by Eric Yarnell, ND, RH(AHG)

Last updated 17 Feb 2022

This monograph is protected by copyright and is intended only for use by health care professionals and students. You may link to this page if you are sharing it with others in health care, but may not otherwise copy, alter, or share this material in any way. By accessing this material you agree to hold the author harmless for any use of this information. Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site. Please donate to help support the extensive amount of time and energy it takes to create and maintain this site.

Table of Contents

Clinical Highlights

Devil's club is a revered medicine among the native peoples of the Pacific Northwestern US and Canada.

Devil's club root bark is immunomodulating, adaptogenic, and insulin sensitizing.

Devil's club is used for people with cancer, autoimmune conditions, those suffering the effects of uncompensated stress, and those with insulin resistance.

Devil's club generally has minimal adverse effects beyond occasional nausea or insomnia.

Devil's club root bark is immunomodulating, adaptogenic, and insulin sensitizing.

Devil's club is used for people with cancer, autoimmune conditions, those suffering the effects of uncompensated stress, and those with insulin resistance.

Devil's club generally has minimal adverse effects beyond occasional nausea or insomnia.

Clinical Fundamentals

Part Used: the root bark is most traditionally used, preferably fresh but carefully dried is acceptable. The stem bark (with prickles pounded off) is moderately inferior but somewhat more sustainable, again preferably fresh but carefully dried is acceptable. There is emerging evidence that the fruit may also be usable.

Taste: soapy, acrid, and unpleasant.

Major Actions:

Among the adaptogens, Oplopanax horridus can be distinguished by being mildly stimulating and having a respiratory tract affinity.

Major Organ System Affinities

Major Indications:

One tiny study (n=4) did not find a short-term hypoglycemic effect from drinking devil's club tea (approximately 80 ml, but no details on tea preparation were provided) in people with diabetes (Thommassen, et al. 1990). Other older reports also did not find a hypoglycemic effect from devil's club (Stuhr and Henry 1944; Piccoli, et al. 1940). Modern, adequately-powered trials looking at various doses and dose forms, and using multiple outcome measures rather than just short-term serum glucose readings, are urgently needed.

Major Constituents: (Wu, et al. 2018; Calway, et al. 2012)

Adverse Effects: Mild nausea or insomnia may occur, albeit very rarely. The vast majority of people who take this have no adverse effects. The biggest problems come in harvesting and working with the plant, and the injuries the stem prickles can cause in such a setting (see Cultivation section below).

Contraindications: There are no clearly documented contraindications. Its use in pregnancy and lactation are poorly documented

Drug Interactions: There are no documented drug interactions. There is potential for this to increase the potency of insulin and hypoglycemic drugs, so have patients monitor their blood glucose levels carefully if they are taking those drugs and start on devil's club.

Taste: soapy, acrid, and unpleasant.

Major Actions:

- Adaptogen

- Immunomodulator

- Insulin sensitizing

- Antimicrobial

Among the adaptogens, Oplopanax horridus can be distinguished by being mildly stimulating and having a respiratory tract affinity.

Major Organ System Affinities

- Respiratory Tract

Major Indications:

- Upper and lower respiratory infections, prevention and treatment

- Cancer treatment (possibly prevention) (Lantz, et al. 2004)

- Autoimmune diseases

- Diabetes mellitus

One tiny study (n=4) did not find a short-term hypoglycemic effect from drinking devil's club tea (approximately 80 ml, but no details on tea preparation were provided) in people with diabetes (Thommassen, et al. 1990). Other older reports also did not find a hypoglycemic effect from devil's club (Stuhr and Henry 1944; Piccoli, et al. 1940). Modern, adequately-powered trials looking at various doses and dose forms, and using multiple outcome measures rather than just short-term serum glucose readings, are urgently needed.

Major Constituents: (Wu, et al. 2018; Calway, et al. 2012)

- Polyynes, polyacetylenes

- Phenylpropanoids and their glycosides

- Lignan glycosides

- Sesquitepenes, predominantly (S, E)-nerolidol

- Triterpenoid glycosides (identified only in the leaves, not the root, stem, or bark)

Adverse Effects: Mild nausea or insomnia may occur, albeit very rarely. The vast majority of people who take this have no adverse effects. The biggest problems come in harvesting and working with the plant, and the injuries the stem prickles can cause in such a setting (see Cultivation section below).

Contraindications: There are no clearly documented contraindications. Its use in pregnancy and lactation are poorly documented

Drug Interactions: There are no documented drug interactions. There is potential for this to increase the potency of insulin and hypoglycemic drugs, so have patients monitor their blood glucose levels carefully if they are taking those drugs and start on devil's club.

