by Eric Yarnell, ND, RH(AHG)

Last updated 26 Jan 2022

This monograph is protected by copyright and is intended only for use by health care professionals and students. You may link to this page if you are sharing it with others in health care, but may not otherwise copy, alter, or share this material in any way. By accessing this material you agree to hold the author harmless for any use of this information.Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site. Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site.

Table of Contents

Clinical Highlights

Juniper pistillate cone (often mislabeled "berry") is a potent antimicrobial, diuretic, and inflammation modulator.

Juniper is most important for treating urinary and respiratory tract infections.

Juniper is generally safe, with an undeserved reputation for causing kidney harm. Juniper should be avoided in pregnancy.

Juniper is most important for treating urinary and respiratory tract infections.

Juniper is generally safe, with an undeserved reputation for causing kidney harm. Juniper should be avoided in pregnancy.

Clinical Fundamentals

Part Used: the pistillate (female or seed) cone (or strobilus). This is often mislabeled a "berry." As this is a gymnosperm, it cannot have a true berry as a fruit, because berries form from ovarian tissue which is lacking in gymnosperms. The cone is actually made up of flesh scales that have merged together to give a berry-like appearance. Any further talk of "juniper berries" will only demonstrate your ignorance of the natural world.

Taste: pungent, spicy, very strong, characteristic juniper flavor

Major Actions:

Older studies clearly document that juniper is aquaretic, meaning it increases urine volume by increasing glomerular filtration rate, probably by dilating preglomerular arterioles and thereby increasing the amount of blood filtered (Janku, et al. 1960; Janku, et al. 1957). However, the exact mechanisms of its actions have not been determined and it could be a diuretic (that is, changing renal handling of electrolytes thus causing increased urine production).

A 10% infusion, 0.1% volatile oil, and 0.01% terpinen-4-ol extracted from juniper all showed significant aquaretic effects in rats (Stanic, et al. 1998). This highlights that non-terpenoid components in the plant are also potentially aquaretic and/or diuretic. On the other hand, one study found that lyophilized aqueous extracts (25 mg/kg body weight) were not diuretic in rats, though they were mildly antihypertensive and analgesic (Lasheras, et al. 1986). Another study found that juniper seed cone infusion doubled chloride output in the urine of rats, supporting a diuretic effect of the herb (Volmor and Giebel 1938).

Major Organ System Affinities

Major Indications:

The idea that juniper is harmful for people with kidney infections is a myth, and deprives many patients with pyelonephritis of this useful and important herb.

A German clinical trial has demonstrated that bathing with volatile oils of juniper and Gaultheria procumbens (wintergreen) increased peripheral blood circulation and reduced pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Uehleke 1996).

Major Constituents:

Juniper branches contain a large amount of calcium. The Diné (Navajo) would traditionally burn the branches to ash and add this to corn meal to improve its digestibility. Modern analysis found 280--300 mg calcium/g of ash (Begay 2017).

Adverse Effects: Two famed aromatherapists have been unable to find any source which showed Juniperus communis volatile oil to be abortificient or contraindicated in kidney disease (Tisserand and Balacs 1995). They believe confusion of J. sabina (savin) and juniper is to blame for this historical, but apparently inaccurate, bad reputation. Savin has been shown to cause uterine contractions (Renaux and La Barre 1941). Tisserand and Balacs' view is buttressed by research showing that when rats were given enormous doses of juniper volatile oil (up to 1 g/kg) orally for 28 days, there was no negative impact on function or structure of the kidneys or any other body systems (Schilcher and Leuschner 1997). It has further been proposed that occasional reports of kidney problems may be due to use of oils that have a high pinene/terpinene-4-ol ratio, suggesting that pinenes may be causing problems while terpinene-4-ol is safe and the major diuretic component of the oil (Schilcher, et al. 1993). See a further discussion elsewhere on this site.

Juniper pollen is a serious aeroallergen in areas where the tree is common (Sposato and Scalese 2013). Juniper of various species in this context is frequently called cedar but this is a confusing and inaccurate term.

Contraindications:

Drug Interactions: There are no known interactions with pharmaceuticals, including no known or suspected interactions with antibiotics or phenazopyridine.

Taste: pungent, spicy, very strong, characteristic juniper flavor

Major Actions:

- Antimicrobial

- Diuretic

- Inflammation modulating

- Counterirritant (topical)

Older studies clearly document that juniper is aquaretic, meaning it increases urine volume by increasing glomerular filtration rate, probably by dilating preglomerular arterioles and thereby increasing the amount of blood filtered (Janku, et al. 1960; Janku, et al. 1957). However, the exact mechanisms of its actions have not been determined and it could be a diuretic (that is, changing renal handling of electrolytes thus causing increased urine production).

A 10% infusion, 0.1% volatile oil, and 0.01% terpinen-4-ol extracted from juniper all showed significant aquaretic effects in rats (Stanic, et al. 1998). This highlights that non-terpenoid components in the plant are also potentially aquaretic and/or diuretic. On the other hand, one study found that lyophilized aqueous extracts (25 mg/kg body weight) were not diuretic in rats, though they were mildly antihypertensive and analgesic (Lasheras, et al. 1986). Another study found that juniper seed cone infusion doubled chloride output in the urine of rats, supporting a diuretic effect of the herb (Volmor and Giebel 1938).

Major Organ System Affinities

- Urinary Tract

- Respiratory Tract

Major Indications:

- Urinary tract infections, upper and lower, acute, chronic, or recurrent

- Respiratory infections, upper and lower

- Gastrointestinal infections

- Rheumatism (topical)

- Headache (topical)

The idea that juniper is harmful for people with kidney infections is a myth, and deprives many patients with pyelonephritis of this useful and important herb.

A German clinical trial has demonstrated that bathing with volatile oils of juniper and Gaultheria procumbens (wintergreen) increased peripheral blood circulation and reduced pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Uehleke 1996).

Major Constituents:

- Terpenoids (Aliev, et al. 2015)

- Lignans

Juniper branches contain a large amount of calcium. The Diné (Navajo) would traditionally burn the branches to ash and add this to corn meal to improve its digestibility. Modern analysis found 280--300 mg calcium/g of ash (Begay 2017).

Adverse Effects: Two famed aromatherapists have been unable to find any source which showed Juniperus communis volatile oil to be abortificient or contraindicated in kidney disease (Tisserand and Balacs 1995). They believe confusion of J. sabina (savin) and juniper is to blame for this historical, but apparently inaccurate, bad reputation. Savin has been shown to cause uterine contractions (Renaux and La Barre 1941). Tisserand and Balacs' view is buttressed by research showing that when rats were given enormous doses of juniper volatile oil (up to 1 g/kg) orally for 28 days, there was no negative impact on function or structure of the kidneys or any other body systems (Schilcher and Leuschner 1997). It has further been proposed that occasional reports of kidney problems may be due to use of oils that have a high pinene/terpinene-4-ol ratio, suggesting that pinenes may be causing problems while terpinene-4-ol is safe and the major diuretic component of the oil (Schilcher, et al. 1993). See a further discussion elsewhere on this site.

Juniper pollen is a serious aeroallergen in areas where the tree is common (Sposato and Scalese 2013). Juniper of various species in this context is frequently called cedar but this is a confusing and inaccurate term.

Contraindications:

- Long-term use internally of large doses (for more than 30 days consecutively).

- High doses in chronic renal disease.

- Known allergy to the herb.

- History of hematuria or proteinuria in response to taking juniper.

- Use for more than 3–4 days consecutively during pregnancy. Volatile oil should be avoided for oral use completely during pregnancy until more information is available.

- A review of safety of topical use of various juniper extracts found that there is insufficient data to support chronic topical use (Anonymous 2001).

- Volatile oil overdose can cause neurotoxicity, though there are also scattered reports of hematuria and other signs of kidney damage. Overdose of other preparations may cause nausea, vomiting, and kidney damage.

Drug Interactions: There are no known interactions with pharmaceuticals, including no known or suspected interactions with antibiotics or phenazopyridine.

Pharmacy Essentials

Tincture: 1:3–1:5 w:v ratio, 50–60% ethanol

Dose:

Acute, adult: 0.5–1 ml q2–3h, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, for no more than three days

Chronic, adult: 0.5–1 ml tid (less often used chronically)

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Glycerite: not recommended (compounds in juniper do not extract well into glycerite)

Decoction: 2–3 g (1 tbsp) crushed pistillate cones simmered, covered, in 250 ml of water for 15 min, the result of which makes one cup (not 8 oz, but one dose). The amount of water used can be adjusted to patient taste in subsequent cups.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup q2–3h, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, for no more than three days

Chronic, adult: 1 cup tid (less often used chronically)

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Crude pistillate cones: 2–3 eaten q2–3h for no more than three days for acute infections.

Capsules:

Dose:

Acute, adult: 1 g q2–3h for no more than three days.

Chronic, adult: 1 g tid (less often taken chronically)

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Volatile oil, steam-distilled: Topically the smallest amount necessary to cover the affected region is utilized. Do not apply to large areas of broken skin due to the risk of excessive systemic absorption. Use only oils that have been tested and found to contain no more than a 3:1 ratio of hydrocarbon terpenes to terpene alcohols (particularly α-pinene:terpinene-4-ol) (Schilcher, et al. 1989). Unfortunately most products available in the world are not tested or labeled regarding their terpenoid composition. The acute internal adult dose is 1–3 gtt q2–3h internally, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, for no more than 48 h. It is not for use chronically or internally in children except under extraordinary conditions.

