeutics, 2nd ed, Vols 1 & 2. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans

Piffard HG (1881) A Treatise on the Materia Medica and Therapeutics of the Skin (New York: William Wood & Company).

Potter S (1902) A Handbook of Materia Medica, Pharmacy, and Therapeutics: Including the Physiological Action of Drugs, the Special Therapeutics of Disease, Official and Practical Pharmacy, and Minute Directions for Prescription Writing (P. Blakiston's Son and Company).

Rousseau J (1947) "Ethnobotanique Abenakise" Archives de Folklore 11:145–182 [in French].

Rousseau J (1948) "Ethnobotanique et ethnozoologie Gaspesiennes" Archives de Folklore 3:51–64 [in French].

Russo EB, Dougherty A (2004) Herbal Voices: American Herbalism Through the Words of American Herbalists (Abingdon, UK: Routledge).

Schenck SM, Gifford EW (1952) "Karok Ethnobotany" Anthropological Records 13(6):377–392.

Schindler G, Patzak U, Brinkhaus B, et al. (2002) "Urinary excretion and metabolism of arbutin after oral administration of Arctostaphylos uvae ursi extract as film-coated tablets and aqueous solution in healthy humans" J Clin Pharmacol 42(8):920–927.

Schwartz L, Tulipan L, Peck SM (1947) Occupational Diseases of the Skin. 2nd ed (London: Henry Kimpton).

Selosse MA, Roy M (2009) "Green plants that feed on fungi: Facts and questions about mixotrophy" Trends Plant Sci 14(2):64–70.

Sheth K, Catalfomo P, Sciuchetti LA, French DH (1967) "Phytochemical Investigation of the leaves of Chimaphila umbellata" Lloydia 30:78–83.

Shin BK, Kim J, Kang KS, et al. (2015) "A new naphthalene glycoside from Chimaphila umbellata inhibits the RANKL-stimulated osteoclast differentiation" Arch Pharm Res 38(11):2059–2065.

Smith HH (1923) "Ethnobotany of the Menomini Indians" Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 4:1–174.

Speck FG (1917) "Medicine Practices of the Northeastern Algonquians" Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Americanists:303–321.

Speck FG, Hassrick RB, Carpenter ES (1942) "Rappahannock Herbals, Folk-Lore and Science of Cures" Proceedings of the Delaware County Institute of Science 10:7–55.

Steedman EV (1928) "The ethnobotany of the Thompson Indians of British Columbia" SI-BAE Annual Report 45:441–522.

Steffen K, Peschel H (1975) "Chemical constitution and antifungal activity of 1,4-naphthoquinones, their biosynthetic intermediary products and chemical related compounds" Planta Med 27(3):201–212 [in German].

Takahashi H (1986) "Pollen polyads and their variation in Chimaphila (Pyrolaceae)" Grana 25(3):161–169.

Tamaki M, Nakashima M, Nishiyama R, et al. (2008) "Assessment of clinical usefulness of Eviprostat for benign prostatic hyperplasia–-comparison of Eviprostat tablet with a formulation containing two-times more active ingredients" Hinyokika Kiyo 54(6):435–445 [in Japanese].

Tantaquidgeon G (1928) "Mohegan medicinal practices, weather-lore and superstitions" SI-BAE Annual Report 43:264–270.

Tantaquidgeon G (1942) A Study of Delaware Indian Medicine Practice and Folk Beliefs (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical Commission).

Tantaquidgeon G (1972) Folk Medicine of the Delaware and Related Algonkian Indians (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical Commission Anthropological Papers \#3).

Taylor LA (1940) Plants Used As Curatives by Certain Southeastern Tribes (Cambridge, MA: Botanical Museum of Harvard University).

Trubachev AA, Batiuk VS (1969) "Phytochemical study of Chimaphila umbellata (L) Nutt" Farmatsiia 18(3):48–51 [in Russian].

Turner NC, Bell MAM (1971) "The ethnobotany of the Coast Salish Indians of Vancouver Island" Econ Botany 25(1):63–104.

Turner NJ, Bouchard R, Kennedy DID (1980) Ethnobotany of the Okanagan-Colville Indians of British Columbia and Washington (Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Museum).

USDA; Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases. Plants with a chosen chemical. Arbutin. Washington, DC: US Dept Agric, Agric Res Service. Available from the database query page at \url{http://www.ars-grin.gov/duke/ [accessed 4 Nov 2008].

Vandal J, Abou-Zaid MM, Ferroni G, Leduc LG (2015) "Antimicrobial activity of natural products from the flora of Northern Ontario, Canada" Pharm Biol 53(6):800–806.

Walewska E, Thieme H (1969) "Isolation of isohomoarbutin from Chimaphila umbellata (L) Barton" Pharmazie 24(7):423 [in German].

White JC (1887) Dermatitis Venenata: An account of the action of external irritants upon the skin (Boston: Cupples and Hurd).