Pharmacy Essentials

Tincture: 1:2–1:3 w:v ratio, 30% ethanol

Dose:

Acute, adult: 1–3 ml qid or more frequently

Chronic, adult: 1–3 ml tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Glycerite: 1:3 w:v ratio, 75%+ vegetable glycerin

Dose: same as for tincture

Decoction: 5 g (1 tbsp) of cut and sifted root bark simmered, covered, in 250–500 ml of water for 15–30 min, the result of which makes one cup (not 8 oz, but one dose). The amount of water used can be adjusted to patient taste in subsequent cups.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup qid or more frequently

Chronic, adult: 1 cup tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Capsules: these are not widely available.

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Dose:

Acute, adult: 1–3 ml qid or more frequently

Chronic, adult: 1–3 ml tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Glycerite: 1:3 w:v ratio, 75%+ vegetable glycerin

Dose: same as for tincture

Decoction: 5 g (1 tbsp) of cut and sifted root bark simmered, covered, in 250–500 ml of water for 15–30 min, the result of which makes one cup (not 8 oz, but one dose). The amount of water used can be adjusted to patient taste in subsequent cups.

Dose:

Acute adult: 1 cup qid or more frequently

Chronic, adult: 1 cup tid

Child: as adult but adjusted for body size

Capsules: these are not widely available.

If you need help formulating with this herb, or any other, you can use the formulation tool. Remember that when using this herb in a formula, due to synergy, you can usually use less.

Other Names

Latin synonyms:

Current correct Latin binomial: Oplopanx horridus (Sm) Miq

Aralia erinacea Hook

Aralia occidentalis Schltdl ex Ledeb

Echinopanax horridus (Sm) Decne. & Planch ex Harms

Fatsia horrida Benth & Hook f

Horsfieldia horrida (Sm) Seem

Panax horridus Sm

Ricinophyllum americanum Pall ex Ledeb

Ricinophyllum horridum A Nelson & JF Macbr

English Common Names: devil's club (referring to the nasty prickles on the stem)

Do not confuse this with Harpagophytum procumbens (devil's claw), a South African plant used for arthritis. They really have nothing in common, but some people confuse the common names.

Native American Common Names (grouped linguistically and geographically):

Atna' kenaege' (Ahtna, Athabascan): xos cogh

Dena’ina Qenaga (Tanaina, Athabascan): xeshkeghkaʔa (“prickle very big” in Upper and Outer Inlet dialects); heskhegh (“prickle big” in Inner Inlet dialect)

Dakeł ᑕᗸᒡ (Southern Carrier, Athabascan): hudai, hułghəł, huł ghəł, whəscho, whəscho tʔan

Tse'khene (Sekani, Athabascan): whush cho (“big thorn”)

Tałtan ẕāke (Tahltan, Athabascan): khos choo, xʷus choo, khuschoo

Witsuwit’en (Northern Carrier, Athabascan): whis tso; whisco (“big thorn”)

Łingít (Tlingit, Tlingit family): s’áxt’, áchta

Gitxsanimaax (Tsimshian, Tsimshian family): huʔums, wəʔuumst, haʔums (Eastern dialect); waʔumst (Western dialect)

nisqáʔamq (Nishga, Tsimshian): waʔums

Sm’álgyax (Tsimshian, Tsimshian language): wooms

Sgüüx̣s, (Southern Tsimshian, Tsimshian): wóoʔms, wóoʔmms (root); sxáwó́oʔms (shrub)

diitiid7aa7tx (Ditidaht, Wakashan): ʕayxʷqʷapt (“codfish lure plant”), qʔuuquyʔaatskapt (“codfish lure plant”)

ɦiɬtsʰaqʷ (Bella Bella, Wakashan): wíqʔás

Kwak̓wala, Kwak’walaKwakiutl, Wakashan): ʔixʷmiy

qʷi·qʷi·diččaq, qwiqwidicciat (Makah, Wakashan): haaʔałbap (“fishing lure plant”)

T̓aat̓aaqsapa, nuučaan̓uɫ (Nootka or Nuu-chah-nulth, Wakashan): nʔaapʔaałmapt

ʔuwíkʼala (Oowekyala, Wakashan): wìqʔas

Hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, Hul̓q̓umín̓um̓ or Halq̓eméylem (Halkomelem, Salish): qwó:pelhp; qwa’pulhp (island dialects); qʷáʔpəłp (Quw’utsun dialect); qʷáapəłp (upriver dialect)

dxʷləšúcid, xʷləšúcid (Lushootseed, Salish): sx̱ədíʔats, xadíaʔts, xadíaʔts, čičáčilú (Snuqualmie dialect)