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Dose:

Acute, adult: 0.5–1 ml q2–3h, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, for no more than three days

Chronic, adult: 0.5–1 ml tid (less often used chronically)

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Glycerite: not recommended (compounds in juniper do not extract well into glycerite)

Decoction: 2–3 g (1 tbsp) crushed pistillate cones simmered, covered, in 250 ml of water for 15 min, the result of which makes one cup (not 8 oz, but one dose). The amount of water used can be adjusted to patient taste in subsequent cups.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup q2–3h, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, for no more than three days

Chronic, adult: 1 cup tid (less often used chronically)

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Crude pistillate cones: 2–3 eaten q2–3h for no more than three days for acute infections.

Capsules:

Dose:

Acute, adult: 1 g q2–3h for no more than three days.

Chronic, adult: 1 g tid (less often taken chronically)

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Volatile oil, steam-distilled: Topically the smallest amount necessary to cover the affected region is utilized. Do not apply to large areas of broken skin due to the risk of excessive systemic absorption. Use only oils that have been tested and found to contain no more than a 3:1 ratio of hydrocarbon terpenes to terpene alcohols (particularly α-pinene:terpinene-4-ol) (Schilcher, et al. 1989). Unfortunately most products available in the world are not tested or labeled regarding their terpenoid composition. The acute internal adult dose is 1–3 gtt q2–3h internally, adjusted for body size and sensitivities, for no more than 48 h. It is not for use chronically or internally in children except under extraordinary conditions.

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Other Names

Latin synonyms:

Current correct Latin binomial: Juniperus communis L

Juniperus argaea Bal ex Parl

uniperus borealis Salisb

Juniperus caucasica Fisch ex Gordon

Juniperus oblonga-pendula (Loudon) Van Geert ex K Koch

Juniperus oxycedrus ssp hemisphaerica (Presl) Emil Schmid ex Atzei & V Picci

Juniperus taurica Lindl & Gordon

Juniperus vulgaris Bubani

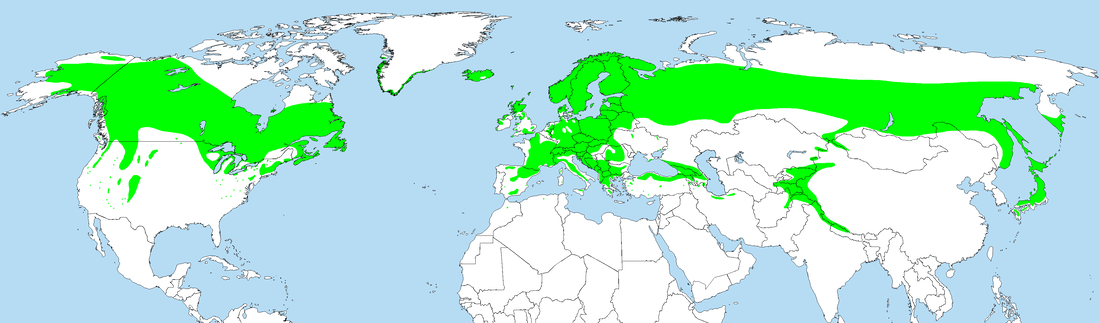

Given the incredibly widespread distribution of common juniper and related species around the northern hemisphere, almost every language there has a name for juniper, some of which are cataloged below. Note that the Swiss city of Geneva is an anglicization of the French word for juniper (genévrier), and gin is ultimately derived from the Dutch word for juniper (genever).

English Common Names: juniper, common juniper, Siberian juniper, dwarf juniper, ground juniper

Native American Common Names (grouped linguistically and geographically):

Iñupiaq (Alaskan Inuit, Eskimo-Aleut) Common Name: tulukkam asriaḳ (seed cone, “raven’s berry”)

Atnakenaege' (Ahtna, Athabascan) Common Names: dzeł gige' ("mountain berry"), saghani gige' ("raven's berries")

Witsuwit’en (Northern Carrier, Athabascan) Common Name: detsan (J. scopulorum)

Diné bizaad (Navajo, Athabascan) Common Names:

J. communis tree: gad, kat

J. scopulorum tree: gad ni'eetlii

Juniper seed cone: dzidze'

Plains Apache (Athabascan) Common Names: gyad, diłkałéé ("odor spilling out"); gyadschích'itł'ee ("kinky cedar"), gyadíshjịdée ("stunted cedar", for J. pinchotii)

O'otham (Northern Tepehuán, Athabascan) Common Names: gáyi, gágayi

halq̓eméylem (Halkomelem, Upriver dialect, Salish) Common Name: th’el’á:tel

SENĆOŦEN (Northern Straits Salish dialect, Salish) Common Name: p̓ət̓thəngi-iłč, pəpət̓thíng (“skunky/rank-smelling tree,” for J. maritima)

dxʷləšúcid (Lushootseed, Salish) Common Name: i'yalats ("smells strong", for J. scopulorum)

ńseĺxčiń (Colville-Okanagan, Salish) Common Name: puńłp

Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe/Chippewa, Algonquian) Common Name: gagawan dagisid, miskawa'wak ("red wood")

Lenape (Delaware, Algonquian) Common Name: mehokhócus

Sawanwa (Shawnee, Algonquian) Common Name: sequaw ("red")

Cáuijògà (Kiowa, Tanoan) Common Names: 'ko-kee-äd-la, a-heeñ, ya-'toñ-ba

Chahta' (Choctaw, Muskogean) Common Names: chuala, chuatla

Chikashshanompa' (Chickasaw, Muskogean) Common Namse: chow a ala', chow a hla', chawala

Hitchiti-Mikasuki (Muskogean) Common Names: acinî, vcénv, a'tsina' (J. virginiana)

Dakhótiyapi (Dakota, Siouan) Common Names: hante ("eggs"), ḥante sha ("red eggs"), sha ("red"), ḥante itika ("cedar eggs", referring to the seed cones)

Katapa (Catawba, Siouan) Common Name: atcuwe se'ʔ, se wyhukse’, aswetci’here, icuwése

Pánka iyé (Ponca, Siouan) Common Name: maazi

Wazhazhe ie (Osage, Siouan) Common Name: xon-dse hi ("red tree")

Onǫda’gegá’ (Onondaga, Iriquoian) Common Name: noehntotakri

Tsalagi Gawonihisdi (Cherokee, Iriquoian) Common Name: a'-tsi-na' or atsina ᎠᏥᎾ

Neme taikwappeh (Shoshone, Uto-Aztecan) Common Names:

J. communis: añ'-go-gwa-nûp, mah-hav-wa;

J. osteosperma: sahn-a-poh

J. monosperma: sah-mah-be, sah'-nah-be, sahm-wah'-be

J. scopulorum: bah-sah-mabe

J. occidentalis: sam-ah-bee

Juniper or cedar in general: sama-pi-tta, sama-pin, samapi, sawabi, sawavi, tse'-kev-ve, wa'-pi, waa"-pi-tta

Juniper seed cones in general: eshap'pu, ishap'pu, sanappoo, sanappoo-a

Numu (Paiute, Uto-Aztecan) Common Name: wapi

Nʉmʉ Tekwapʉ (Comanche, Uto-Aztecan) Common Name: ekawai:pv

Rarámuri ra'ícha (Tarahumara, Uto-Aztecan) Common Names: aborí, aorí, ahualí, awerí, kawarí, koarí, wakarí, awarí, gayorí, oyorí, orwí, péchuri (J. pachyphlaea, J. deppeana, and J. durangensis)

Pâri Pakûru' (Pawnee, Caddoan) Common Name: tawatsaako

X̱aat Kíl (Haida, isolate) Common Name: hlḵ'ám.aal (also general term for evergreen bough), hlḵ'ám.aal gin gyáa'alaas, hlḵ'ám.aal ginn gyaa.alaas ("muskeg evergreen thing"), ḵ'ál.aa hlḵ'ámalaay, ḵ'ál.aa hlḵ'ám.alee, ḵ'álaa ts'aláa (whole tree); ǥáay'angwaal, ǥaayangʔwaal (seed cones)

wá:šiw ʔítlu (Washo, isolate) Common Name: paai

Ishak-koi (Atakapa, isolate) Common Names: khicuc, khishoush

Albanian Common Names: dëllinja

Arabic Common Names: earear shayie العربية, alearear shajar العرعر شجر

Basque Common Names: ipar-ipuru, ipuruak

Bengali Common Name: havusha

Bosnian Common Name: smreka

Catalan Common Names: ginebra, ginebre comú

Danish Common Names: enebær, almindelig Ene

Deccan Common Name: abhal

Dutch Common Names: genever boom, jeneverbes

Esperanto Common Name: ordinara junipero

Estonian Common Name: harilik kadakas

Finnish Common Name: kataja

French Common Names: genévrier commun, genévrier, genévrier nain

German Common Names: Wacholder, Wacholderbeeren, Gemeine Wacholder, Gemeiner Wacholder

Greek (Modern) Common Name: arkevthos Άρκευθος

Hindi Common Names: aaraar, haubera, abhal

Hungarian Common Name: boróka, közönséges boróka

Icelandic Common Name: einir

Irish Common Names: aiteal (tree), caor aitil (seed cone)

Italian Common Names: ginepro, ginepro comune

Japanese Common Names: seiyounezu セイヨウネズ, junipā ジュニパー

Kashmiri Common Names: betar, petthri, pama, chui, haubler

Lithuanian Common Name: paprastasis kadagys

Mandarin Chinese Common Name: cì bǎi 刺柏 ("thorn cedar/cypress")

Marathi Common Names: hosha

Norwegian Common Name: einer

Persian Common Name: bab-ul-bruta

Polish Common Name: jałowiec pospolity

Portuguese Common Names: zimbro, junípero-comum

Punjabi Common Name: abhal

Romanian Common Names: jenuper, ienupăr

Russian Common Name: mozhzhevel'nik (можжевельник), pojjevelnik, Можжевельник обыкновенный (mozhzhevel'nik obyknovennyy)

