by Eric Yarnell, ND, RH(AHG)

Last updated 16 Jan 2022

This monograph is protected by copyright and is intended only for use by health care professionals and students. You may link to this page if you are sharing it with others in health care, but may not otherwise copy, alter, or share this material in any way. By accessing this material you agree to hold the author harmless for any use of this information. Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site.

Table of Contents

Clinical Highlights

Two major species covered:

E. angustifolium Nutt

E. californicum (Hook & Arn) Torr

Yerba santa is used primarily for people with respiratory tract infections.

Yerba santa is a inflammation modulator and relaxing expectorant.

Yerba santa is gentle in its action and usually has no adverse effects.

The medicinal taste of yerba santa is a good cover for bitter medicines (i.e. it is corrigent).

E. angustifolium Nutt

E. californicum (Hook & Arn) Torr

Yerba santa is used primarily for people with respiratory tract infections.

Yerba santa is a inflammation modulator and relaxing expectorant.

Yerba santa is gentle in its action and usually has no adverse effects.

The medicinal taste of yerba santa is a good cover for bitter medicines (i.e. it is corrigent).

Clinical Fundamentals

Part Used: Fresh leaf from new growth of plant gathered just before flowering is the most common part used. Dried leaf can also be used but is not as potent.

Taste: Aromatic, resinous, medicinal, and slightly bitter. The flavor is quite distinctive and unlikely to be mistaken for anything else.

Major Actions:

These actions primarily occur in the respiratory tract. Yerba santa helps the inflammatory process heal without causing as much damage to healthy tissues, moderating symptoms while still allowing the disease process to be resolved. The herb is particularly useful when there is an accompanying spasmodic cough (as a relaxing expectorant) and particularly when there is thick, sticky mucus, which is it loosens (as a mucolytic). I would rate Grindelia spp (gumweed) and Populus spp (cottonwood) buds as more potent mucolytics, but yerba santa as the most palatable by far.

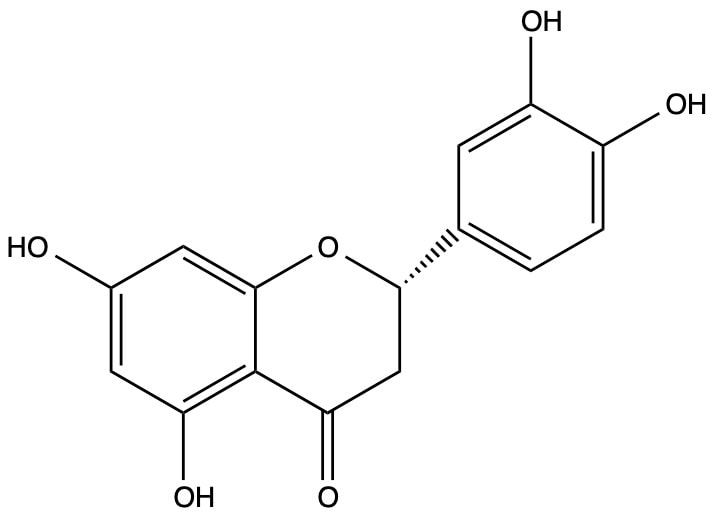

One in vitro study found eriodictyol inhibited mast cell degranulation (Yoo, et al. 2012). Other research suggests it acts specifically by inhibiting the JNK inflammatory pathway (Lee, et al. 2013). Eriodictyol has many beneficial effects on atopic dermatitis in mice (Park, et al. 2013).

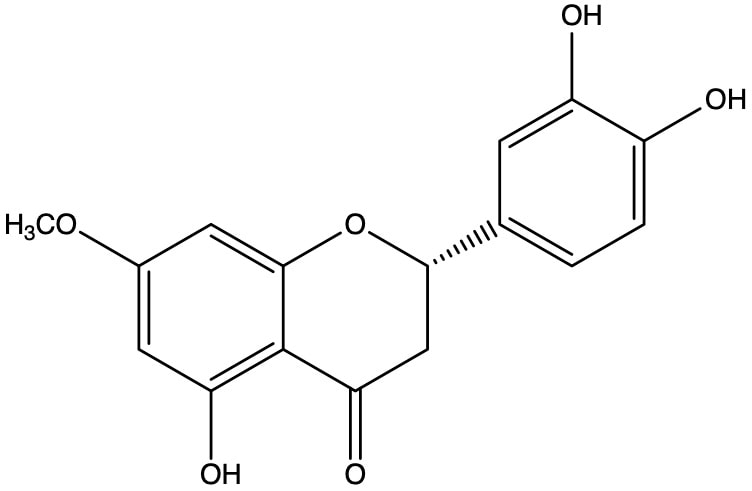

In one older study, yerba santa tincture was found to be the most effective at masking the taste of bitter tinctures (Ward and Munch 1930). Follow-up work recently found that a sodium salt of homoeriodictyol was quite effective at masking bitter tastes, particularly those due to caffeine and amarogentin (Ley, et al. 2005). The magnitude of masking was judged to be as high as 40%. Flavonoids from E. californicum have been shown to be antagonists of bitter receptors (Fletcher, et al. 2011). The flavanone homoeriodicytol has specifically been shown to have corrigent effects (Reichelt, et al. 2010).