ńseĺxčiń (Colville-Okanagan, Salish): xaxaʕáy̓łp, xʷuxʷuʕʷáy̓łp

Nəxʷsƛ̓ay̓əmúcən (Klallam, Salish): puqłč, púʔqʷłč

Nlaka'pamuctsin (Thompson, Salish): k̓étyeʔ

Nuxalk (Bella Coola, Salish): sk̓äłk’; tskʔałkʷ (< stskʔ “fir bark slivers”); skʔalk (plant); stʔls tin an (fruit, “highbush cranberries of grizzlies”)

Q̉ʷay̓áyiłq̉ (Upper Chehalis, Salish): pəsʔáynł (<pə́saʔ “monster, evil spirit”)

ʔayajuθəm (Comox Salish, Salish): č̓íʔt̓ay

Šecwepemctšín (Shuswap, Salish): (s)k̓etseʔełp (Western dialect); (s)k̓etsəʔéłp (Eastern dialect); sʷuxʷéləqʷ (“smell wood”)

SENĆOŦEN, sənčáθən (Saanich, North Straits Salish dialect): qʷáʔpəłč

Shíshalh (Sechelt, Salish): č̓ʔát̓ay, č̓áʔat̓ay (root or shrub); č̓áʔat̓ayíya (leaf)

Séliš (Spokane-Kalispel-Pend d’Oreille, Salish): xoxoʔíłp, xʷuxʷugʷáy̓łp

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim (Squamish, Salish): č̓átiyay̓

sƛ̓áƛ̓y̌əmx (Lillooet, Salish): k̓átł–az̓ (shrub, Pemberton dialect); məx–máx (“spines,” Fraser River and Pemberton dialects)

təw'ánəxʷ (Skokomish or Twana, Salish): sp̓bqe’pi

W̱LEMI,ĆOSEN, xʷləmiʔčósən (Lummi, North Straits Salish dialect): qwún̓numpł

Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit (Yakama, Sahaptin): šqapqápnu–waaaš (“rash bush”)

Sł'púlmš (Lower Cowlitz, Sahaptin): sqaipqáipas

Ktunaxa (Kutenai, Isolate): naǂi:tsaxawuk, naǂi:tsaxawuʔk, nałiytsaxawuʔk

X̱aat Kíl (Haida, Isolate): hʔuìqʔas (shrub); hʔuiqtuài (fruit, “bear’s berries”); ts’iihlinjaaw, ts’iiłanjaaw (Massett dialect); ts’iihllnjaaw, ts’iihlinjaaw, ts’iiłanjaaw (Skidegate dialect); ts’iiłanjaaw (< ts’iihl “gambling sticks”)

Current correct Latin binomial: Oplopanx horridus (Sm) Miq

Aralia erinacea Hook

Aralia occidentalis Schltdl ex Ledeb

Echinopanax horridus (Sm) Decne. & Planch ex Harms

Fatsia horrida Benth & Hook f

Horsfieldia horrida (Sm) Seem

Panax horridus Sm

Ricinophyllum americanum Pall ex Ledeb

Ricinophyllum horridum A Nelson & JF Macbr

English Common Names: devil's club (referring to the nasty prickles on the stem)

Do not confuse this with Harpagophytum procumbens (devil's claw), a South African plant used for arthritis. They really have nothing in common, but some people confuse the common names.

Native American Common Names (grouped linguistically and geographically):

Atna' kenaege' (Ahtna, Athabascan): xos cogh

Dena’ina Qenaga (Tanaina, Athabascan): xeshkeghkaʔa (“prickle very big” in Upper and Outer Inlet dialects); heskhegh (“prickle big” in Inner Inlet dialect)

Dakeł ᑕᗸᒡ (Southern Carrier, Athabascan): hudai, hułghəł, huł ghəł, whəscho, whəscho tʔan

Tse'khene (Sekani, Athabascan): whush cho (“big thorn”)

Tałtan ẕāke (Tahltan, Athabascan): khos choo, xʷus choo, khuschoo

Witsuwit’en (Northern Carrier, Athabascan): whis tso; whisco (“big thorn”)

Łingít (Tlingit, Tlingit family): s’áxt’, áchta

Gitxsanimaax (Tsimshian, Tsimshian family): huʔums, wəʔuumst, haʔums (Eastern dialect); waʔumst (Western dialect)

nisqáʔamq (Nishga, Tsimshian): waʔums

Sm’álgyax (Tsimshian, Tsimshian language): wooms

Sgüüx̣s, (Southern Tsimshian, Tsimshian): wóoʔms, wóoʔmms (root); sxáwó́oʔms (shrub)

diitiid7aa7tx (Ditidaht, Wakashan): ʕayxʷqʷapt (“codfish lure plant”), qʔuuquyʔaatskapt (“codfish lure plant”)