Sami (Davvisámegiella) Common Name: reatká

Sanskrit Common Name: hapuṣā हपुषा

Scottish Gaelic Common Names: iubhar-beinne, iubhar-creige, iubhar-talmhainn; aiteann, staoin ("crooked", this is also used to mean "tin, "pewter," "shallow," Glechoma hederacea), caora-staoin ("juniper cone"), sineabhar, beacora-leacra, bior-leacainn, aiteann-coitcheann, lus na staoine

Serbo-Croatian Common Names: obična borovica, kleka

Spanish Common Names: enebro, ginepro nano (Spain); sabina colorado ("red cedar"), savin (New Mexico); tázcate, enebro, cedro, sabina, tuya, grojo, junípero, cada, ciprés, tázcate sabino, sabino, sabino colorado (Mexico)

Swedish Common Name: en

Turkish Common Name: adi ardıç

Walloon Common Name: franc pectî

Welsh Common Name: merywen

Current correct Latin binomial: Juniperus communis L

Juniperus argaea Bal ex Parl

uniperus borealis Salisb

Juniperus caucasica Fisch ex Gordon

Juniperus oblonga-pendula (Loudon) Van Geert ex K Koch

Juniperus oxycedrus ssp hemisphaerica (Presl) Emil Schmid ex Atzei & V Picci

Juniperus taurica Lindl & Gordon

Juniperus vulgaris Bubani

Given the incredibly widespread distribution of common juniper and related species around the northern hemisphere, almost every language there has a name for juniper, some of which are cataloged below. Note that the Swiss city of Geneva is an anglicization of the French word for juniper (genévrier), and gin is ultimately derived from the Dutch word for juniper (genever).

English Common Names: juniper, common juniper, Siberian juniper, dwarf juniper, ground juniper

Native American Common Names (grouped linguistically and geographically):

Iñupiaq (Alaskan Inuit, Eskimo-Aleut) Common Name: tulukkam asriaḳ (seed cone, “raven’s berry”)

Atnakenaege' (Ahtna, Athabascan) Common Names: dzeł gige' ("mountain berry"), saghani gige' ("raven's berries")

Witsuwit’en (Northern Carrier, Athabascan) Common Name: detsan (J. scopulorum)

Diné bizaad (Navajo, Athabascan) Common Names:

J. communis tree: gad, kat

J. scopulorum tree: gad ni'eetlii

Juniper seed cone: dzidze'

Plains Apache (Athabascan) Common Names: gyad, diłkałéé ("odor spilling out"); gyadschích'itł'ee ("kinky cedar"), gyadíshjịdée ("stunted cedar", for J. pinchotii)

O'otham (Northern Tepehuán, Athabascan) Common Names: gáyi, gágayi

halq̓eméylem (Halkomelem, Upriver dialect, Salish) Common Name: th’el’á:tel

SENĆOŦEN (Northern Straits Salish dialect, Salish) Common Name: p̓ət̓thəngi-iłč, pəpət̓thíng (“skunky/rank-smelling tree,” for J. maritima)

dxʷləšúcid (Lushootseed, Salish) Common Name: i'yalats ("smells strong", for J. scopulorum)

ńseĺxčiń (Colville-Okanagan, Salish) Common Name: puńłp

Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe/Chippewa, Algonquian) Common Name: gagawan dagisid, miskawa'wak ("red wood")

Lenape (Delaware, Algonquian) Common Name: mehokhócus

Sawanwa (Shawnee, Algonquian) Common Name: sequaw ("red")

Cáuijògà (Kiowa, Tanoan) Common Names: 'ko-kee-äd-la, a-heeñ, ya-'toñ-ba

Chahta' (Choctaw, Muskogean) Common Names: chuala, chuatla

Chikashshanompa' (Chickasaw, Muskogean) Common Namse: chow a ala', chow a hla', chawala

Hitchiti-Mikasuki (Muskogean) Common Names: acinî, vcénv, a'tsina' (J. virginiana)

Dakhótiyapi (Dakota, Siouan) Common Names: hante ("eggs"), ḥante sha ("red eggs"), sha ("red"), ḥante itika ("cedar eggs", referring to the seed cones)

Katapa (Catawba, Siouan) Common Name: atcuwe se'ʔ, se wyhukse’, aswetci’here, icuwése

Pánka iyé (Ponca, Siouan) Common Name: maazi

Wazhazhe ie (Osage, Siouan) Common Name: xon-dse hi ("red tree")

Onǫda’gegá’ (Onondaga, Iriquoian) Common Name: noehntotakri

Tsalagi Gawonihisdi (Cherokee, Iriquoian) Common Name: a'-tsi-na' or atsina ᎠᏥᎾ

Neme taikwappeh (Shoshone, Uto-Aztecan) Common Names:

J. communis: añ'-go-gwa-nûp, mah-hav-wa;

J. osteosperma: sahn-a-poh

J. monosperma: sah-mah-be, sah'-nah-be, sahm-wah'-be

J. scopulorum: bah-sah-mabe

J. occidentalis: sam-ah-bee

Juniper or cedar in general: sama-pi-tta, sama-pin, samapi, sawabi, sawavi, tse'-kev-ve, wa'-pi, waa"-pi-tta

Juniper seed cones in general: eshap'pu, ishap'pu, sanappoo, sanappoo-a

Numu (Paiute, Uto-Aztecan) Common Name: wapi

Nʉmʉ Tekwapʉ (Comanche, Uto-Aztecan) Common Name: ekawai:pv

Rarámuri ra'ícha (Tarahumara, Uto-Aztecan) Common Names: aborí, aorí, ahualí, awerí, kawarí, koarí, wakarí, awarí, gayorí, oyorí, orwí, péchuri (J. pachyphlaea, J. deppeana, and J. durangensis)

Pâri Pakûru' (Pawnee, Caddoan) Common Name: tawatsaako

X̱aat Kíl (Haida, isolate) Common Name: hlḵ'ám.aal (also general term for evergreen bough), hlḵ'ám.aal gin gyáa'alaas, hlḵ'ám.aal ginn gyaa.alaas ("muskeg evergreen thing"), ḵ'ál.aa hlḵ'ámalaay, ḵ'ál.aa hlḵ'ám.alee, ḵ'álaa ts'aláa (whole tree); ǥáay'angwaal, ǥaayangʔwaal (seed cones)

wá:šiw ʔítlu (Washo, isolate) Common Name: paai

Ishak-koi (Atakapa, isolate) Common Names: khicuc, khishoush

Albanian Common Names: dëllinja

Arabic Common Names: earear shayie العربية, alearear shajar العرعر شجر

Basque Common Names: ipar-ipuru, ipuruak

Bengali Common Name: havusha

Bosnian Common Name: smreka

Catalan Common Names: ginebra, ginebre comú

Danish Common Names: enebær, almindelig Ene

Deccan Common Name: abhal

Dutch Common Names: genever boom, jeneverbes

Esperanto Common Name: ordinara junipero

Estonian Common Name: harilik kadakas

Finnish Common Name: kataja

French Common Names: genévrier commun, genévrier, genévrier nain

German Common Names: Wacholder, Wacholderbeeren, Gemeine Wacholder, Gemeiner Wacholder

Greek (Modern) Common Name: arkevthos Άρκευθος

Hindi Common Names: aaraar, haubera, abhal

Hungarian Common Name: boróka, közönséges boróka

Icelandic Common Name: einir

Irish Common Names: aiteal (tree), caor aitil (seed cone)

Italian Common Names: ginepro, ginepro comune

Japanese Common Names: seiyounezu セイヨウネズ, junipā ジュニパー

Kashmiri Common Names: betar, petthri, pama, chui, haubler

Lithuanian Common Name: paprastasis kadagys

Mandarin Chinese Common Name: cì bǎi 刺柏 ("thorn cedar/cypress")

Marathi Common Names: hosha

Norwegian Common Name: einer

Persian Common Name: bab-ul-bruta

Polish Common Name: jałowiec pospolity

Portuguese Common Names: zimbro, junípero-comum

Punjabi Common Name: abhal

Romanian Common Names: jenuper, ienupăr

Russian Common Name: mozhzhevel'nik (можжевельник), pojjevelnik, Можжевельник обыкновенный (mozhzhevel'nik obyknovennyy)

Sami (Davvisámegiella) Common Name: reatká

Sanskrit Common Name: hapuṣā हपुषा

Scottish Gaelic Common Names: iubhar-beinne, iubhar-creige, iubhar-talmhainn; aiteann, staoin ("crooked", this is also used to mean "tin, "pewter," "shallow," Glechoma hederacea), caora-staoin ("juniper cone"), sineabhar, beacora-leacra, bior-leacainn, aiteann-coitcheann, lus na staoine

Serbo-Croatian Common Names: obična borovica, kleka

Spanish Common Names: enebro, ginepro nano (Spain); sabina colorado ("red cedar"), savin (New Mexico); tázcate, enebro, cedro, sabina, tuya, grojo, junípero, cada, ciprés, tázcate sabino, sabino, sabino colorado (Mexico)

Swedish Common Name: en

Turkish Common Name: adi ardıç

Walloon Common Name: franc pectî

Welsh Common Name: merywen

Interchangeability of Species

There are numerous interchangeable species in this genus. They all have fleshy fruits (species with dry, mushy fruit with little aromatic flavor are not medicinal, such as J. deppeana (alligator juniper). Species utilized effectively by Dr. Yarnell or cited in expert literature as effective are discussed below.

J. californica (California juniper), found stretching along the central spine of California, a little bit of central western Arizona, and northern Baja California. Its fruits have a bluish cast.

J. coahuilensis (redberry juniper), found in the Sonoran desert, divided out of the genus formerly known as J. osteosperma (desert cedar), found in the same bioregion and also active. As its name suggests, it has smaller seed cones with a reddish cast.

J. monosperma (one-seed juniper), also found in the Sonoran desert and surrounding areas including the Great Basin, is great medicine.