Major Organ System Affinities:

Major Indications:

Major Constituents:

Adverse Effects: None

E. parryi (poodle-dog bush) can cause severe contact dermatitis with blistering that may last as long as several weeks, in significant part due to the presence of derivatives of farnesyl hydroquinone and 3-farnesyl-P-hydroxybenzoic acid in its glandular trichomes (Reynolds, et al. 1985). These sticky hairs can stick to clothing and animal fur, and spread to others who haven't even touched the plant. The rash may not start until days after exposure.

Contraindications: None

Drug Interactions: There are no such interactions documented or suspected.

Taste: Aromatic, resinous, medicinal, and slightly bitter. The flavor is quite distinctive and unlikely to be mistaken for anything else.

Major Actions:

- Inflammation modulating (Lee, et al. 2013; Yoo, et al. 2012)

- Mucolytic, moderately potent.

- Anti-allergic (Park, et al. 2013; Yoo, et al. 2012)

- Relaxing expectorant

- Corrigent (flavor-enhancing) (Ward and Munch 1930; Lewin 1894; Rother 1887)

These actions primarily occur in the respiratory tract. Yerba santa helps the inflammatory process heal without causing as much damage to healthy tissues, moderating symptoms while still allowing the disease process to be resolved. The herb is particularly useful when there is an accompanying spasmodic cough (as a relaxing expectorant) and particularly when there is thick, sticky mucus, which is it loosens (as a mucolytic). I would rate Grindelia spp (gumweed) and Populus spp (cottonwood) buds as more potent mucolytics, but yerba santa as the most palatable by far.

One in vitro study found eriodictyol inhibited mast cell degranulation (Yoo, et al. 2012). Other research suggests it acts specifically by inhibiting the JNK inflammatory pathway (Lee, et al. 2013). Eriodictyol has many beneficial effects on atopic dermatitis in mice (Park, et al. 2013).

In one older study, yerba santa tincture was found to be the most effective at masking the taste of bitter tinctures (Ward and Munch 1930). Follow-up work recently found that a sodium salt of homoeriodictyol was quite effective at masking bitter tastes, particularly those due to caffeine and amarogentin (Ley, et al. 2005). The magnitude of masking was judged to be as high as 40%. Flavonoids from E. californicum have been shown to be antagonists of bitter receptors (Fletcher, et al. 2011). The flavanone homoeriodicytol has specifically been shown to have corrigent effects (Reichelt, et al. 2010).

Major Organ System Affinities:

- Respiratory tract

Major Indications:

- Acute upper respiratory tract infections

- Acute bronchitis

- Spasmodic cough

- Chronic lung inflammations, especially asthma

- Acute asthma (especially smoked)

Major Constituents:

- Resin

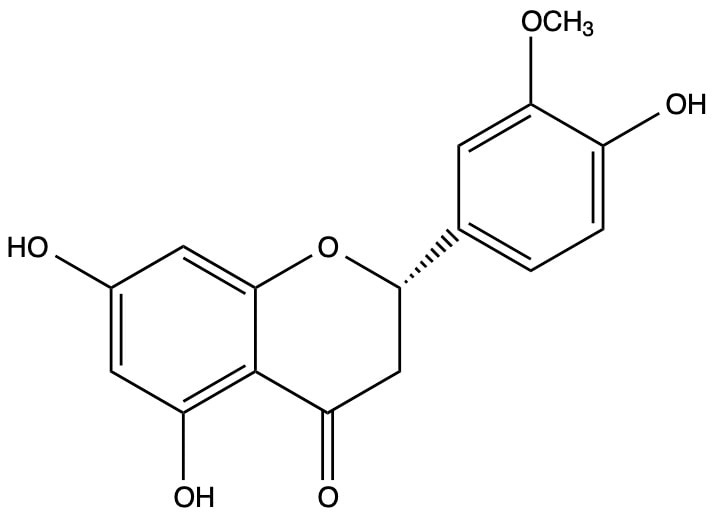

- Flavonoid glycosides (e.g. eriodictyol, homoeriodictyol, sterubin)

Adverse Effects: None

E. parryi (poodle-dog bush) can cause severe contact dermatitis with blistering that may last as long as several weeks, in significant part due to the presence of derivatives of farnesyl hydroquinone and 3-farnesyl-P-hydroxybenzoic acid in its glandular trichomes (Reynolds, et al. 1985). These sticky hairs can stick to clothing and animal fur, and spread to others who haven't even touched the plant. The rash may not start until days after exposure.

Contraindications: None

Drug Interactions: There are no such interactions documented or suspected.

Pharmacy Essentials

Tincture: 1:2–1:3 w:v ratio, 70–90% ethanol

Acute, adult: 4–6 ml every 2–3 h, adjusted for body size

Chronic, adult: 3–6 ml tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Infusion: this is not as effective compared to tincture or crude herb since its resins are not water soluble, though its flavonoids are. Use 5–10 g per 250 ml water, steep 15 minutes covered, and this makes one cup (not 8 oz but one dose). The amount of water can be adjusted by the patient to taste after the first cup if prepared.

Crude dried herb, smoked: for acute asthma, usually mixed with Datura or Lobelia. Of an equal mixture of these three 1 tsp is smoked.