ɦiɬtsʰaqʷ (Bella Bella, Wakashan): wíqʔás

Kwak̓wala, Kwak’walaKwakiutl, Wakashan): ʔixʷmiy

qʷi·qʷi·diččaq, qwiqwidicciat (Makah, Wakashan): haaʔałbap (“fishing lure plant”)

T̓aat̓aaqsapa, nuučaan̓uɫ (Nootka or Nuu-chah-nulth, Wakashan): nʔaapʔaałmapt

ʔuwíkʼala (Oowekyala, Wakashan): wìqʔas

Hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, Hul̓q̓umín̓um̓ or Halq̓eméylem (Halkomelem, Salish): qwó:pelhp; qwa’pulhp (island dialects); qʷáʔpəłp (Quw’utsun dialect); qʷáapəłp (upriver dialect)

dxʷləšúcid, xʷləšúcid (Lushootseed, Salish): sx̱ədíʔats, xadíaʔts, xadíaʔts, čičáčilú (Snuqualmie dialect)

ńseĺxčiń (Colville-Okanagan, Salish): xaxaʕáy̓łp, xʷuxʷuʕʷáy̓łp

Nəxʷsƛ̓ay̓əmúcən (Klallam, Salish): puqłč, púʔqʷłč

Nlaka'pamuctsin (Thompson, Salish): k̓étyeʔ

Nuxalk (Bella Coola, Salish): sk̓äłk’; tskʔałkʷ (< stskʔ “fir bark slivers”); skʔalk (plant); stʔls tin an (fruit, “highbush cranberries of grizzlies”)

Q̉ʷay̓áyiłq̉ (Upper Chehalis, Salish): pəsʔáynł (<pə́saʔ “monster, evil spirit”)

ʔayajuθəm (Comox Salish, Salish): č̓íʔt̓ay

Šecwepemctšín (Shuswap, Salish): (s)k̓etseʔełp (Western dialect); (s)k̓etsəʔéłp (Eastern dialect); sʷuxʷéləqʷ (“smell wood”)

SENĆOŦEN, sənčáθən (Saanich, North Straits Salish dialect): qʷáʔpəłč

Shíshalh (Sechelt, Salish): č̓ʔát̓ay, č̓áʔat̓ay (root or shrub); č̓áʔat̓ayíya (leaf)

Séliš (Spokane-Kalispel-Pend d’Oreille, Salish): xoxoʔíłp, xʷuxʷugʷáy̓łp

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim (Squamish, Salish): č̓átiyay̓

sƛ̓áƛ̓y̌əmx (Lillooet, Salish): k̓átł–az̓ (shrub, Pemberton dialect); məx–máx (“spines,” Fraser River and Pemberton dialects)

təw'ánəxʷ (Skokomish or Twana, Salish): sp̓bqe’pi

W̱LEMI,ĆOSEN, xʷləmiʔčósən (Lummi, North Straits Salish dialect): qwún̓numpł

Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit (Yakama, Sahaptin): šqapqápnu–waaaš (“rash bush”)

Sł'púlmš (Lower Cowlitz, Sahaptin): sqaipqáipas

Ktunaxa (Kutenai, Isolate): naǂi:tsaxawuk, naǂi:tsaxawuʔk, nałiytsaxawuʔk

X̱aat Kíl (Haida, Isolate): hʔuìqʔas (shrub); hʔuiqtuài (fruit, “bear’s berries”); ts’iihlinjaaw, ts’iiłanjaaw (Massett dialect); ts’iihllnjaaw, ts’iihlinjaaw, ts’iiłanjaaw (Skidegate dialect); ts’iiłanjaaw (< ts’iihl “gambling sticks”)

Interchangeability of Species

Oplopanax elatus Nakai = Echinopanax elatus Nakai = O. horridus ssp elatus Hara (Asian devil's club, 刺参 cì shēn), found in Siberia and Northern Korea, and Oplopanax japonicus = O. horridus ssp brevilobus H Hara (Japanese devil's club) are reported as having adaptogenic effects, and are utilized for people with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and prevention of infection (Baranov 1982). O. elatus is threatened in the wild, however, and only cultivated material should be used.

Advanced Clinical Information

Additional Actions:

Additional Indications:

For a thorough treatment of ethnobotanical uses, see the reviews by Turner 1982 and Lantz, et al. 2004.