J. osteosperma (Utah juniper), (formerly J. utahensis), is a medicinal species across the southwestern and central western USA.

J. oxycedrus (prickly juniper, cade), which yields volatile oil of cade, has been the subject of much research and is clearly quite antimicrobial.

J. sabina (savin) should be strictly avoided as it is much more toxic.

J. californica (California juniper), found stretching along the central spine of California, a little bit of central western Arizona, and northern Baja California. Its fruits have a bluish cast.

J. coahuilensis (redberry juniper), found in the Sonoran desert, divided out of the genus formerly known as J. osteosperma (desert cedar), found in the same bioregion and also active. As its name suggests, it has smaller seed cones with a reddish cast.

J. monosperma (one-seed juniper), also found in the Sonoran desert and surrounding areas including the Great Basin, is great medicine.

J. osteosperma (Utah juniper), (formerly J. utahensis), is a medicinal species across the southwestern and central western USA.

J. oxycedrus (prickly juniper, cade), which yields volatile oil of cade, has been the subject of much research and is clearly quite antimicrobial.

J. sabina (savin) should be strictly avoided as it is much more toxic.

Advanced Clinical Information

Additional Actions:

Additional Indications:

A group of 72 patients with Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, a very common skin infection due to o Leishmania major, L. tropica, L. aethiopica, or L. infantum, were all treated with cryotherapy, and then randomized (in a double-blind manner) to either apply a topical cream of Juniperus excelsa (Greek or Persian juniper) made from a 5% hydroethanol extract of the leaf or placebo cream three times daily for up to 12 weeks (Parvizi, et al. 2017). If lesions were progressing after 8 weeks patients were given oral antibiotics and treatment was considered a failure. In the end, 82% of the Persian juniper-treated group had total cure compared to just 34% of the placebo-treated group, a statistically significant difference favoring the herbal treatment. The time to resolution was significantly shorter and the number of cryotherapy treatments were significantly fewer (by almost half) in the Persian juniper compared to controls. Five patients had mild redness and flaking due to the Persian juniper cream, and only one of these stopped treatment because of it (but this patient did experience total cure of her lesions before stopping the cream).

Lambs fed a diet of 30% Juniperus pinchotii (redberry juniper) for one month had substantially less problems with Haemonchus contortus, the most common infectious nematode in ruminants, compared to those not fed redberry juniper, and had a much higher rate of clearance of the parasite when given ivermectin (Whitney, et al. 2013).

- Antineoplastic

- Butyrylcholinesterase (but not acetylcholinesterase) inhibiting (Orhan, et al. 2011)

- Corrigent (used to flavor gin in particular)

- Digestive stimulant, aromatic

- Hepatoprotective (Ved, et al. 2017; Singh, et al. 2016)

- Hypoglycemic

- Neuroprotective (Bais, et al. 2015)

Additional Indications:

- Atonic constipation

- Diabetes mellitus

- Dyspepsia

- Gastrointestinal infections

- Gout

- Hemorrhoids (topical paste of bark)

- Leishmaniasis, cutaneous (Parvizi, et al. 2017)

- Neuralgia (topically)

- Skin infections

- Wounds (topical paste of bark)

A group of 72 patients with Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, a very common skin infection due to o Leishmania major, L. tropica, L. aethiopica, or L. infantum, were all treated with cryotherapy, and then randomized (in a double-blind manner) to either apply a topical cream of Juniperus excelsa (Greek or Persian juniper) made from a 5% hydroethanol extract of the leaf or placebo cream three times daily for up to 12 weeks (Parvizi, et al. 2017). If lesions were progressing after 8 weeks patients were given oral antibiotics and treatment was considered a failure. In the end, 82% of the Persian juniper-treated group had total cure compared to just 34% of the placebo-treated group, a statistically significant difference favoring the herbal treatment. The time to resolution was significantly shorter and the number of cryotherapy treatments were significantly fewer (by almost half) in the Persian juniper compared to controls. Five patients had mild redness and flaking due to the Persian juniper cream, and only one of these stopped treatment because of it (but this patient did experience total cure of her lesions before stopping the cream).

Lambs fed a diet of 30% Juniperus pinchotii (redberry juniper) for one month had substantially less problems with Haemonchus contortus, the most common infectious nematode in ruminants, compared to those not fed redberry juniper, and had a much higher rate of clearance of the parasite when given ivermectin (Whitney, et al. 2013).

Classic Formulas

Newe (Shoshone) Cold Formula (Shemluck 1982)

Prepare an infusion of Artemisia tridentata (bah-guh-yoom, bah-hoe-be, big-leaf sagebrush) aerial parts (not just the leaves), throwing away the water then making a second infusion of the leaves (to avoid provoking emesis). During the second infusion, include twigs of J. osteosperma (sahn-a-poh, Utah juniper). Used for upper respiratory infections.

Dr. Yarnell's Urinary Tract Infection Fighter Formula

Arbutus menziesii (madrone) leaf tincture 30%

Solidago canadensis (goldenrod) aerial parts tincture 20%

Thymus vulgaris (thyme) aerial parts tincture 15%

Juniperus communis (juniper) seed cone tincture 15%

Fouquieria splendens (ocotillo) bark tincture 10%

Zingiber officinale (ginger) dry rhizome glycerite or tincture 5%

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) dry root glycerite or tincture 5%

Juniperus communis (juniper) seed cone steam-distilled volatile oil 5 drops/4 oz

Thymus vulgaris ct thymol (red thyme) aerial parts steam-distilled volatile oil 5 drops/4 oz

Sig: take 1 tsp q2h during for acute UTI. If symptoms are not dramatically better in 12–24 hours (if pyelonephritis is suspected, or for complicated UTI) or in 36–48 hours (for uncomplicated lower UTI), consider antibiotic therapy. If symptoms are waning after 48 hours then reduce dose to 1 tsp 4–5 times per day until symptoms are completely gone.

For pregnancy-related UTI, especially in the first trimester, substitute Salvia officinalis (garden sage) for the juniper and leave out the volatile oils.

Prepare an infusion of Artemisia tridentata (bah-guh-yoom, bah-hoe-be, big-leaf sagebrush) aerial parts (not just the leaves), throwing away the water then making a second infusion of the leaves (to avoid provoking emesis). During the second infusion, include twigs of J. osteosperma (sahn-a-poh, Utah juniper). Used for upper respiratory infections.

Dr. Yarnell's Urinary Tract Infection Fighter Formula

Arbutus menziesii (madrone) leaf tincture 30%

Solidago canadensis (goldenrod) aerial parts tincture 20%

Thymus vulgaris (thyme) aerial parts tincture 15%

Juniperus communis (juniper) seed cone tincture 15%

Fouquieria splendens (ocotillo) bark tincture 10%

Zingiber officinale (ginger) dry rhizome glycerite or tincture 5%

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) dry root glycerite or tincture 5%

Juniperus communis (juniper) seed cone steam-distilled volatile oil 5 drops/4 oz

Thymus vulgaris ct thymol (red thyme) aerial parts steam-distilled volatile oil 5 drops/4 oz

Sig: take 1 tsp q2h during for acute UTI. If symptoms are not dramatically better in 12–24 hours (if pyelonephritis is suspected, or for complicated UTI) or in 36–48 hours (for uncomplicated lower UTI), consider antibiotic therapy. If symptoms are waning after 48 hours then reduce dose to 1 tsp 4–5 times per day until symptoms are completely gone.

For pregnancy-related UTI, especially in the first trimester, substitute Salvia officinalis (garden sage) for the juniper and leave out the volatile oils.

Monograph from Eclectic Materia Medica (Felter 1922)

JUNIPERUS COMMUNIS.

The fruit (berries) [sic] of the Juniperus communis, Linné (Nat. Ord. Cupressaceae). An evergreen tree of Europe and America.

Common Names: Juniper, Juniper Berries [sic].

Principal Constituents.—A volatile oil (Oleum Juniperi) and an amorphous body, juniperin.

Preparations.—1. Infusum Juniperi, Infusion of Juniper (Berries [sic], 1 ounce; Boiling Water, 16 fluidounces; let stand one hour). Dose, 2 to 4 fluidounces. 2. Oleum Juniperi, Oil of Juniper. Colorless, faintly green or yellow oil of the juniper taste and odor. It should be kept protected from light in amber-hued bottles and in a cool place. Dose, 2 to 15 minims. 3. Spiritus Juniperi, Spirit of juniper (5 per cent oil). Dose, 5 to 60 minims. 4. Spiritus Juniperi Compositus, Compound Spirit of Juniper (Oils of juniper, Caraway, Fennel, Alcohol, and Water). Dose, 1 to 4 fluidrachms.

Specific Indications.—Renal atony with catarrhal and pus discharges; non-inflammatory irritability of the neck of the bladder.

Action and Therapy.—Juniper is a gastric stimulant and a stimulating diuretic to be used in atonic and depressed conditions, usually in chronic affections of the kidneys and urinary passages with catarrhal or pus-laden discharges. It is especially valuable in renal atony in the aged, with persistent sense of weight and dragging in the lumbar region. In uncomplicated renal hyperaemia or congestion, when the circulation is weak and no fever or inflammation is present, the careful use of juniper will relieve, and if albumen is present it may disappear under its use. It is often of great value in chronic nephritis, catarrh of the bladder, and chronic pyelitis to stimulate the sluggish epithelia and cause a freer flow of urine to wash away the unhealthy secretions. It is sometimes of value after scarlet fever or in the late stages when the kidneys are not yet inflamed, and after acute nephritis when the renal tone is diminished and secretion of urine is imperfect. Under no circumstances should it be used when there is active inflammation. The infusion is extremely useful in irritation of the bladder with recurrent attacks of distressing pain and frequent urination in women during the menopause and apparently due to taking cold. The infusion of juniper is the best preparation for most purposes. A pint may be taken in a day. When an alcoholic stimulant is needed in the abovenamed condition the spirit or compound spirit may be used. The oil is often efficient in non-inflammatory prostatorrhea and gleet. Juniper preparations are frequently exhibited in chronic structural diseases of the heart, liver, and kidneys, to stimulate the sound tissues to functionate and relieve the attendant dropsy. Usually they are combined with agents like citrate or acetate of potassium or with spirit of nitrous ether. In these conditions they must be used with judgment and caution. No preparation of juniper should be given in doses larger than recommended above, as suppression of urine, strangury, hematuria, or even uremic convulsions may result from its use.