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Acute, adult: 4–6 ml every 2–3 h, adjusted for body size

Chronic, adult: 3–6 ml tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Infusion: this is not as effective compared to tincture or crude herb since its resins are not water soluble, though its flavonoids are. Use 5–10 g per 250 ml water, steep 15 minutes covered, and this makes one cup (not 8 oz but one dose). The amount of water can be adjusted by the patient to taste after the first cup if prepared.

Crude dried herb, smoked: for acute asthma, usually mixed with Datura or Lobelia. Of an equal mixture of these three 1 tsp is smoked.

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Other Names

Latin Synonyms:

Eriodictyon angustifolium var amplifolium Brand

Eriodictyon angustifolium var pubens A Gray

Eriodictyon glutinosum var angustifolium (Nutt) Torr

Eriodictyon californicum subvar coarctatum Brand

Wigandia californica Hook et Arn

Eriodictyon californicum f latifolia Brand

Eriodictyon californicum f linearis Brand

Eriodictyon californicum ssp australe Brand

Eriodictyon californicum ssp glutinosum (Benth) Brand

Eriodictyon californicum var pubens Brand

Eriodictyon glutinosum Benth

Eriodictyon glutinosum var serratum Choisy

Other Common Names:

(see table below)

Eriodictyon angustifolium var amplifolium Brand

Eriodictyon angustifolium var pubens A Gray

Eriodictyon glutinosum var angustifolium (Nutt) Torr

Eriodictyon californicum subvar coarctatum Brand

Wigandia californica Hook et Arn

Eriodictyon californicum f latifolia Brand

Eriodictyon californicum f linearis Brand

Eriodictyon californicum ssp australe Brand

Eriodictyon californicum ssp glutinosum (Benth) Brand

Eriodictyon californicum var pubens Brand

Eriodictyon glutinosum Benth

Eriodictyon glutinosum var serratum Choisy

Other Common Names:

(see table below)

| Latin | English | Cham'teela (Luiseño) |

| Eriodicyton angustifolium | narrow-leaf yerba santa | -- |

| Eriodictyon californicum | California yerba santa, mountain balm, consumptive's weed, bear weed, gum plant, tarweed | pálvonkut |

| Eriodictyon crassifolium | California thick-leaved yerba santa | pálwut |

| Eriodictyon parryi | poodle-dog bush | atovikut |

| Eriodictyon tomentosum | woolly yerba santa | pálwut |

| Eriodictyon trichocalyx var lanatum | hairy yerba santa | pálwut |

| Eriodictyon trichocalyx var trichocalyx | mountain balm | pálwut |

Advanced Clinical Information

Additional Actions:

An in vitro study found that E. angustifolium had antimicrobial activity (Dentali and Hoffmann 1992). Antineoplastic agents have been isolated from E. californicum in vitro (Liu, et al. 1992).

Additional Indications:

A recent clinical trial found that E. angustifolium (but not E. caifornicum) extracts reduced gray hair (Taguchi, et al. 2020).

A decoction of the leaves of E. angustifolium was reportedly used by the Hwalbay (Hualapai) people of the desert southwestern US topically for cuts and tired feet and internally for indigestion and as a laxative (Watahomigie 1982). The Paiute reportedly used a decoction or infusion of the leaves for diarrhea, vomiting, colds, coughs, and as an expectorant (including for tuberculosis) (Train, et al. 1941). The Shoshone reportedly used an infusion or decoction of the leaves for indigestion, colds, coughs, tuberculosis, and venereal diseases, while applying a poultice or hot compress of the leaf infusion on joints affected by rheumatism (Train, et al. 1941).

The Atsugé (Atsugewi) people of northeastern California reportedly used E. californicum leaves in a steam for people with rheumatism and crude leaves were chewed for colds and pertussis (Garth 1953). The Ivilyuqaletem (Cahuilla) of southern California reportedly used a decoction of the leaves to wash fatigued limbs and poulticed the leaves on sores (of both humans and animals) (Barrows 1967). The Muwekma (Ohlone) of north and central California reportedly applied a poultice of heated leaves to headaches, used a decoction for rheumatism, to purify the blood, for colds, tuberculosis, as an eyewash, for infected sores, and smoked or chewed the leaves for asthma (Bocek 1984).

The Chumash people of coastal California reportedly used E. crassifolium and E. trichocalyx for many respiratory problems including tuberculosis (Adams and Garcia 2005). The Payómkawichum (Luiseño) people of the desert southwestern US reportedly used the leaves of E. trichocalyx in an infusion as an expectorant (Crouthamel 2009).

Many similar reports abound in the literature, showing that the current clinical uses of yerba santa are firmly rooted in the experience of indigenous peoples of North America.

- Gastrointestinal stimulant

- Antimicrobial (Dentali and Hoffmann 1992; Salle, et al. 1951)

- Antineoplastic (Liu, et al. 1992)

- TRMP3 receptor inhibitor thus analgesic; pure eriodictyol (Straub, et al. 2013)

- β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibition; pure eriodictyol (Hawegawa, et al. 2013)

An in vitro study found that E. angustifolium had antimicrobial activity (Dentali and Hoffmann 1992). Antineoplastic agents have been isolated from E. californicum in vitro (Liu, et al. 1992).