Diabetes mellitus type 2 is believed to have rarely occurred in the Americas prior to the European invasion. However, since the imposition of the western lifestyle on native peoples and many layers of attempted genocide against them, diabetes has become common (diabetes mellitus type 1 is still very rare in these populations). There are historical reports of use of devil's club by Native Americans to keep diabetes at bay (Vogel 1970; MacDermot 1949). This highlights that tradition is not static, that as new problems arise, old medicines are put to new uses. So as diabetes became prevalent, this herb was determined to have a likely to help and was adopted for this purpose. But prior to that, there was no need for such a use as the disease was rare or non-existent.

The prickly branches were and are used as spiritual wards, often being placed over doorways, under a mattress, or in the corners of a room to keep out evil.

- Anti–respiratory syncytial virus (McCutcheon, et al. 1995)

- Anti–mycobacterial (Kobaisy, et al. 1997; McCutcheon, et al. 1997); synergy has been shown among some compounds (Inui, et al. 2007)

- Antioxidant (Tai, et al. 2006)

- Antineoplastic (Tai, et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2013; Huang, et al. 2014; Wu, et al. 2018)

- Anti-leukemic (McGill, et al. 2014)

- Not phytoestrogenic (Graham and Noble 1955)

Additional Indications:

- Tuberculosis

- Cancer

For a thorough treatment of ethnobotanical uses, see the reviews by Turner 1982 and Lantz, et al. 2004.

Diabetes mellitus type 2 is believed to have rarely occurred in the Americas prior to the European invasion. However, since the imposition of the western lifestyle on native peoples and many layers of attempted genocide against them, diabetes has become common (diabetes mellitus type 1 is still very rare in these populations). There are historical reports of use of devil's club by Native Americans to keep diabetes at bay (Vogel 1970; MacDermot 1949). This highlights that tradition is not static, that as new problems arise, old medicines are put to new uses. So as diabetes became prevalent, this herb was determined to have a likely to help and was adopted for this purpose. But prior to that, there was no need for such a use as the disease was rare or non-existent.

The prickly branches were and are used as spiritual wards, often being placed over doorways, under a mattress, or in the corners of a room to keep out evil.

Reported Ethnobotanical Uses of Oplopanax horridus

| Group | Use(s) | Reference(s) |

| Dena'ina (Tanaina) of Kenai | fever | Kari 1977 |

| Dena'ina (Tanaina) of Upper Cook Inlet | TB, cough, nausea, fever, boils, sores | Kari 1977 |

| Gitxsan | General health tonic, revitalizer, rheumatic, wounds, stomach pain, ulcers, for good luck, for purification | Johnson 1997; Gottesfeld and Anderson 1998 |

| Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw (Kwakiutl) | body paint | Turner and Bell 1973 |

| Łingit (Tlingit) | emetic, purgative, sores | de Laguna 1972 |

| nłaʔkápməx (Thompson) | appetite stimulant | Turner, et al. 1990 |

| Nuxalk (Bella Coola) | rheumatism, nausea, diabetes | Turner 1973; MacDermot 1949 |

| X̱aayda (Haida) | rheumatism, nausea, diabetes | Turner 1973; MacDermot 1949 |

No definitive, published reference to traditional use of devil's club for diabetes could be found prior to that of MacDermot 1949. The animal study by Large and Brocklesby from 1938 was based on the case of a man who became diabetic while hospitalized for surgery and who previously had been able to drink devil's club bark tea every day for years prior and who was able to return to good health once able to return to this habit, but they stated the man involved had not explicitly been doing this to treat diabetes.

Botanical Information

Botanical Description: This large, evergreen shrub grows in thickets up to 3 m tall. Very large leaves (up to 30 cm wide), deeply indented with long prickles on the stem and leaf veins. These are prickles and not spines, as the prickles contain no vascular tissue. Flowers in late spring/early summer. Monoecious. Greenish-white flowers in clusters up to 30 cm long. Bright red clusters of berries follow in the summer. It spreads through rhizomes, decumnbent stems, and seed. It is drought intolerant.