The fruit (berries) [sic] of the Juniperus communis, Linné (Nat. Ord. Cupressaceae). An evergreen tree of Europe and America.

Common Names: Juniper, Juniper Berries [sic].

Principal Constituents.—A volatile oil (Oleum Juniperi) and an amorphous body, juniperin.

Preparations.—1. Infusum Juniperi, Infusion of Juniper (Berries [sic], 1 ounce; Boiling Water, 16 fluidounces; let stand one hour). Dose, 2 to 4 fluidounces. 2. Oleum Juniperi, Oil of Juniper. Colorless, faintly green or yellow oil of the juniper taste and odor. It should be kept protected from light in amber-hued bottles and in a cool place. Dose, 2 to 15 minims. 3. Spiritus Juniperi, Spirit of juniper (5 per cent oil). Dose, 5 to 60 minims. 4. Spiritus Juniperi Compositus, Compound Spirit of Juniper (Oils of juniper, Caraway, Fennel, Alcohol, and Water). Dose, 1 to 4 fluidrachms.

Specific Indications.—Renal atony with catarrhal and pus discharges; non-inflammatory irritability of the neck of the bladder.

Action and Therapy.—Juniper is a gastric stimulant and a stimulating diuretic to be used in atonic and depressed conditions, usually in chronic affections of the kidneys and urinary passages with catarrhal or pus-laden discharges. It is especially valuable in renal atony in the aged, with persistent sense of weight and dragging in the lumbar region. In uncomplicated renal hyperaemia or congestion, when the circulation is weak and no fever or inflammation is present, the careful use of juniper will relieve, and if albumen is present it may disappear under its use. It is often of great value in chronic nephritis, catarrh of the bladder, and chronic pyelitis to stimulate the sluggish epithelia and cause a freer flow of urine to wash away the unhealthy secretions. It is sometimes of value after scarlet fever or in the late stages when the kidneys are not yet inflamed, and after acute nephritis when the renal tone is diminished and secretion of urine is imperfect. Under no circumstances should it be used when there is active inflammation. The infusion is extremely useful in irritation of the bladder with recurrent attacks of distressing pain and frequent urination in women during the menopause and apparently due to taking cold. The infusion of juniper is the best preparation for most purposes. A pint may be taken in a day. When an alcoholic stimulant is needed in the abovenamed condition the spirit or compound spirit may be used. The oil is often efficient in non-inflammatory prostatorrhea and gleet. Juniper preparations are frequently exhibited in chronic structural diseases of the heart, liver, and kidneys, to stimulate the sound tissues to functionate and relieve the attendant dropsy. Usually they are combined with agents like citrate or acetate of potassium or with spirit of nitrous ether. In these conditions they must be used with judgment and caution. No preparation of juniper should be given in doses larger than recommended above, as suppression of urine, strangury, hematuria, or even uremic convulsions may result from its use.

Ethnobotanical Reports

Because the wood resists degradation by soil organisms, juniper was and is commonly used for fence posts and other building uses requiring close contact with soil.

It is generally considered a heating plant in traditional medical systems.

The Kalth Tindé or yát dìndé ("cedar/juniper people," Plains Apache) burned needles from J. pinchotii as incense during various rituals (Jordan 2008). This smoke was also commonly used around the home to ward off ghosts after the death of a family member, when thoughts of a dead relative could not be put aside, when a child was sick or crying inconsolably, or when an adult was sick or depressed. One informant suggested a decoction of leaves of juniper were used to stop bleeding after birth (echoing the use by some Rarámuri mentioned below), as well as to stop afterpains. The strong, rot-resistant wood of J. virginiana was prized for tipi poles, fence posts, drumsticks, skewers, staves, and flutes (heartwood). Obviously the connection with juniper was so close to these people they shared a name!

The Dzil Łigai Si'án Ndee (White Mountain Apache) reportedly used J. monosperma as an anticonvulsant, remedy for colds, flus, and coughs, and for unspecified female reproductive problems (Reagan 1929). They also ate the fruit as a food.

Juniper ash was mixed with Helenium hoopesii (sneezeweed) by the Diné to make a yellow dye (Shemluck 1982).

Ground stem of J. osteosperma was decocted together with stems of Tetradymia comosa (hairy horsebush) to treat upper respiratory tract infections by the Newe (Shoshone) (Shemluck 1982). Similarly the Paiute would combine young stems of J. osteosperma with the root of Wyethia mollis (wooly mule's ear') and decoct them for respiratory infections and fevers (Shemluck 1982). The Hopituh Shi-nu-mu (Hopi) made a tea of juniper and Artemisia filifolia (sand sagebrush) for indigestion (Shemluck 1982). The Diné (Navajo) would make a formula with Artemisia bigelovii (flat sagebrush), Artemisia carruthii (Carruth wormwood), Ceanothus fendleri (Fendler's red root), Tetradymia canescens (spineless horsebrush), Pinus spp (piñon pine), and juniper needles to protect from lightning, or possibly for extremely severe infections (Shemluck 1982). They also used spineless horsebrush leaf and juniper needles in a cold infusion for "ghost" infections, coughs, myalgias, indigestion, and respiratory infections (Shemluck 1982).

The Rarámuri (Tarahumara) say that a decoction of the needles and bark of J. pacyphlaea, J. deppeana or J. durangensis is emmenagogue and possibly abortifacient (Irigoyen-Rascón and Paredes 2015). A different community uses the same preparation to halt bleeding after delivery. Topical juniper needle poultice is used to treat impetigo. A decoction of needles is used internally for upper respiratory infections and coughs, and in a lotion for myalgia (direct topical application of tea also used this way), indigestion/stomach aches, respiratory infections, and pharyngitis. Juniper decoction was also used to protect fields from natural disasters (like hail) and to heal them from whatever ailments arose in the crops. Burning juniper boughs and exposing people, animals, and objects to the smoke to heal them in a ritual known as wikubema, as part of other more complex ceremonies, is common among the Rarámuri. Parts of plows, musical instruments, door locks, and nowadays crosses are made from juniper wood. Some Rarámuri eat the seed cones or drink a beverage tea made from them or the needles. Cupressus arizona (wa'á, Arizona cypress) is considered closely related to juniper/aborí and used for many of the same purposes.

The Swinomish, a Coast Salish tribe, reported used the decocted roots of J. scopulorum as a foot bath for rheumatism (Gunther 1973). A decoction of the needles was used as a fumigant in houses and to bathe ill people, and drunk as a general tonic. Apparently the Quileute, a Chimakum tribe, used the twigs and cones ceremonially. The X̱aayda (Haida) reportedly used J. communis for medicine and ceremony, though details are not available (Turner 2004).

The smoke for its branches were used in Britain, Scotland, and Ireland to prevent infections from spreading (Allen and Hatfield 2004; Darwin 2000).

Juniper seed cones are added to some varieties of sauerkraut in Germany (particularly Hasenbraaten, Rehbraten, and Schwabisches). Various Northern and Western European groups make beer including juniper cones, as do Sámi (Laplanders). Gin is of course made using juniper cones, and the name derives from the French word for juniper, genévrier. Other juniper-flavored spirits include Wacholder Branntwein (Germany, Austria, Switzerland), Vin de Genievre (France), and Juniper Hippocras or spiced wine (Northern Europe). Often the unripe, green female cones are used to make alcohol as the terpenoid levels are highest in these.

Juniper cones are covered with a whitish bloom which is a type of wild yeast. This can be used to ferment sugars into alcohol, as a sourdough starter, and to make other fermented foods.

It is generally considered a heating plant in traditional medical systems.

The Kalth Tindé or yát dìndé ("cedar/juniper people," Plains Apache) burned needles from J. pinchotii as incense during various rituals (Jordan 2008). This smoke was also commonly used around the home to ward off ghosts after the death of a family member, when thoughts of a dead relative could not be put aside, when a child was sick or crying inconsolably, or when an adult was sick or depressed. One informant suggested a decoction of leaves of juniper were used to stop bleeding after birth (echoing the use by some Rarámuri mentioned below), as well as to stop afterpains. The strong, rot-resistant wood of J. virginiana was prized for tipi poles, fence posts, drumsticks, skewers, staves, and flutes (heartwood). Obviously the connection with juniper was so close to these people they shared a name!

The Dzil Łigai Si'án Ndee (White Mountain Apache) reportedly used J. monosperma as an anticonvulsant, remedy for colds, flus, and coughs, and for unspecified female reproductive problems (Reagan 1929). They also ate the fruit as a food.

Juniper ash was mixed with Helenium hoopesii (sneezeweed) by the Diné to make a yellow dye (Shemluck 1982).

Ground stem of J. osteosperma was decocted together with stems of Tetradymia comosa (hairy horsebush) to treat upper respiratory tract infections by the Newe (Shoshone) (Shemluck 1982). Similarly the Paiute would combine young stems of J. osteosperma with the root of Wyethia mollis (wooly mule's ear') and decoct them for respiratory infections and fevers (Shemluck 1982). The Hopituh Shi-nu-mu (Hopi) made a tea of juniper and Artemisia filifolia (sand sagebrush) for indigestion (Shemluck 1982). The Diné (Navajo) would make a formula with Artemisia bigelovii (flat sagebrush), Artemisia carruthii (Carruth wormwood), Ceanothus fendleri (Fendler's red root), Tetradymia canescens (spineless horsebrush), Pinus spp (piñon pine), and juniper needles to protect from lightning, or possibly for extremely severe infections (Shemluck 1982). They also used spineless horsebrush leaf and juniper needles in a cold infusion for "ghost" infections, coughs, myalgias, indigestion, and respiratory infections (Shemluck 1982).