Additional Indications:

- Dyspepsia, indigestion

- Gray hair

- Interstitial cystitis

- Urinary tract infections

A recent clinical trial found that E. angustifolium (but not E. caifornicum) extracts reduced gray hair (Taguchi, et al. 2020).

A decoction of the leaves of E. angustifolium was reportedly used by the Hwalbay (Hualapai) people of the desert southwestern US topically for cuts and tired feet and internally for indigestion and as a laxative (Watahomigie 1982). The Paiute reportedly used a decoction or infusion of the leaves for diarrhea, vomiting, colds, coughs, and as an expectorant (including for tuberculosis) (Train, et al. 1941). The Shoshone reportedly used an infusion or decoction of the leaves for indigestion, colds, coughs, tuberculosis, and venereal diseases, while applying a poultice or hot compress of the leaf infusion on joints affected by rheumatism (Train, et al. 1941).

The Atsugé (Atsugewi) people of northeastern California reportedly used E. californicum leaves in a steam for people with rheumatism and crude leaves were chewed for colds and pertussis (Garth 1953). The Ivilyuqaletem (Cahuilla) of southern California reportedly used a decoction of the leaves to wash fatigued limbs and poulticed the leaves on sores (of both humans and animals) (Barrows 1967). The Muwekma (Ohlone) of north and central California reportedly applied a poultice of heated leaves to headaches, used a decoction for rheumatism, to purify the blood, for colds, tuberculosis, as an eyewash, for infected sores, and smoked or chewed the leaves for asthma (Bocek 1984).

The Chumash people of coastal California reportedly used E. crassifolium and E. trichocalyx for many respiratory problems including tuberculosis (Adams and Garcia 2005). The Payómkawichum (Luiseño) people of the desert southwestern US reportedly used the leaves of E. trichocalyx in an infusion as an expectorant (Crouthamel 2009).

Many similar reports abound in the literature, showing that the current clinical uses of yerba santa are firmly rooted in the experience of indigenous peoples of North America.

Classic Formulas

Michael Moore's Cold and Allergy Formula (Moore 2003b)

Eriodictyon californicum (California yerba santa)

Marrubium vulgare (horehound)

Ephedra nevadensis (Mormon tea)

Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) leaf

Morella cerifera (bayberry)

Balsamorrhiza deltoidea (balsamroot)

He does not give ratios of the herbs in the formula. He says that 1 rounded tablespoon of the finely-chopped herbs should be steeped in a cup of hot water for 10 min, cooled, honey added, and drunk.

Dr. Silena Heron's Allergy-Ease

Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) leaf tincture 21%

Euphrasia rostkoviana = E. officinalis (eyebright) herb tincture 21%

Anemopsis californica (yerba mansa) root tincture 16%

Eriodictyon angustifolium leaf tincture 11%

Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal) root tincture 11%

Ligusticum porteri (oshá) root tincture 10%

Solidago canadensis (goldenrod) flowering tops tincture 7%

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) root fluid extract 3%

Sig: 1 tsp tid

This formula was transmitted to Dr. Yarnell around 1998, having been in use and continually improved (based on patient responses) in the prior 20 years of Dr. Heron's practice. When indicated, and for more serious symptoms, she would add Ephedra sinica (ma huang).

Eriodictyon californicum (California yerba santa)

Marrubium vulgare (horehound)

Ephedra nevadensis (Mormon tea)

Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) leaf

Morella cerifera (bayberry)

Balsamorrhiza deltoidea (balsamroot)

He does not give ratios of the herbs in the formula. He says that 1 rounded tablespoon of the finely-chopped herbs should be steeped in a cup of hot water for 10 min, cooled, honey added, and drunk.

Dr. Silena Heron's Allergy-Ease

Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) leaf tincture 21%

Euphrasia rostkoviana = E. officinalis (eyebright) herb tincture 21%

Anemopsis californica (yerba mansa) root tincture 16%

Eriodictyon angustifolium leaf tincture 11%

Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal) root tincture 11%

Ligusticum porteri (oshá) root tincture 10%

Solidago canadensis (goldenrod) flowering tops tincture 7%

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) root fluid extract 3%

Sig: 1 tsp tid

This formula was transmitted to Dr. Yarnell around 1998, having been in use and continually improved (based on patient responses) in the prior 20 years of Dr. Heron's practice. When indicated, and for more serious symptoms, she would add Ephedra sinica (ma huang).

Monograph from Eclectic Materia Medica (Felter 1922)

ERIODICTYON

The dried leaves of Eriodictyon californicum (Hooker and Arnott), Greene (Nat. Ord. Hydrophyllaceae). A shrubby plant of California and northern Mexico. Dose, 5 to 30 grains.

Common Names.–Yerba Santa, Mountain Balm.

Principal Constituents.–Resin, volatile oil, the glucoside ericolin, and eriodictyonic acid.

Preparation.–Specific Medicine Yerba Santa. Dose, 5 to 30 drops.

Specific Indications.–"Cough with abundant and easy expectoration" (Scudder). "Chronic asthma with cough, profuse expectoration, thickening of the bronchial membrane, loss of appetite, impaired digestion, emaciation" (Watkins).