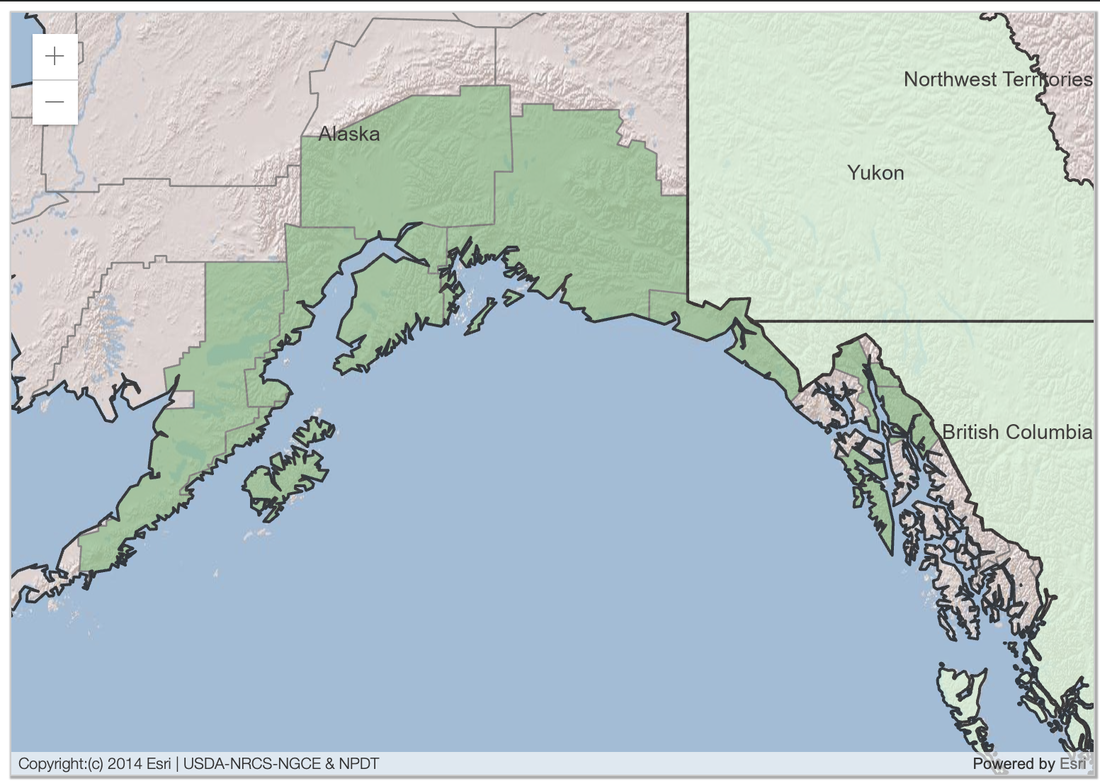

Native range: Devil's club grows in wet, rocky ravines or riparian habitats in the Pacific Northwest (WA, OR, ID, MT), western Canada (BC, AB) and Alaska, and in a small disjunct population just north of Lake Superior (where it was probably introduced by humans in the past 100 years). It can grow with very little soil, as long as the area is wet. It grows in huge thickets, seen primarily in Alaska and northern British Columbia.

Native range: Devil's club grows in wet, rocky ravines or riparian habitats in the Pacific Northwest (WA, OR, ID, MT), western Canada (BC, AB) and Alaska, and in a small disjunct population just north of Lake Superior (where it was probably introduced by humans in the past 100 years). It can grow with very little soil, as long as the area is wet. It grows in huge thickets, seen primarily in Alaska and northern British Columbia.

Harvest, Cultivation, and Ecology

Cultivation: There is currently no significant cultivation of this plant practiced. If attempted it requires constantly moist soils, and does best in a forested habitat with dense shade. It does not tolerate drought well, but is quite frost resistant (except for young plants and young shoots). It can be transplanted and does tolerate pruning.

Extreme caution is warranted when harvesting or working with this plant, as the prickles can cause severe injuries, particularly to the eyes (Mader, et al. 2008). Goggles or other eye protection are recommended as a minimum; long sleeves, long pants, and thick gloves are also recommended when working with the plant to prevent puncture wounds.

Wildcrafting:

See the discussion above under Cultivation for the dangers of injury due to the plant's prickles, and steps needed to prevent them.

Ecological Status: Devil's club is not presently considered threatened, though habitat loss is a serious possible problem. The riparian areas where it thrives are also often coveted for development by humans. However, it grows in many highly inhospitable areas, particularly in northern British Columbia and southern Alaska, that are highly unlikely to be impacted this way and which will serve as reserves for this plant.

Extreme caution is warranted when harvesting or working with this plant, as the prickles can cause severe injuries, particularly to the eyes (Mader, et al. 2008). Goggles or other eye protection are recommended as a minimum; long sleeves, long pants, and thick gloves are also recommended when working with the plant to prevent puncture wounds.

Wildcrafting:

See the discussion above under Cultivation for the dangers of injury due to the plant's prickles, and steps needed to prevent them.