The Rarámuri (Tarahumara) say that a decoction of the needles and bark of J. pacyphlaea, J. deppeana or J. durangensis is emmenagogue and possibly abortifacient (Irigoyen-Rascón and Paredes 2015). A different community uses the same preparation to halt bleeding after delivery. Topical juniper needle poultice is used to treat impetigo. A decoction of needles is used internally for upper respiratory infections and coughs, and in a lotion for myalgia (direct topical application of tea also used this way), indigestion/stomach aches, respiratory infections, and pharyngitis. Juniper decoction was also used to protect fields from natural disasters (like hail) and to heal them from whatever ailments arose in the crops. Burning juniper boughs and exposing people, animals, and objects to the smoke to heal them in a ritual known as wikubema, as part of other more complex ceremonies, is common among the Rarámuri. Parts of plows, musical instruments, door locks, and nowadays crosses are made from juniper wood. Some Rarámuri eat the seed cones or drink a beverage tea made from them or the needles. Cupressus arizona (wa'á, Arizona cypress) is considered closely related to juniper/aborí and used for many of the same purposes.

The Swinomish, a Coast Salish tribe, reported used the decocted roots of J. scopulorum as a foot bath for rheumatism (Gunther 1973). A decoction of the needles was used as a fumigant in houses and to bathe ill people, and drunk as a general tonic. Apparently the Quileute, a Chimakum tribe, used the twigs and cones ceremonially. The X̱aayda (Haida) reportedly used J. communis for medicine and ceremony, though details are not available (Turner 2004).

The smoke for its branches were used in Britain, Scotland, and Ireland to prevent infections from spreading (Allen and Hatfield 2004; Darwin 2000).

Juniper seed cones are added to some varieties of sauerkraut in Germany (particularly Hasenbraaten, Rehbraten, and Schwabisches). Various Northern and Western European groups make beer including juniper cones, as do Sámi (Laplanders). Gin is of course made using juniper cones, and the name derives from the French word for juniper, genévrier. Other juniper-flavored spirits include Wacholder Branntwein (Germany, Austria, Switzerland), Vin de Genievre (France), and Juniper Hippocras or spiced wine (Northern Europe). Often the unripe, green female cones are used to make alcohol as the terpenoid levels are highest in these.

Juniper cones are covered with a whitish bloom which is a type of wild yeast. This can be used to ferment sugars into alcohol, as a sourdough starter, and to make other fermented foods.

Missouri River Region Native Uses (Gilmore 1911–1912)

Note: this source should be viewed with caution, as many ethnobotany texts compiled by white researchers were not always accurate for a multitude of reasons.

Juniperus virginiana L (cedar)

Hante or ḥante sha (Dakhótiyapi, formerly Dakota); sha, "red." Maazi (Pánka iyé, formerly Omaha-Ponca). Tawatsaako (Chaticks si Chaticks, formerly Pawnee).

The fruits are known as ḥante itika, "cedar eggs" [in Dakhótiyapi]. The fruits and leaves were boiled together and the decoction was used internally for coughs. It was given to horses also as a remedy for coughs. For a cold in the head twigs were burned and the smoke inhaled, the burning twigs and the head being enveloped in a blanket. Because the cedar tree is sacred to the mythical thunderbird, his nest being “in the cedar of the western mountains," cedar boughs were put on the tipi poles to ward off lightning, "as white men put up lightning rods," my informant said.

In the year 1849–50 Asiatic cholera was epidemic among the Teton Dakota [the Lakȟóta]. The Oglala [a Lakȟóta tribe] were encamped at that time where Pine Ridge Agency now is. Many of the people died and others scattered in a panic. Red Cloud [an Oglála Lakȟóta leader, whose indigenous name was Maȟpíya Lúta, 1822–1909], then a young man, tried various treatments, finally a decoction of cedar leaves. This was drunk and was used also for bathing, and is said to have proved a cure.

The Omaha-Ponca name for the cedar is maazi. Cedar twigs were used on the hot stones in the vapor bath, especially in purificatory rites. J. Owen Dorsey says, " In the Osage [Ni-u-kon-ska] traditions, cedar symbolizes the tree of life." Francis La Flesche says (Fletcher and La Flesche 1911):

"An ancient cedar pole was also in the keeping of the We'zhinshte gens, and was lodged in the Tent of War. This venerable object was once the central figure in rites that have been lost. In creation myths the cedar Is , associated with the advent of the human race; other mytha connect this tree with the thunder. The thunder birds were said to live "in a forest of cedars ..." There is a tradition that in olden times, in the spring after the first thunder had sounded, in the ceremony which then took place this Cedar Pole was painted and anointed at the great tribal festival held while on the buffalo hunt."

As a remedy for nervousness and bad dreams the Pawnee used the smoke treatment, burning cedar twigs for the purpose.

Note: this source should be viewed with caution, as many ethnobotany texts compiled by white researchers were not always accurate for a multitude of reasons.

Juniperus virginiana L (cedar)

Hante or ḥante sha (Dakhótiyapi, formerly Dakota); sha, "red." Maazi (Pánka iyé, formerly Omaha-Ponca). Tawatsaako (Chaticks si Chaticks, formerly Pawnee).

The fruits are known as ḥante itika, "cedar eggs" [in Dakhótiyapi]. The fruits and leaves were boiled together and the decoction was used internally for coughs. It was given to horses also as a remedy for coughs. For a cold in the head twigs were burned and the smoke inhaled, the burning twigs and the head being enveloped in a blanket. Because the cedar tree is sacred to the mythical thunderbird, his nest being “in the cedar of the western mountains," cedar boughs were put on the tipi poles to ward off lightning, "as white men put up lightning rods," my informant said.

In the year 1849–50 Asiatic cholera was epidemic among the Teton Dakota [the Lakȟóta]. The Oglala [a Lakȟóta tribe] were encamped at that time where Pine Ridge Agency now is. Many of the people died and others scattered in a panic. Red Cloud [an Oglála Lakȟóta leader, whose indigenous name was Maȟpíya Lúta, 1822–1909], then a young man, tried various treatments, finally a decoction of cedar leaves. This was drunk and was used also for bathing, and is said to have proved a cure.

The Omaha-Ponca name for the cedar is maazi. Cedar twigs were used on the hot stones in the vapor bath, especially in purificatory rites. J. Owen Dorsey says, " In the Osage [Ni-u-kon-ska] traditions, cedar symbolizes the tree of life." Francis La Flesche says (Fletcher and La Flesche 1911):

"An ancient cedar pole was also in the keeping of the We'zhinshte gens, and was lodged in the Tent of War. This venerable object was once the central figure in rites that have been lost. In creation myths the cedar Is , associated with the advent of the human race; other mytha connect this tree with the thunder. The thunder birds were said to live "in a forest of cedars ..." There is a tradition that in olden times, in the spring after the first thunder had sounded, in the ceremony which then took place this Cedar Pole was painted and anointed at the great tribal festival held while on the buffalo hunt."

As a remedy for nervousness and bad dreams the Pawnee used the smoke treatment, burning cedar twigs for the purpose.

Botanical Information

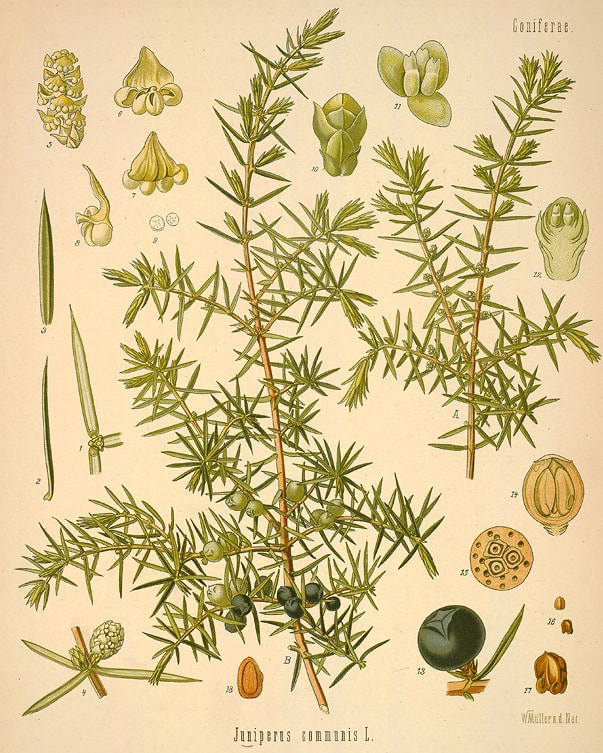

Botanical Description: Juniper can occur as a ground-hugging subshrub, shrub, or tree, depending on climactic conditions and elevation at which it grows. At its tallest, the tree rarely grows more than 3–4 m tall. Its leaves are reduced to bluish needles up to 20 mm long with a single white stomatal band on the undersurface. The tips of the needles are sharp.

This coniferous, non-flowering tree is dioecious (separate male and female trees). Female cones are the familiar rounded to elongate (4–12 mm diameter) bluish fruits used as medicine usually no more than 5--10 mm in diameter covered with a whitish, waxy bloom. They are made up of 3 (sometimes 6) fused scales. They start out green and slowly ripen over 12–18 mon (thus any particular tree with female structures will have a combination of unripe and ripe seed cones at any particular time of year) They contain from 1–3 seeds each. The male cones produce voluminous pollen which is borne by the wind to female cones and is highly allergenic. The leaves are needle-like (2–5 mm long, pointed), unlike most other junipers which have scale-like leaves. The thin bark is dark red brown and readily falls into loose scale-like chunks. All parts of the plant have a distinctive, pleasant juniper odor.