Action and Therapy.–A stimulating expectorant having a kindly and beneficial action upon digestion. It is to be employed where there are excessive catarrhal discharges of the bronchial and renal tracts. It may be used where there is chronic cough with free secretions, as in chronic bronchitis, bronchorrhea, humid asthma, and the cough of phthisis. Some cases of chronic catarrh of the stomach and catarrhal cystitis have been successfully treated with it.

The dried leaves of Eriodictyon californicum (Hooker and Arnott), Greene (Nat. Ord. Hydrophyllaceae). A shrubby plant of California and northern Mexico. Dose, 5 to 30 grains.

Common Names.–Yerba Santa, Mountain Balm.

Principal Constituents.–Resin, volatile oil, the glucoside ericolin, and eriodictyonic acid.

Preparation.–Specific Medicine Yerba Santa. Dose, 5 to 30 drops.

Specific Indications.–"Cough with abundant and easy expectoration" (Scudder). "Chronic asthma with cough, profuse expectoration, thickening of the bronchial membrane, loss of appetite, impaired digestion, emaciation" (Watkins).

Action and Therapy.–A stimulating expectorant having a kindly and beneficial action upon digestion. It is to be employed where there are excessive catarrhal discharges of the bronchial and renal tracts. It may be used where there is chronic cough with free secretions, as in chronic bronchitis, bronchorrhea, humid asthma, and the cough of phthisis. Some cases of chronic catarrh of the stomach and catarrhal cystitis have been successfully treated with it.

Monograph from A Compend of the New Materia Medica (Cook 1896)

ERIODICTYON GLUTINOSUM

YERBA SANTA, MOUNTAIN BALM, BEAR'S WEED.

Upon the dry hills of California this little shrub grows abundantly. Its leaves are lanceolate, 3 to 6 inches long, thick, and of a somewhat leathery texture, having a resinous feel, smooth above, white with a fine wooliness underneath. The leaves are the medicinal portion, and contain 30 percent or more of a gum resin, a small amount of volatile oil, and some tannin.

Medical Properties.—Yerba Santa (the Holy Herb) was long used by the Spaniards of California and Mexico before it came to professional notice; and the name they gave it suggests the esteem in which it was held by them. In 1873, a friend sent me some of the leaves; and I at once apprehended their character and proceeded to use them with great satisfaction, but had no specimens to enable me to give them their botanical place. A few years later Dr. J. H. Bundy attracted earnest attention to it, and the house of Parke, Davis and Co. aided materially in enlisting the profession toward it.

It is a stimulant with some relaxant properties, of the gum resinous or balsamic class, leaving behind a slightly tonic impression. Its action is moderately prompt and rather persistent; and, like many other balsams, is largely expended on the bronchial mucous surfaces, and on the renal organs and pelvic mucosa to a fair degree. It is most efficacious in bronchial affections, especially in sub-acute and chronic inflammations with severe and spasmodic cough, tickling, scanty and tenacious expectoration, and asthmatic breathing. In all such troubles it is of signal efficacy, securing freer expectoration without relaxing the parts, and affording prompt relief. Among such conditions come bronchorrhoea and the distressing winter cough of elderly persons. Laryngeal congestions are equally amenable to it. Some have commended it in whooping-cough; but I have not found it of much service there, although it makes a suitable addition to castanea when a stimulating expectorant is advisable in the advanced stages. In asthma, it is beneficial by hastening the expulsion of the tenacious mucus, and affords much relief to many cases; and a little lobelia with it makes an effective combination. Smoking the leaves in asthma is a common practice among the natives. Being itself largely stimulating, it may be combined with the relaxing glycyrrhiza, especially when it is necessary to allay the vexatious tickling in the throat that accom- panies many coughs. In cases of phthisis, the yerba santa alone is good for throat tickling; but beyond its influence as a reliable balsamic expectorant, it is not to be depended on in that malady. For chronic coughs with weakness of the respiratory mucous membranes and profuse expectoration, its stimulating and mildly tonic properties make it an admirable article, especially if aided by the antispasmodic and astringent properties of either of the viburnums of hamamelis, or of trillium. In aphonia, and the half-paralyzed condition of the laryngeal muscles of some coughs, it is excellent, alone or with such a stimulant as xanthoxylum. The action of yerba santa on the renal organs deserves more attention than it has received, especially in chronic cystitis and gleet. It makes a fair stimulating addendum to such diuretics as eupatorium purpureum and juniper berries; and to such uterine agents as mitchella and polygonatum for lax conditions of the female organs. Dose of the fluid extract, 5 to 30 drops or more every four or three hours. Its resinous character prevents its being miscible with water; but when a little alkali is added it is more miscible and makes a clear mixture with syrups. Combined with coriander, cinnamon and other aromatics it is used to disguise the bitterness of quinine. It is not compatible with acids.

YERBA SANTA, MOUNTAIN BALM, BEAR'S WEED.

Upon the dry hills of California this little shrub grows abundantly. Its leaves are lanceolate, 3 to 6 inches long, thick, and of a somewhat leathery texture, having a resinous feel, smooth above, white with a fine wooliness underneath. The leaves are the medicinal portion, and contain 30 percent or more of a gum resin, a small amount of volatile oil, and some tannin.