Ecological Status: Devil's club is not presently considered threatened, though habitat loss is a serious possible problem. The riparian areas where it thrives are also often coveted for development by humans. However, it grows in many highly inhospitable areas, particularly in northern British Columbia and southern Alaska, that are highly unlikely to be impacted this way and which will serve as reserves for this plant.

References

Baranov AI (1982) "Medicinal uses of ginseng and related plants in the Soviet Union: Recent trends in the Soviet literature" J Ethnopharmacol 6:339–53.

Calway T, Du GJ, Wang CZ, et al. (2012) "Chemical and pharmacological studies of Oplopanax horridus, a North American botanical" J Nat Med 66(2):249–56.

de Laguna F (1972) Under Mount St. Elias: History and Culture of the Yakutat Tlingit (Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, US Govt. Printing Office, Washington DC).

Gottesfeld LMJ, Anderson B (1998) "Gitksan traditional medicine: Herbs and healing" J Ethnobiol 8(1):13–33.

Graham RCB, Noble RL (1955) "Comparison of in vitro activity of various species of Lithospermum and other plants to inactivate gonadotrophin" Endocrinology 56:239–47.

Gunther E (1973) Ethnobotany of Western Washington (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

Huang WH, Shao L, Wang CZ, et al. (2014) "Anticancer activities of polyynes from the root bark of Oplopanax horridus and their acetylated derivatives" Molecules 19(5):6142–62.

Inui T, Wang Y, Deng S, et al. (2007) "Counter–current chromatography based analysis of synergy in an anti–tuberculosis ethnobotanical" J Chromatogr A 1151(1–2):211–5.

Johnson LM (1997) Health, wholeness and the land: Gitksan traditional plant use and healing. PhD dissertation], University of Anthropology, University of Alberta, Edmonton.

Kari PR (1977) Dena'ina K'et'una (Tanaina Plantlore) (Anchorage: Adult Literacy Lab).

Kobaisy M, Abramowski Z, Lermer L, et al. (1997) “Antimycobacterial polyynes of devil's club (Oplopanax horridus), a North American native medicinal plant” J Nat Prod 60(11):1210–3.

Lantz TC, Swerhun K, Turner NJ (2004) "Devil's club {Oplopanax horridus): An ethnobotanical review" HerbalGram 62:33–48.

Large RG, Brocklesby HN (1938) "A hypoglycaemic substance from the roots of the devil's club (Fatsia horrida)" Can Med Assoc J 39(1):32–5.

MacDermot JH (1949) "Food and medicinal plants used by the Indians of British Columbia" Can Med Assoc J 39:32–5

Mader TH, Werner RP, Chamberlain DG (2008) "Corneal perforation and delayed anterior chamber collapse from a devil's club thorn [sic]" Cornea 27(8):961–2.

McCutcheon AR, Roberts TE, Gibbons E, et al. (1995) "Antiviral screening of British Columbian medicinal plants" J Ethnopharmacol 49:101–10

McCutcheon AR, Stokes RW, Thorson LM, et al. (1997) "Anti–mycobacterial screening of British Columbian medicinal plants" Int J Pharmacognosy 35:77–83.

McGill CM, Alba-Rodriguez EJ, Li S, et al. (2014) "Extracts of devil's club (Oplopanax horridus) exert therapeutic efficacy in experimental models of acute myeloid leukemia" Phytother Res 28(9):1308–14.

Piccoli LJ, Spinapolice ME, Hecht M (1940) "A pharmacologic study of devil’s club root (Fatsia horrida)" J Am Pharm Assoc 29:11–12.

Stuhr ET, Henry FB (1944) "An investigation of the root bark of Fatsia horrida" Pharmaceutical Arch 15:9–15.

Tai J, Cheung S, Cheah S, et al. (2006) "In vitro anti–proliferative and antioxidant studies on devil's club Oplopanax horridus" J Ethnopharmacol 108(2):228–35.

Turner NC (1973) "The ethnobotany of the Bella Coola Indians of British Columbia" Syesis 6:193–220.

Turner NJ (1982) "Traditional use of devil's-club (Oplopanax horridus; Araliaceae) by native peoples in western North America" J Ethnobiol 2(1):17–38.

Turner NC, Bell MAM (1973) "The ethnobotany of the Southern Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia" Econ Botany 27(3):257–310.

Thommassen HV, Wilson RA, McIlwain RG (1990) “Effect of devil’s club on blood glucose levels in diabetes mellitus” Canadian Family Physician 36:62–5.

Vogel VJ (1970) American Indian Medicine (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press).

Wang CZ, Zhang Z, Huang WH, et al. (2013) "Identification of potential anticancer compounds from Oplopanax horridus" Phytomedicine 20(11):999–1006.