\textit{Juniperus} can be divided into two sections, Juniperus (needle-leaf junipers) and Sabina (scale-leaf junipers), with leaf morphology as described. Section Juniperus can be further divided into three subsections: Juniperus in which the female cones have three separate seeds and needles have one stomatal band, including J. communis}, J. conferta, and J. rigida; Oxycedrus (containing 8 Old World species) in which the female cones have three separate seeds and the needles have two stomatal bands; and Caryocedrus, in which the female cones have three seeds fused together and the needles have two stomatal bands, containing only J. drupacea (Syrian juniper). Section Sabina is divided into Old (20 species) and New (24 species) World groups.

Native range: Juniper is a native circumboreal species, found in north-central Eurasia stretching all the way to Korea and Japan, throughout Canada and the northern US up to and just beyond the Arctic Circle, and in mountainous regions of southern portions of North America. It is the only juniper species found native in both Eurasia and North America. Numerous other species in the genus are found in temperature and high desert climates in North America, as discussed in the Interchangeability of Species section above.

This coniferous, non-flowering tree is dioecious (separate male and female trees). Female cones are the familiar rounded to elongate (4–12 mm diameter) bluish fruits used as medicine usually no more than 5--10 mm in diameter covered with a whitish, waxy bloom. They are made up of 3 (sometimes 6) fused scales. They start out green and slowly ripen over 12–18 mon (thus any particular tree with female structures will have a combination of unripe and ripe seed cones at any particular time of year) They contain from 1–3 seeds each. The male cones produce voluminous pollen which is borne by the wind to female cones and is highly allergenic. The leaves are needle-like (2–5 mm long, pointed), unlike most other junipers which have scale-like leaves. The thin bark is dark red brown and readily falls into loose scale-like chunks. All parts of the plant have a distinctive, pleasant juniper odor.

\textit{Juniperus} can be divided into two sections, Juniperus (needle-leaf junipers) and Sabina (scale-leaf junipers), with leaf morphology as described. Section Juniperus can be further divided into three subsections: Juniperus in which the female cones have three separate seeds and needles have one stomatal band, including J. communis}, J. conferta, and J. rigida; Oxycedrus (containing 8 Old World species) in which the female cones have three separate seeds and the needles have two stomatal bands; and Caryocedrus, in which the female cones have three seeds fused together and the needles have two stomatal bands, containing only J. drupacea (Syrian juniper). Section Sabina is divided into Old (20 species) and New (24 species) World groups.

Native range: Juniper is a native circumboreal species, found in north-central Eurasia stretching all the way to Korea and Japan, throughout Canada and the northern US up to and just beyond the Arctic Circle, and in mountainous regions of southern portions of North America. It is the only juniper species found native in both Eurasia and North America. Numerous other species in the genus are found in temperature and high desert climates in North America, as discussed in the Interchangeability of Species section above.

Harvest, Cultivation, and Ecology

Cultivation: Cultivation is fairly extensive, though this is mostly for horticultural purposes and not growth for timber or medicine. Wild populations are ample around the North Hemisphere, though some areas (like northern UK) see decline while others see increases in the population. Harvesting the seed cones does not harm the trees, even with fairly intensive harvesting, so there is not much need for cultivation. If roots or bark started being used for medicine on any significant scale, cultivation might become necessary.

Wildcrafting: Juniper is extensively wildcrafted, and most seed cones can be removed from any particular tree, as taking the fruit does not harm the parent tree. Ultimately, if overharvested, the net population in the area may stop growing or might shrink, but this has basically not been observed in practice.

J. communis, J. oxycedrus, and other sharp-needled junipers (section Juniperus) are challenging to harvest. The sharp needles have to be avoided and ripe seed cones will fall off very easily. Placing a sheet on the ground around the tree to harvest will catch many of these errant cones; additionally the tree can simply be shaken to get many more to fall off intentionally. Wearing thick gloves and long sleeves protects against the needles. Scale-like leaved species are easier to harvest due to the lack of the prickly needles. Only ripe seed cones should be harvested for drying; unripe cones will spoil in this process. Unripe seed cones can be tinctured or steam distilled (the latter may even be desirable; General Council of Medical Education and Registration 1885).

Ecological Status: J. communis is the most widespread conifer in the world (Farjon 2005). This is likely due to its unusual berry-like seed cones, which are spread by birds over very large distances, including across land bridges between Eurasia and North America (Beringia and the North Atlantic, see Mao, et al. 2010 and Hantemirova, et al. 2012). It almost certainly originated in Eurasia and has spread to North America at least three times (Mao, et al. 2010). Juniper can and does survive in climates as varied as the far northern reaches of Canada to northern Mexico. It is not threatened in any way.

Wildcrafting: Juniper is extensively wildcrafted, and most seed cones can be removed from any particular tree, as taking the fruit does not harm the parent tree. Ultimately, if overharvested, the net population in the area may stop growing or might shrink, but this has basically not been observed in practice.

J. communis, J. oxycedrus, and other sharp-needled junipers (section Juniperus) are challenging to harvest. The sharp needles have to be avoided and ripe seed cones will fall off very easily. Placing a sheet on the ground around the tree to harvest will catch many of these errant cones; additionally the tree can simply be shaken to get many more to fall off intentionally. Wearing thick gloves and long sleeves protects against the needles. Scale-like leaved species are easier to harvest due to the lack of the prickly needles. Only ripe seed cones should be harvested for drying; unripe cones will spoil in this process. Unripe seed cones can be tinctured or steam distilled (the latter may even be desirable; General Council of Medical Education and Registration 1885).

Ecological Status: J. communis is the most widespread conifer in the world (Farjon 2005). This is likely due to its unusual berry-like seed cones, which are spread by birds over very large distances, including across land bridges between Eurasia and North America (Beringia and the North Atlantic, see Mao, et al. 2010 and Hantemirova, et al. 2012). It almost certainly originated in Eurasia and has spread to North America at least three times (Mao, et al. 2010). Juniper can and does survive in climates as varied as the far northern reaches of Canada to northern Mexico. It is not threatened in any way.

References

Aliev AM, Radjabov GK, Musaev AM (2015) "Dynamics of supercritical extraction of biological active substances from the Juniperus communis var saxatillis" J Supercritical Fluids 102:66–72.

Allen D, Hatfield G (2004) Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition, An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Timber Press).

Anonymous (2001) "Final report on the safety assessment of Juniperus communis Extract, Juniperus oxycedrus Extract, Juniperus oxycedrus Tar, Juniperus phoenicea extract, and Juniperus virginiana Extract" Int J Toxicol 20(Suppl 2):41–56.

Bais S, Gill NS, Kumar N (2015) "Neuroprotective Effect of Juniperus communis on chlorpromazine induced Parkinson disease in animal model" Chinese J Biol 2015:542542.

Begay D (2017) Quanitification and comparison of calcium in juniper ash and soil used in traditional Navajo foods. Masters thesis, Northern Arizona University.

Carpenter CD, O'Neill T, Picot N, et al. (2012) "Anti-mycobacterial natural products from the Canadian medicinal plant Juniperus communis" J Ethnopharmacol 143(2):695–700.

Clark AM, McChesney JD, Adams RP (1990) "Antimicrobial properties of heartwood, bark/sapwood and leaves of Juniperus species" Phytother Res 4(1):15–19.

Darwin T (2000) The Scots Herbal—The Plant Lore of Scotland (Edinburgh: Mercat Press).

Digrak M, Ilcim A, Alma MH (1999) "Antimicrobial activities of several parts of Pinus brutia, Juniperus oxycedrus, Abies cilicia, Cedrus libani and Pinus nigra" Phytother Res 13:584–7.

Farjon A (2005) A monograph of Cupressaceae and Sciadopitys (Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens).

Felter HW (1922) Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, reprinted 1998).

Fletcher AC, La Flesche F (1911) The Omaha Tribe Vol 1 (Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, reprinted 1972 by the University of Nebraska Press).

General Council of Medical Education and Registration (1885) The British Pharmacopoeia (London: Spottiswoode and Co).

Gilmore MR (1911–1912) Use of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region (33rd annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Government Printing Office, 1919).

Gordien AY, Graya AI, Franzblau SG, Seidel V (2009) "Antimycobacterial terpenoids from Juniperus communis L (Cuppressaceae)" J Ethnopharmacol 126(3):500–5.

Gordien AY, Gray AI, Ingleby K, et al. (2010) "Activity of Scottish plant, lichen and fungal endophyte extracts against Mycobacterium aurum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis" Phytother Res 24(5):692–8.

Gunther E (1973) Ethnobotany of Western Washington: The Knowledge and Use of Indigenous Plants by Native Americans (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

Hantemirova EV, Berkutenko AN, Semerikov VL (2012) "Systematics and gene geography of Juniperus communis L inferred from isoenzyme data" Russian J Genet 48(9):920–6.

Irigoyen-Rascón F, Paredes A (2015) Tarahumara Medicine: Ethnobotany and Healing Among the Rarámuri of Mexico (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Janku I, Hava M, Kraus R, Motl O (1960) "The diuretic principle of juniper" Arch Expl Pathol Pharmakol 238:112–3 [in German].

Janku I, Hava M, Motl O (1957) "An effective diuretic substance from juniper (Juniperus communis L)" Experientia 13:522–34 [in German].

Jimenez-Arellanes A, Meckes M, Ramirez R, et al. (2003) "Activity against multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Mexican plants used to treat respiratory diseases" Phytother Res 17(8):903–8.