Medical Properties.—Yerba Santa (the Holy Herb) was long used by the Spaniards of California and Mexico before it came to professional notice; and the name they gave it suggests the esteem in which it was held by them. In 1873, a friend sent me some of the leaves; and I at once apprehended their character and proceeded to use them with great satisfaction, but had no specimens to enable me to give them their botanical place. A few years later Dr. J. H. Bundy attracted earnest attention to it, and the house of Parke, Davis and Co. aided materially in enlisting the profession toward it.

It is a stimulant with some relaxant properties, of the gum resinous or balsamic class, leaving behind a slightly tonic impression. Its action is moderately prompt and rather persistent; and, like many other balsams, is largely expended on the bronchial mucous surfaces, and on the renal organs and pelvic mucosa to a fair degree. It is most efficacious in bronchial affections, especially in sub-acute and chronic inflammations with severe and spasmodic cough, tickling, scanty and tenacious expectoration, and asthmatic breathing. In all such troubles it is of signal efficacy, securing freer expectoration without relaxing the parts, and affording prompt relief. Among such conditions come bronchorrhoea and the distressing winter cough of elderly persons. Laryngeal congestions are equally amenable to it. Some have commended it in whooping-cough; but I have not found it of much service there, although it makes a suitable addition to castanea when a stimulating expectorant is advisable in the advanced stages. In asthma, it is beneficial by hastening the expulsion of the tenacious mucus, and affords much relief to many cases; and a little lobelia with it makes an effective combination. Smoking the leaves in asthma is a common practice among the natives. Being itself largely stimulating, it may be combined with the relaxing glycyrrhiza, especially when it is necessary to allay the vexatious tickling in the throat that accom- panies many coughs. In cases of phthisis, the yerba santa alone is good for throat tickling; but beyond its influence as a reliable balsamic expectorant, it is not to be depended on in that malady. For chronic coughs with weakness of the respiratory mucous membranes and profuse expectoration, its stimulating and mildly tonic properties make it an admirable article, especially if aided by the antispasmodic and astringent properties of either of the viburnums of hamamelis, or of trillium. In aphonia, and the half-paralyzed condition of the laryngeal muscles of some coughs, it is excellent, alone or with such a stimulant as xanthoxylum. The action of yerba santa on the renal organs deserves more attention than it has received, especially in chronic cystitis and gleet. It makes a fair stimulating addendum to such diuretics as eupatorium purpureum and juniper berries; and to such uterine agents as mitchella and polygonatum for lax conditions of the female organs. Dose of the fluid extract, 5 to 30 drops or more every four or three hours. Its resinous character prevents its being miscible with water; but when a little alkali is added it is more miscible and makes a clear mixture with syrups. Combined with coriander, cinnamon and other aromatics it is used to disguise the bitterness of quinine. It is not compatible with acids.

Botanical Information

Botanical Description (E. angustifolium):

This perennial shrub grows up to 2 m tall. Young stems are glabrous and sticky with resin; older stems have shredding bark. The dark green, resinous, sticky leaves are lanceolate to narrow-linear with toothed, rolled-under margins from 3–10 cm long. The undersides are white and tomentose (the upper surfaces are glabrous). The inflorescences are scorpoid cymes in terminal clusters. The flowers have 5 white (sometimes lilac) petals fused into a tube 4–7 mm long and 5 green sepals fused and appearing as 5-lobed. All foliage exudes a pleasant odor. Fruits are ovoid, 4-valved capsules about 2 mm long. Flowering occurs from April to August.

Native Habit and Current Range (E. angustifolium):

This shrub grows on dry, rocky slopes in chaparral, from 600–2100 m altitude. (610-2134 m). It is found from California to Nevada and Utah, south to Arizona and Baja California. So far this species has not been spread outside its native range.

This perennial shrub grows up to 2 m tall. Young stems are glabrous and sticky with resin; older stems have shredding bark. The dark green, resinous, sticky leaves are lanceolate to narrow-linear with toothed, rolled-under margins from 3–10 cm long. The undersides are white and tomentose (the upper surfaces are glabrous). The inflorescences are scorpoid cymes in terminal clusters. The flowers have 5 white (sometimes lilac) petals fused into a tube 4–7 mm long and 5 green sepals fused and appearing as 5-lobed. All foliage exudes a pleasant odor. Fruits are ovoid, 4-valved capsules about 2 mm long. Flowering occurs from April to August.

Native Habit and Current Range (E. angustifolium):

This shrub grows on dry, rocky slopes in chaparral, from 600–2100 m altitude. (610-2134 m). It is found from California to Nevada and Utah, south to Arizona and Baja California. So far this species has not been spread outside its native range.

Harvesting, Cultivation, and Ecology

Cultivation: If any species of this are in cultivation, it is on a very small scale and mostly for the horticultural trade in the SW USA. It has been recommended to sow the seed of E. californicum in the greenhouse in the spring, the prick out seedlings into large individual pots and keep them in the greenhouse through their first winter, finally transplanting in late spring/early summer of their second year (Huxley 1992). Protect the young plants from cold the first two winters outdoors, ideally by planting next to rocks or a stone wall to radiate more heat. Plant in full sun. It prefers very well-drained, sandy soil and can tolerate clay and serpentine soils and doesn't mind if the soil is disturbed. Prune sparingly and only in late spring or early summer; do not prune back to the stem until it is older than 2 years.