Wu K, Wang CZ, Yuan CS, Huang WH (2018) "Oplopanax horridus: Phytochemistry and pharmacological diversity and structure-activity relationship on anticancer effects" Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018:9186926.

Calway T, Du GJ, Wang CZ, et al. (2012) "Chemical and pharmacological studies of Oplopanax horridus, a North American botanical" J Nat Med 66(2):249–56.

de Laguna F (1972) Under Mount St. Elias: History and Culture of the Yakutat Tlingit (Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, US Govt. Printing Office, Washington DC).

Gottesfeld LMJ, Anderson B (1998) "Gitksan traditional medicine: Herbs and healing" J Ethnobiol 8(1):13–33.

Graham RCB, Noble RL (1955) "Comparison of in vitro activity of various species of Lithospermum and other plants to inactivate gonadotrophin" Endocrinology 56:239–47.

Gunther E (1973) Ethnobotany of Western Washington (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

Huang WH, Shao L, Wang CZ, et al. (2014) "Anticancer activities of polyynes from the root bark of Oplopanax horridus and their acetylated derivatives" Molecules 19(5):6142–62.

Inui T, Wang Y, Deng S, et al. (2007) "Counter–current chromatography based analysis of synergy in an anti–tuberculosis ethnobotanical" J Chromatogr A 1151(1–2):211–5.

Johnson LM (1997) Health, wholeness and the land: Gitksan traditional plant use and healing. PhD dissertation], University of Anthropology, University of Alberta, Edmonton.

Kari PR (1977) Dena'ina K'et'una (Tanaina Plantlore) (Anchorage: Adult Literacy Lab).

Kobaisy M, Abramowski Z, Lermer L, et al. (1997) “Antimycobacterial polyynes of devil's club (Oplopanax horridus), a North American native medicinal plant” J Nat Prod 60(11):1210–3.

Lantz TC, Swerhun K, Turner NJ (2004) "Devil's club {Oplopanax horridus): An ethnobotanical review" HerbalGram 62:33–48.

Large RG, Brocklesby HN (1938) "A hypoglycaemic substance from the roots of the devil's club (Fatsia horrida)" Can Med Assoc J 39(1):32–5.

MacDermot JH (1949) "Food and medicinal plants used by the Indians of British Columbia" Can Med Assoc J 39:32–5

Mader TH, Werner RP, Chamberlain DG (2008) "Corneal perforation and delayed anterior chamber collapse from a devil's club thorn [sic]" Cornea 27(8):961–2.

McCutcheon AR, Roberts TE, Gibbons E, et al. (1995) "Antiviral screening of British Columbian medicinal plants" J Ethnopharmacol 49:101–10

McCutcheon AR, Stokes RW, Thorson LM, et al. (1997) "Anti–mycobacterial screening of British Columbian medicinal plants" Int J Pharmacognosy 35:77–83.

McGill CM, Alba-Rodriguez EJ, Li S, et al. (2014) "Extracts of devil's club (Oplopanax horridus) exert therapeutic efficacy in experimental models of acute myeloid leukemia" Phytother Res 28(9):1308–14.

Piccoli LJ, Spinapolice ME, Hecht M (1940) "A pharmacologic study of devil’s club root (Fatsia horrida)" J Am Pharm Assoc 29:11–12.

Stuhr ET, Henry FB (1944) "An investigation of the root bark of Fatsia horrida" Pharmaceutical Arch 15:9–15.

Tai J, Cheung S, Cheah S, et al. (2006) "In vitro anti–proliferative and antioxidant studies on devil's club Oplopanax horridus" J Ethnopharmacol 108(2):228–35.

Turner NC (1973) "The ethnobotany of the Bella Coola Indians of British Columbia" Syesis 6:193–220.

Turner NJ (1982) "Traditional use of devil's-club (Oplopanax horridus; Araliaceae) by native peoples in western North America" J Ethnobiol 2(1):17–38.

Turner NC, Bell MAM (1973) "The ethnobotany of the Southern Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia" Econ Botany 27(3):257–310.

Thommassen HV, Wilson RA, McIlwain RG (1990) “Effect of devil’s club on blood glucose levels in diabetes mellitus” Canadian Family Physician 36:62–5.

Vogel VJ (1970) American Indian Medicine (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press).

Wang CZ, Zhang Z, Huang WH, et al. (2013) "Identification of potential anticancer compounds from Oplopanax horridus" Phytomedicine 20(11):999–1006.

Wu K, Wang CZ, Yuan CS, Huang WH (2018) "Oplopanax horridus: Phytochemistry and pharmacological diversity and structure-activity relationship on anticancer effects" Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018:9186926.