Johnston WH, Karchesy JJ, Constantine GH, Craig AM (2001) "Antimicrobial activity of some Pacific Northwest woods against anaerobic bacteria and yeast" Phytother Res 15:586--568.

Jordan JA (2008) Plains Apache Ethnobotany (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Karaman İ, Şahin F, Güllüce M, et al. (2003) "Antimicrobial activity of aqueous and methanol extracts of Juniperus oxycedrus L" J Ethnopharmacol 85(2--3):231--235.

Köhler FE (1887) Medizinal-Pflanzen in naturgetreuen Abbildungen mit kurz erläuterndem Texte: Atlas zur Pharmacopoea germanica (Leipzig: Gera-Untermhaus), illustrated by Müller L, Schmidt CF, and Gunther K.

Lasheras B, Turillas P, Cenarruzabeitia E (1986) "Preliminary pharmacological study of Prunus spinosa L, Amelianchier ovalis Medikus, Juniperus communis L and Urtica dioica L" Plantes Med Phytother 20:219–26 [in French].

Mao K, Hao G, Liu J, et al. (2010) "Diversification and biogeography of Juniperus (Cupressaceae): Variable diversification rates and multiple intercontinental dispersals" New Phytol 188(1):254–72.

Moore M (1989) Medicinal Plants of the Desert and Canyon West (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press).

Orhan N, Orhan IE, Ergun F (2011) "Insights into cholinesterase inhibitory and antioxidant activities of five Juniperus species" Food Chem Toxicol 49:2305–12.

Parvizi MM, Handjani F, Moein M, et al. (2017) "Efficacy of cryotherapy plus topical Juniperus excelsa M Bieb cream versus cryotherapy plus placebo in the treatment of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis: A triple-blind randomized controlled clinical trial" PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11(10):e0005957.

Reagan AB (1929) "Plants Used by the White Mountain Apache Indians of Arizona" Wisconsin Archeologist 8:143–61.

Renaux J, La Barre J (1941) "Regarding the oxytocic effects of essences of rue and savin" Acta Biol Belg 1:334–5 [in French].

Schilcher H, Boesel R, Effenberger S, Segebrecht S (1989) "Neuere Untersuchungsergebnisse mit aquaretisch, antibakteriell und prostarop wirksamen Arzneipflanzen" Z Phytother 10:77–82 [in German].

Schilcher H, Emmrich D, Koehler C (1993) "GLC comparison of commercially available juniper oils and their toxicological evaluation" Pz Wiss 138(3–4):85–91 [in German].

Schilcher H, Leuschner F (1997) "The potential nephrotoxic effects of essential juniper oil" Arzneim Forsch 47(7):855–8 [in German].

Shemluck M (1982) "Medicinal and Other Uses of the Compositae By Indians in the United States and Canada" J Ethnopharmacol 5:303–58.

Singh H, Prakash A, Kalia AN, Majeed ABA (2016) "Synergistic hepatoprotective potential of ethanolic extract of Solanum xanthocarpum and Juniperus communis against paracetamol and azithromycin induced liver injury in rats" J Trad Complemen Med 6:370–6.

Sposato B, Scalese M (2013) "Prevalence and real clinical impact of Cupressus sempervirens and Juniperus communis sensitisations in Tuscan 'Maremma', Italy" Allerg Immunopath 41(1):17–24.

Stanic G, Samarzija I, Blazevic N (1998) "Time-dependent diuretic response in rats treated with juniper berry preparations" Phytother Res 12:494–7.

Stassi V, Verykokidou E, Loukis A, et al. (1996) "The antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of four Juniperus species growing wild in Greece" Flavour Fragrance J 11:71--74.

Taviano MF, Marino A, Trovato A, et al. (2013) "Juniperus oxycedrus L subsp oxycedrus and Juniperus oxycedrus L subsp macrocarpa (Sibth \& Sm) Ball 'berries' from Turkey: Comparative evaluation of phenolic profile, antioxidant, cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities" Food Chem Toxicol 58:22–9.

Tisserand R, Balacs T (1995) Essential Oil Safety: A Guide for Health Care Professionals (Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone):142.

Turner NW (2004) Plants of Haida Gwaii (X̱aadaa Gwaay gud gina ḵ'aws) (Winlaw, BC: Sononis Press).

Uehleke B (1996) "Phytobalneology" Z Phytother 17(1):26–43.

Ved A, Gupta A, Rawat ASK (2017) "Antioxidant and hepatoprotective potential of phenol-rich fraction of Juniperus communis Linn leaves" Pharmacogn Mag 13(49):108--113.

Volmor H, Giebel A (1938) "The diuretic action of several combinations of juniper berry and ononis root" Arch Explt Path Pharmakol 190:522–34.

Weiss RF (1988) Herbal Medicine (Gothenburg, Sweden: Ab Arcanum and Beaconsfield, UK: Beaconsfield Publishers Ltd).

Whitney TR, Wildeus S, Zajac AM (2013) "The use of redberry juniper (Juniperus pinchotii) to reduce Haemonchus contortus fecal egg counts and increase ivermectin efficacy" Vet Parasitol 197(1–2):182–8.

Allen D, Hatfield G (2004) Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition, An Ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Timber Press).

Anonymous (2001) "Final report on the safety assessment of Juniperus communis Extract, Juniperus oxycedrus Extract, Juniperus oxycedrus Tar, Juniperus phoenicea extract, and Juniperus virginiana Extract" Int J Toxicol 20(Suppl 2):41–56.

Bais S, Gill NS, Kumar N (2015) "Neuroprotective Effect of Juniperus communis on chlorpromazine induced Parkinson disease in animal model" Chinese J Biol 2015:542542.

Begay D (2017) Quanitification and comparison of calcium in juniper ash and soil used in traditional Navajo foods. Masters thesis, Northern Arizona University.

Carpenter CD, O'Neill T, Picot N, et al. (2012) "Anti-mycobacterial natural products from the Canadian medicinal plant Juniperus communis" J Ethnopharmacol 143(2):695–700.

Clark AM, McChesney JD, Adams RP (1990) "Antimicrobial properties of heartwood, bark/sapwood and leaves of Juniperus species" Phytother Res 4(1):15–19.

Darwin T (2000) The Scots Herbal—The Plant Lore of Scotland (Edinburgh: Mercat Press).

Digrak M, Ilcim A, Alma MH (1999) "Antimicrobial activities of several parts of Pinus brutia, Juniperus oxycedrus, Abies cilicia, Cedrus libani and Pinus nigra" Phytother Res 13:584–7.

Farjon A (2005) A monograph of Cupressaceae and Sciadopitys (Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens).

Felter HW (1922) Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications, reprinted 1998).

Fletcher AC, La Flesche F (1911) The Omaha Tribe Vol 1 (Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, reprinted 1972 by the University of Nebraska Press).

General Council of Medical Education and Registration (1885) The British Pharmacopoeia (London: Spottiswoode and Co).

Gilmore MR (1911–1912) Use of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region (33rd annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Government Printing Office, 1919).

Gordien AY, Graya AI, Franzblau SG, Seidel V (2009) "Antimycobacterial terpenoids from Juniperus communis L (Cuppressaceae)" J Ethnopharmacol 126(3):500–5.

Gordien AY, Gray AI, Ingleby K, et al. (2010) "Activity of Scottish plant, lichen and fungal endophyte extracts against Mycobacterium aurum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis" Phytother Res 24(5):692–8.

Gunther E (1973) Ethnobotany of Western Washington: The Knowledge and Use of Indigenous Plants by Native Americans (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

Hantemirova EV, Berkutenko AN, Semerikov VL (2012) "Systematics and gene geography of Juniperus communis L inferred from isoenzyme data" Russian J Genet 48(9):920–6.

Irigoyen-Rascón F, Paredes A (2015) Tarahumara Medicine: Ethnobotany and Healing Among the Rarámuri of Mexico (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Janku I, Hava M, Kraus R, Motl O (1960) "The diuretic principle of juniper" Arch Expl Pathol Pharmakol 238:112–3 [in German].

Janku I, Hava M, Motl O (1957) "An effective diuretic substance from juniper (Juniperus communis L)" Experientia 13:522–34 [in German].

Jimenez-Arellanes A, Meckes M, Ramirez R, et al. (2003) "Activity against multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Mexican plants used to treat respiratory diseases" Phytother Res 17(8):903–8.

Johnston WH, Karchesy JJ, Constantine GH, Craig AM (2001) "Antimicrobial activity of some Pacific Northwest woods against anaerobic bacteria and yeast" Phytother Res 15:586--568.

Jordan JA (2008) Plains Apache Ethnobotany (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Karaman İ, Şahin F, Güllüce M, et al. (2003) "Antimicrobial activity of aqueous and methanol extracts of Juniperus oxycedrus L" J Ethnopharmacol 85(2--3):231--235.

Köhler FE (1887) Medizinal-Pflanzen in naturgetreuen Abbildungen mit kurz erläuterndem Texte: Atlas zur Pharmacopoea germanica (Leipzig: Gera-Untermhaus), illustrated by Müller L, Schmidt CF, and Gunther K.

Lasheras B, Turillas P, Cenarruzabeitia E (1986) "Preliminary pharmacological study of Prunus spinosa L, Amelianchier ovalis Medikus, Juniperus communis L and Urtica dioica L" Plantes Med Phytother 20:219–26 [in French].

Mao K, Hao G, Liu J, et al. (2010) "Diversification and biogeography of Juniperus (Cupressaceae): Variable diversification rates and multiple intercontinental dispersals" New Phytol 188(1):254–72.

Moore M (1989) Medicinal Plants of the Desert and Canyon West (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press).

Orhan N, Orhan IE, Ergun F (2011) "Insights into cholinesterase inhibitory and antioxidant activities of five Juniperus species" Food Chem Toxicol 49:2305–12.