Wildcrafting: This is the source of most commercial yerba santa. Since only leaves are taken, it does little harm to harvest (sparingly) from these plants. Some new growth should be left on each plant harvested. Only relatively well established and substantial stands should be harvested for greatest certainty of survival of the species.

Ecology: This is not a hugely popular in herbal medicine, and thus there is relatively little harvesting pressure. There is some habitat loss and the global climate emergency seems to be adversely affecting many populations. It is normally fire hardy, but the extreme wildfires human activity have created will kill it. Overall it is not clear what the exact ecological status is of each species. However, they have become more difficult to obtain in commerce lately suggesting there may be mounting problems (this may also reflect declining demand for the plant and thus reduced interest among growers or wildcrafters in supplying it, as well as the aging problem that is severely reducing the number of wildcrafters).

Wildcrafting: This is the source of most commercial yerba santa. Since only leaves are taken, it does little harm to harvest (sparingly) from these plants. Some new growth should be left on each plant harvested. Only relatively well established and substantial stands should be harvested for greatest certainty of survival of the species.

Ecology: This is not a hugely popular in herbal medicine, and thus there is relatively little harvesting pressure. There is some habitat loss and the global climate emergency seems to be adversely affecting many populations. It is normally fire hardy, but the extreme wildfires human activity have created will kill it. Overall it is not clear what the exact ecological status is of each species. However, they have become more difficult to obtain in commerce lately suggesting there may be mounting problems (this may also reflect declining demand for the plant and thus reduced interest among growers or wildcrafters in supplying it, as well as the aging problem that is severely reducing the number of wildcrafters).

References

Reynolds GW, Proksch P, Rodriguez E (1985) "Prenylated phenolics that cause contact dermatitis from glandular trichomes of Turricula parryi" Planta Med 51(6):494–8.

Adams JD, Garcia C (2005) "Palliative care among Chumash people" Evid Based Complemen Altern Med 2(2):143–7.

Barrows DP (1967) The Ethno-Botany of the Coahuilla Indians of Southern California (Banning CA. Malki Museum Press. Originally Published 1900).

Bocek BR (1984) "Ethnobotany of Costanoan Indians, California, Based on Collections by John P. Harrington" Economic Botany 38(2):240–55.

Cook WH (1896) A Compend of the New Materia Medica Together With Additional Descriptions of Some Old Remedies (Chicago: Self-published).

Crouthamel SJ (2009) Luiseño ethnobotany. https://www2.palomar.edu/users/scrouthamel/luisenob.htm [accessed 16 Jan 2022].

Dentali SJ, Hoffmann JJ (1992) "Potential antiinfective agents from Eriodictyon angustifolium and Salvia apiana" Int J Pharmacog 30:223.

Felter HW (1922) Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, reprinted 1998).

Fletcher JN, Kinghorn AD, Slack JP, et al. (2011) "In vitro evaluation of flavonoids from Eriodictyon californicum for antagonist activity against the bitterness receptor hTAS2R31" J Agric Food Chem 59(24):13117–21.

Garth TR (1953) "Atsugewi Ethnography" Anthropological Records 14(2):140–1.

Hasegawa E, Nakagawa S, Sato M, et al. (2013) "Effect of polyphenols on production of steroid hormones from human adrenocortical NCI-H295R cells" Biol Pharm Bull 36(2):228–37.

Hickman JC (ed) The Jepson Manual (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Huxley A (1992) The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening (Macmillan Press).

Lee E, Jeong KW, Shin A, et al. (2013) "Binding model for eriodictyol to Jun-N terminal kinase and its anti-inflammatory signaling pathway" BMB Rep 46(12):594–9.

Lewin L (1894) "Über die Geschmacksverbesserung von Medicamenten und über Saturationen" Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift 28:644–5.

Ley JP, Krammer G, Reinders G, Gatfield IL, Bertram HJ (2005) "Evaluation of bitter masking flavanones from herba [sic] santa (Eriodictyon californicum (H and A) Torr, Hydrophyllaceae)" J Agric Food Chem 53(15):6061–6.

Liu YL, et al. (1992) "Isolation of potential cancer chemopreventive agents from Eriodictyon californicum" J Nat Prod 55:357–63.

Moore M (2003a) "Eriodictyon, Yerba Santa" Southwest School of Botanical Medicine Plant Folio, http://www.swsbm.com/homepage/

Moore M (2003b) Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West Revised and Expanded (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press).

Park SJ, Lee YH, Lee KH, Kim TJ (2013) "Effect of eriodictyol on the development of atopic dermatitis-like lesions in ICR mice" Biol Pharm Bull 36(8):1375–9.

Reichelt KV, Peter R, Paetz S, et al. (2010) "Characterization of flavor modulating effects in complex mixtures via high temperature liquid chromatography" J Agric Food Chem 58(1):458–64.

Rother R (1887) "Some constituents of yerba santa" Am J Pharm 59(5) (\url{http://www.henriettesherbal.com/eclectic/journals/ajp1887/05-yerba-santa.html).

Salle AJ, Jann GJ, Wayne LG (1951) "Studies on the antibacterial properties of Eriodictyon californicum" Arch Biochem Biophys 32(1):121–3.

Straub I, Krügel U, Mohr F, et al. (2013) "Flavanones that selectively inhibit TRPM3 attenuate thermal nociception in vivo" Mol Pharmacol 84(5):736–50.

Taguchi N, Hata T, Kamiya E, et al. (2020) "Eriodictyon angustifolium extract, but not Eriodictyon californicum extract, reduces human hair greying" Int J Cosmet Sci 42(4):336–45.

Train P, Henrichs JR, Archer WA (1941) Medicinal Uses of Plants by Indian Tribes of Nevada (Washington DC. U.S. Department of Agriculture).

Ward JE, Munch JC (1930) J Am Pharm Assoc 19:1057.

Watahomigie LJ (1982) Hualapai Ethnobotany (Peach Springs, AZ. Hualapai Bilingual Program, Peach Springs School District #8).

Yoo JM, Kim JH, Park SJ, et al. (2012) "Inhibitory effect of eriodictyol on IgE/Ag-induced type I hypersensitivity" Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76(7):1285–90.

Adams JD, Garcia C (2005) "Palliative care among Chumash people" Evid Based Complemen Altern Med 2(2):143–7.

Barrows DP (1967) The Ethno-Botany of the Coahuilla Indians of Southern California (Banning CA. Malki Museum Press. Originally Published 1900).

Bocek BR (1984) "Ethnobotany of Costanoan Indians, California, Based on Collections by John P. Harrington" Economic Botany 38(2):240–55.

Cook WH (1896) A Compend of the New Materia Medica Together With Additional Descriptions of Some Old Remedies (Chicago: Self-published).

Crouthamel SJ (2009) Luiseño ethnobotany. https://www2.palomar.edu/users/scrouthamel/luisenob.htm [accessed 16 Jan 2022].

Dentali SJ, Hoffmann JJ (1992) "Potential antiinfective agents from Eriodictyon angustifolium and Salvia apiana" Int J Pharmacog 30:223.

Felter HW (1922) Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, reprinted 1998).

Fletcher JN, Kinghorn AD, Slack JP, et al. (2011) "In vitro evaluation of flavonoids from Eriodictyon californicum for antagonist activity against the bitterness receptor hTAS2R31" J Agric Food Chem 59(24):13117–21.

Garth TR (1953) "Atsugewi Ethnography" Anthropological Records 14(2):140–1.

Hasegawa E, Nakagawa S, Sato M, et al. (2013) "Effect of polyphenols on production of steroid hormones from human adrenocortical NCI-H295R cells" Biol Pharm Bull 36(2):228–37.

Hickman JC (ed) The Jepson Manual (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Huxley A (1992) The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening (Macmillan Press).

Lee E, Jeong KW, Shin A, et al. (2013) "Binding model for eriodictyol to Jun-N terminal kinase and its anti-inflammatory signaling pathway" BMB Rep 46(12):594–9.

Lewin L (1894) "Über die Geschmacksverbesserung von Medicamenten und über Saturationen" Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift 28:644–5.

Ley JP, Krammer G, Reinders G, Gatfield IL, Bertram HJ (2005) "Evaluation of bitter masking flavanones from herba [sic] santa (Eriodictyon californicum (H and A) Torr, Hydrophyllaceae)" J Agric Food Chem 53(15):6061–6.

Liu YL, et al. (1992) "Isolation of potential cancer chemopreventive agents from Eriodictyon californicum" J Nat Prod 55:357–63.

Moore M (2003a) "Eriodictyon, Yerba Santa" Southwest School of Botanical Medicine Plant Folio, http://www.swsbm.com/homepage/

Moore M (2003b) Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West Revised and Expanded (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press).

Park SJ, Lee YH, Lee KH, Kim TJ (2013) "Effect of eriodictyol on the development of atopic dermatitis-like lesions in ICR mice" Biol Pharm Bull 36(8):1375–9.

Reichelt KV, Peter R, Paetz S, et al. (2010) "Characterization of flavor modulating effects in complex mixtures via high temperature liquid chromatography" J Agric Food Chem 58(1):458–64.

Rother R (1887) "Some constituents of yerba santa" Am J Pharm 59(5) (\url{http://www.henriettesherbal.com/eclectic/journals/ajp1887/05-yerba-santa.html).

Salle AJ, Jann GJ, Wayne LG (1951) "Studies on the antibacterial properties of Eriodictyon californicum" Arch Biochem Biophys 32(1):121–3.

Straub I, Krügel U, Mohr F, et al. (2013) "Flavanones that selectively inhibit TRPM3 attenuate thermal nociception in vivo" Mol Pharmacol 84(5):736–50.

Taguchi N, Hata T, Kamiya E, et al. (2020) "Eriodictyon angustifolium extract, but not Eriodictyon californicum extract, reduces human hair greying" Int J Cosmet Sci 42(4):336–45.

Train P, Henrichs JR, Archer WA (1941) Medicinal Uses of Plants by Indian Tribes of Nevada (Washington DC. U.S. Department of Agriculture).

Ward JE, Munch JC (1930) J Am Pharm Assoc 19:1057.

Watahomigie LJ (1982) Hualapai Ethnobotany (Peach Springs, AZ. Hualapai Bilingual Program, Peach Springs School District #8).

Yoo JM, Kim JH, Park SJ, et al. (2012) "Inhibitory effect of eriodictyol on IgE/Ag-induced type I hypersensitivity" Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76(7):1285–90.